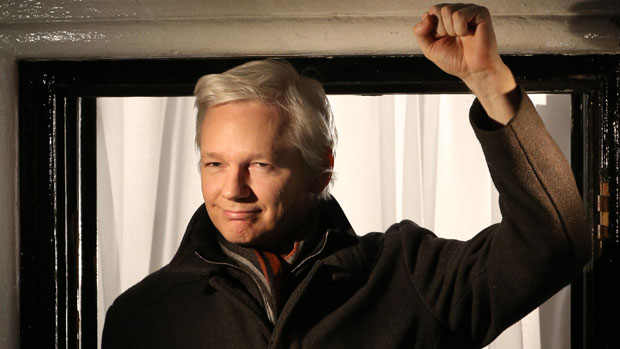

How WikiLeaks’ Julian Assange lost his moral authority

In Depth: Ecuador’s president says exiled cyber rebel is ‘more than a nuisance’

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Barack Obama championed government whistle-blowers during his presidential campaign, saying they were “part of a healthy democracy” that “must be protected from reprisal”.

Yet during his time in office, Obama prosecuted eight whistle-blowers - more than twice the total number under all previous US presidents, says The Guardian.

Unfortunately for Julian Assange, his self-imposed exile in Ecuador’s London embassy coincided with Obama’s second term in office. The WikiLeaks founder has since spent more than five years holed up there. Although Assange is no longer wanted by Swedish prosecutors, to face a rape charge, the UK has threatened to arrest him for skipping bail. In the long term, Assange fears he may be extradited to the US for questioning over the activities of WikiLeaks.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

“When I started writing about whistle-blowers a few years ago, there was genuine sympathy for whistle-blowers across international public opinion, and one sensed a common feeling of indignation at the repression whistle-blowers suffered,” writes sociologist Geoffroy de Lagasnerie on Open Democracy, an independent media platform that focuses on human rights. “But during the last few months, something seems to have changed. There now seems to be a real mistrust – if not outright hostility – with regard to Assange.”

So what changed?

The currency of democratic freedom

Back in 2010, “at the height of WikiLeaks’ fame - or infamy - the Left claimed Assange as one of their own”, says The Times’s David Aaronovitch.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Assange and his website seemed to be building a world of transparency in which government and corporations would be held accountable.

“Transparency and information, to paraphrase Thomas Jefferson, are the ‘currency’ of democratic freedom,” John Pilger wrote in the New Statesman in 2012, shortly after Assange entered the embassy.

What has caused the shift in opinion?

The reputation of Assange and WikiLeaks has been damaged by several incidents. In 2011, the Australian-born computer hacker, once lauded for exposing the dark secrets of international diplomacy, was pilloried by the mainstream media in 2011 for publishing raw classified data - with no attempt to protect the innocent, The Independent says.

WikiLeaks released more than 251,000 US diplomatic cables into the public domain. According to the newspaper: “At least 150 of the documents refer to whistle-blowers, and thousands include the names of sources that the US believed could be put in danger by the publication of their identities.”

The leak was condemned in a joint statement by The Guardian, The New York Times, Spanish newspaper El Pais, Germany’s Der Spiegel and French paper Le Monde that said: “Our previous dealings with WikiLeaks were on the clear basis we would only publish cables which had been subjected to a thorough joint editing and clearance process.”

Despite this blow to the WikiLeaks team, however, “nothing seems to have been more damaging for their reputation than the 2016 US presidential election campaign”, de Lagasnerie writes.

The site’s publication of leaked Democratic National Committee emails fuelled the perception that Assange had become a neoconservative, cosying up with the political circles of Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin, de Lagasnerie adds.

Assange also appears to have found an unlikely supporter in the shape of former UKIP leader Nigel Farage - also a friend to Trump - who, when intercepted as he emerged from the Ecuadorian embassy in March 2017, told Buzzfeed that he “couldn’t remember” what he’d been doing inside for the previous 40 minutes.

What’s in a name?

“US officials who once dismissed WikiLeaks as a little more than an irritating propaganda machine, and Assange as an anti-establishment carnival barker, now take a far darker view of the group,” The Washington Post reports.

CIA Director Mike Pompeo said in May 2017 that his colleagues found praise for WikiLeaks “perplexing and deeply troubling”.

“As long as they make a splash, they care nothing about the lives they put at risk or the damage they cause to national security,” Pompeo said, according to CNN. “It’s time to call out WikiLeaks for what it really is: a non-state hostile intelligence service often abetted by state actors, like Russia.”

Pompeo later doubled down on that assessment, describing WikiLeaks as a national security threat and comparing its work to that of Hezbollah, Islamic State and al-Qa’eda.

But is WikiLeaks a hostile intelligence group, or simply a media organisation?

The distinction could be important should the US try to extradite Assange from Britain. A UK information tribunal last year recognised WikiLeaks as a media organisation, which could allow Assange to argue against US extradition on grounds of press freedom.

Pure chaos

Another reason WikiLeaks may have lost its way is the chaotic nature of its own working processes.

“There aren’t any systems. There aren’t any procedures - no formal roles, no working hours. It’s all just Julian and whatever he feels like,” one former WikiLeaks activist told The Washington Post.

The “size of WikiLeaks’ staff and its finances are also murky”, adds the newspaper. WikiLeaks has “amassed a stash of bitcoin, a digital currency that enables anonymous, bank-free transactions”.

The group is believed to have a stockpile of bitcoin worth a total of around $25m, although the volatility of the cybercurrency means that figure may fluctuate wildly.

‘An inherited problem’

Ecuadorian President Lenin Moreno this week referred to Assange as an “inherited problem” that dates back to June 2012, when the cyber rebel claimed political asylum in Ecuador’s embassy.

Moreno said in a television interview that Assange had created “more than a nuisance” for his government.

It is not the first time Moreno has aired his misgivings. Following Assange’s public support for the independence campaign in Catalonia, Moreno warned Assange not to interfere in either Ecuadorian politics or “that of nations that are our friends”.

According to El Pais, an influential tweet about the referendum posted by Assange went viral as a result of activity on fake social media accounts.

The newspaper also claimed that Russian news outlet RT used its Spanish-language portal “to spread stories on the Catalan crisis with a bias against constitutional legality”.

Nihilistic opportunism?

Hillary Clinton has described the WikiLeaks founder as “a kind of nihilistic opportunist who does the bidding of a dictator” - a reference to Russian President Vladimir Putin, according to The Daily Telegraph.

But Assange retains the support of some commentators, who see him as a martyr to a noble cause.

“Assange is one of those rare contemporary political figures to adopt a truly global perception of the world,” says de Lagasnerie.

“Someone once told me that if Edward Snowden enjoys greater sympathy than Assange in Western Europe or the United States, it’s because Snowden’s leaks involved predominantly white Westerners, while much of the information WikiLeaks publishes involves Yemenites, Afghans, or Iraqis. I think there is much truth to this.”

-

Political cartoons for February 18

Political cartoons for February 18Cartoons Wednesday’s political cartoons include the DOW, human replacement, and more

-

The best music tours to book in 2026

The best music tours to book in 2026The Week Recommends Must-see live shows to catch this year from Lily Allen to Florence + The Machine

-

Gisèle Pelicot’s ‘extraordinarily courageous’ memoir is a ‘compelling’ read

Gisèle Pelicot’s ‘extraordinarily courageous’ memoir is a ‘compelling’ readIn the Spotlight A Hymn to Life is a ‘riveting’ account of Pelicot’s ordeal and a ‘rousing feminist manifesto’

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military