American indifference to Cuba is the end of an era

So closes an expansive vision of American foreign policy that extends back to 1898

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Suppose they gave a revolution and nobody cared.

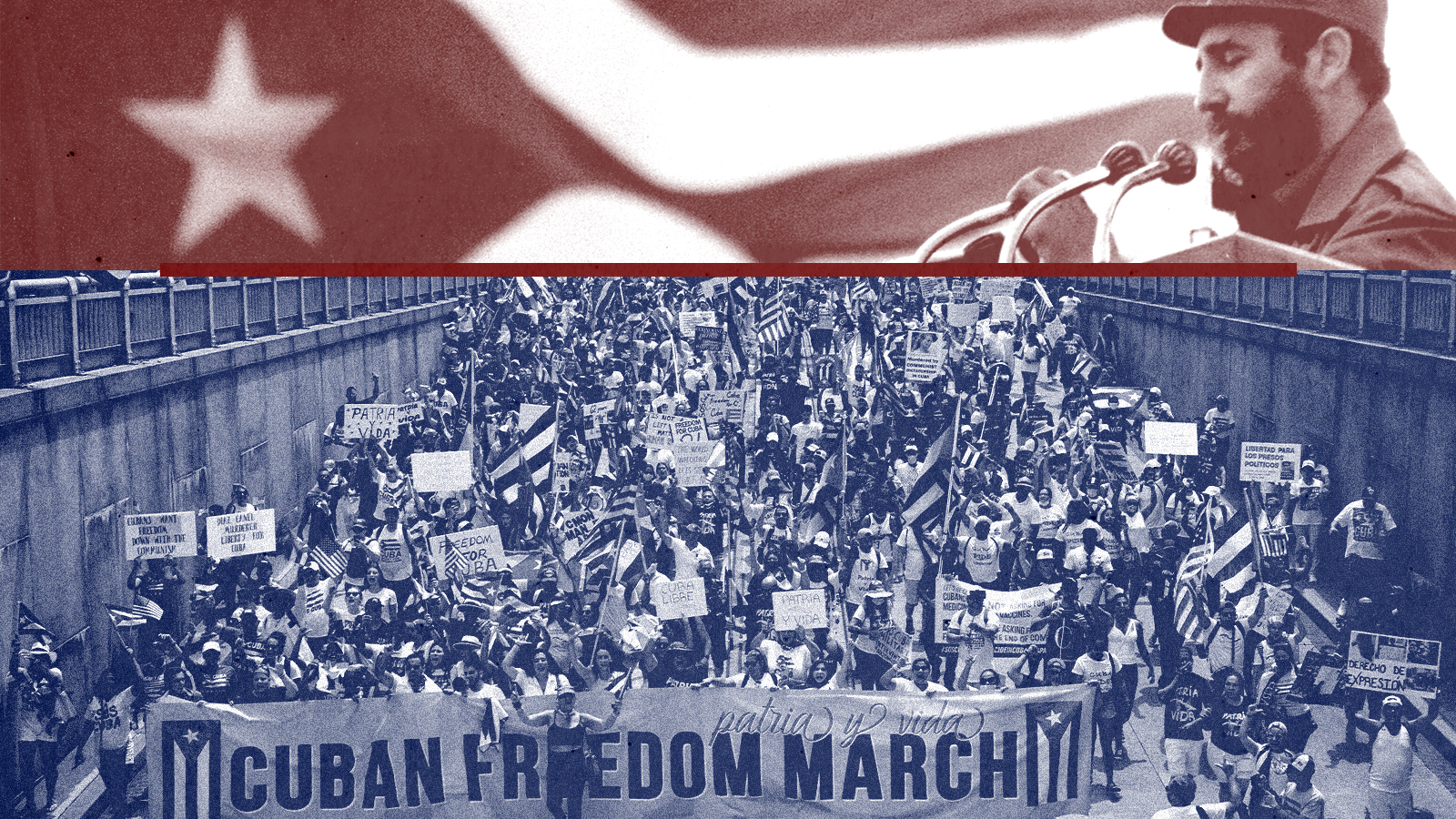

Just two weeks ago, thousands of Cubans joined the largest public protests in decades. Beginning in one city and focusing on economic concerns, demonstrations spread across the country and turned against the government itself. "Libertad! Libertad!" chanted protestors. Despite this inspiring beginning, the nascent movement has entered the crackdown phase. Hundreds of dissidents are being detained. Many others are subject to heightened surveillance.

Since the failure of the Bay of Pigs operation, many Americans have dreamed of freeing Cuba from Communist rule. So it's striking how muted the U.S. reaction has been. Beyond issuing a bland statement, the White House response was to impose sanctions on a single official. Perhaps that's all that could be expected of a Democrat who lost Florida.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Cuban-American activists tried to raise the temperature with rallies in Miami, Los Angeles, and Washington. Even so, congressional Republicans are politely avoiding the issue. And conservative media have treated recent developments as a humanitarian story rather than a political rallying cry.

That's partly the result of generational shifts. After decades of Communist rule, the public has accepted the status quo on the island. Polls have found majority support for normalizing relations going back to the 1970s. Some Americans recall the 1959 revolution, while the Mariel boatlift is closer to recent memory. But the median American was born in 1983. For most of us, these events are ancient history.

Without the military backing of a superpower, Cuban communism lost its ability to frighten anyone — and may have become more appealing to a certain audience. The mirage of a beach party with socialist characteristics is irresistible to highly educated leftists. But even those less likely to wear Che Guevara t-shirts seem willing to accept Cuba's reversion to its pre-revolutionary status as a tourist destination. About half of the public now express generally favorable opinions about an island known for its cigars, rum, and music more than its ideology.

Above all, though, indifference to protests in Cuba reflects a transformation of our expectations for foreign policy. After debacles in the Middle East, there is little appetite among elected officials or the general public for foreign intervention in support of liberty, democracy, or other grand principles. Twenty years ago, the possibility of a second Cuban revolution would have provoked immediate debate about material and logistical support for the resistance — perhaps even military action. So far, it's been greeted with a shrug.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

That suggests the end of an era that extends beyond 9/11 and the Bush Doctrine. It's even longer than the so-called "American Century" that began with the Second World War. The vision of America as the armed guardian of freedom around the world goes all the way back to the Spanish-American War of 1898, when the United States engaged in its first conflict on overseas territory (naval battles don't count). Ironically, the goal of that war was to assist Cuban rebels in securing independence.

The decline of this expansive vision is on the whole a good thing. That's partly because its results have been mixed. The United States helped liberate Europe from Nazi and Communist oppression and rebuild from the wreckage. In Asia and Latin America, however, our efforts were more brutal, destabilizing, and intrusive. In addition to their cost in lives and dignity, they may also have been counterproductive in strategic terms. The Iraq War is only the latest example of how the unwise assertion of American power can actually reduce it.

A moralized and globalized understanding of America's role also has domestic consequences. Encouraged to view the rest of the world as the site of ideological struggle, we learned to interpret our own affairs in the same terms. At least since the Cold War, unavoidable tradeoffs tend to be treated as existential disputes. Ronald Reagan attracted both admiration and denunciation for his characterization of Medicare as a fatal step toward tyranny — a rhetorical move that continues to influence our debates about healthcare. It was not so widely known that he supported an alternative program that would have provided care to the elderly poor using different means.

Supporters of a more expansive foreign policy sometimes argue that we can't defend freedom at home unless we fight tyranny abroad. Until the turn of the 20th Century, though, most of our leading statesmen took the opposite view. According to historian Walter McDougall, the dominant opinion in this period was that "America would be defined not by anything its government did abroad but by what it was supposed to be at home." Even Jefferson, the most idealistic of the founders, concluded that "I cordially wish well to the progress of liberty in all nations, and would forever give it the weight of our countenance, yet they are not to be touched without contamination from their other bad principles."

America's contacts with the rest of the world have increased vastly since the 18th Century. And the United States never observed Jefferson's dictum consistently, particularly in the Americas and maybe especially in regard to Cuba. Even so, a combination of good wishes and practical restraint is the right response to the Cuban situation today. We should still hope for Cuba Libre. But we shouldn't get involved.

Samuel Goldman is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate professor of political science at George Washington University, where he is executive director of the John L. Loeb, Jr. Institute for Religious Freedom and director of the Politics & Values Program. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard and was a postdoctoral fellow in Religion, Ethics, & Politics at Princeton University. His books include God's Country: Christian Zionism in America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018) and After Nationalism (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021). In addition to academic research, Goldman's writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and many other publications.