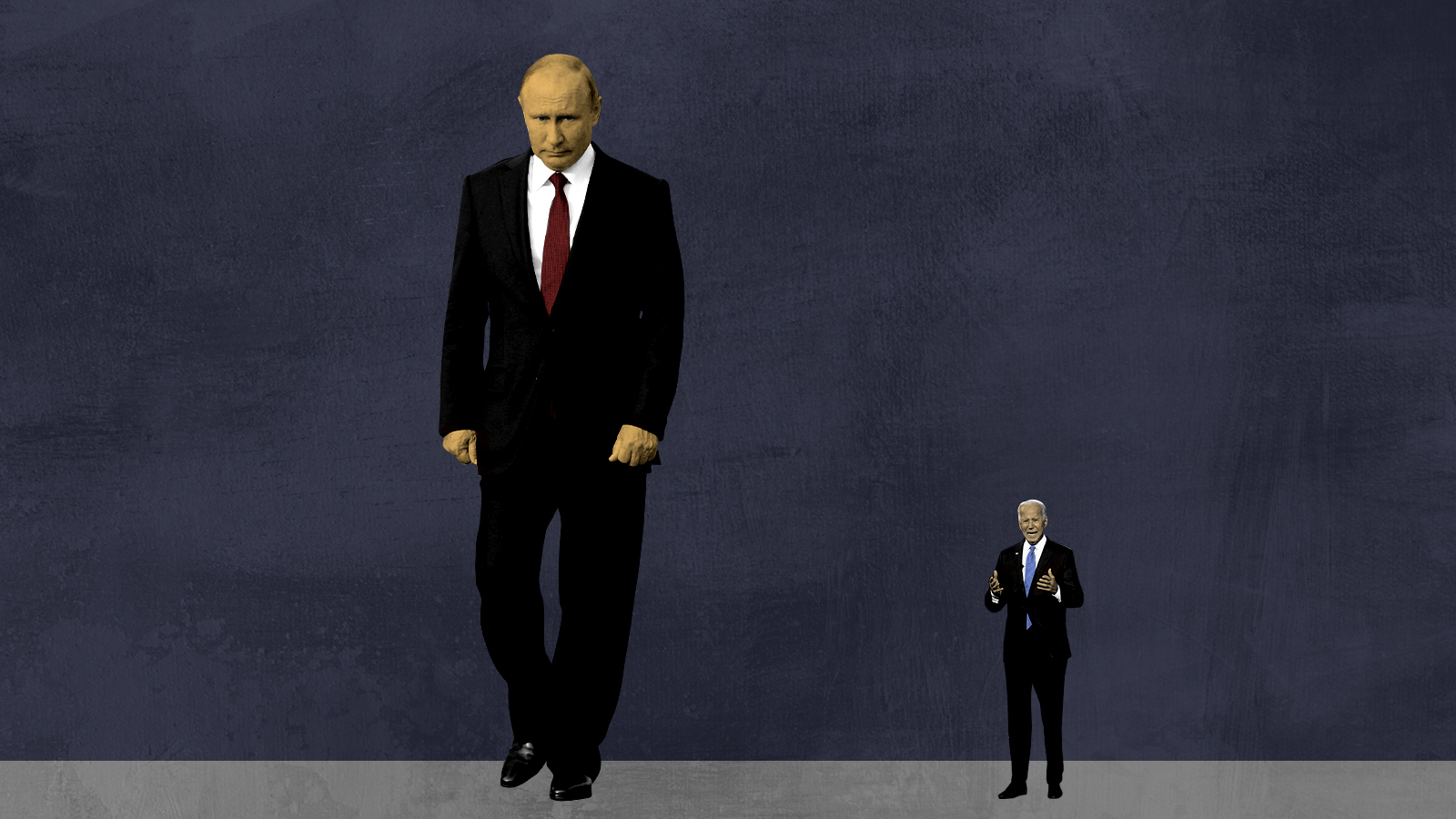

As Russia expands into Ukraine, the U.S. shrinks from the world's stage

The U.S. is neither feared nor loved enough to protect Ukraine from Russia

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Vladimir Putin and Russia have ended the Pax Americana by calling what turned out to be America's bluff.

The proof? Russian tanks are moving deeper into Ukraine.

With the end of the Cold War, the United States promised everyone everything, extending its protection as far east as tiny Lithuania. Sure, little buddy, if that bully Russia ever pulls itself off the canvas, we've got your back… But the U.S. reached out too far, promised too much, and now the bluff is called: The embers of imperial ambition can't protect poor, friendly Ukraine.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Once considered the Soviet heartland and breadbasket — at least by the Russians — Ukraine has admittedly played coy over the years. At times, it has leaned West; other times, toward Moscow. Recently, it's been looking for a bit more democracy (and certainly the greater wealth) that comes from cozying up to Western Europe and the United States. While Kyiv hadn't formally asked to join NATO — and NATO hasn't offered — friendly allyship, if not formal alliance, and full integration into Europe were certainly on the table. And Ukraine knows the United States and NATO protect their friends — or at least their aura of resolve does.

But now that glow has faded, and as Winston Churchill said, the lights are going out. A major land war has once again grabbed Europe by the throat.

For more than 70 years, the United States, through the power of its ideals and ideas — and the threat of overwhelming force — has helped keep the world relatively peaceful and the map's borders largely in place. When you speak about relative peace, unfortunately, you have to compare the years since World War II with all of human history before it. People are still murderous, but far less so than they have ever been. Ministers of war have become defense ministers all over the world. Euphemism? To a certain extent, yes, but also a demonstration of a change in attitudes about the normality of war.

We believe peace to be the norm, and wars to be a breach of that peace. Our recent ancestors, on the other hand, saw war as an unfortunate norm and peace to be a nice break. This fundamental change came in the wake of the world's bloodiest war so far, World War II, when Germans and Soviets killed each other at a rate that now is simply unimaginable. Not figurative tens of millions: literal tens of millions. Civilian deaths were also in the tens of millions around the world, including the intricately organized slaughter of the Holocaust, which killed two-thirds of the Jews in Europe. All told, 3 percent of the world died in that one war, culminating with the threat of complete oblivion that became real with the clouds over Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The victors divided Europe at Yalta and set up an economic blueprint for the world at Bretton Woods with gold and the U.S. dollar as kings. There were new rules for conducting war and peace, largely guaranteed by the United States and its allies, with the Soviet Union setting up a mirror system of its own. The rules were bent over and over again, with horrible proxy wars in Korea, Vietnam, across Africa and Latin America. Even genocide — a concept without a word before the war — has continued, in Cambodia, in China, in Myanmar.

But the Cold War was labeled such because the world remembered what a hot war was like, and this wasn't it.

The United States wanted to impose imperfect democracy and McDonald's across the globe, and became rich doing so. The Soviets wanted to change human nature and create the "New Soviet Man." But the USSR eventually became so riddled with corruption that it could no longer stand — and in 1989, the United States was there to collect all the pieces.

By the time the Soviet Union formally dissolved in 1991, the U.S. stood alone with its empire of influence that reached from Russia's doorstep all the way into China's home waters. Empire brings incredible rewards, including cheap gas and other imports, rising living standards, and a defense perimeter that stretches literally thousands of miles from the homeland. It also brings hubris and a sense of absolute power.

Discord at home, disinterest in the world abroad, and fatigue from unwinnable wars has changed that. Americans seem to feel the empire is already lost, and a need to retrench. The world is tired of the American act. And sometimes all it takes to start a war is a lack of resolve on the part of the defender.

America's bluff has been called. Now the only thing that is certain is a world less stable than it has been for nearly 80 years and the inevitable carnage that will follow.

Jason Fields is a writer, editor, podcaster, and photographer who has worked at Reuters, The New York Times, The Associated Press, and The Washington Post. He hosts the Angry Planet podcast and is the author of the historical mystery "Death in Twilight."

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

Putin’s shadow war

Putin’s shadow warFeature The Kremlin is waging a campaign of sabotage and subversion against Ukraine’s allies in the West

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

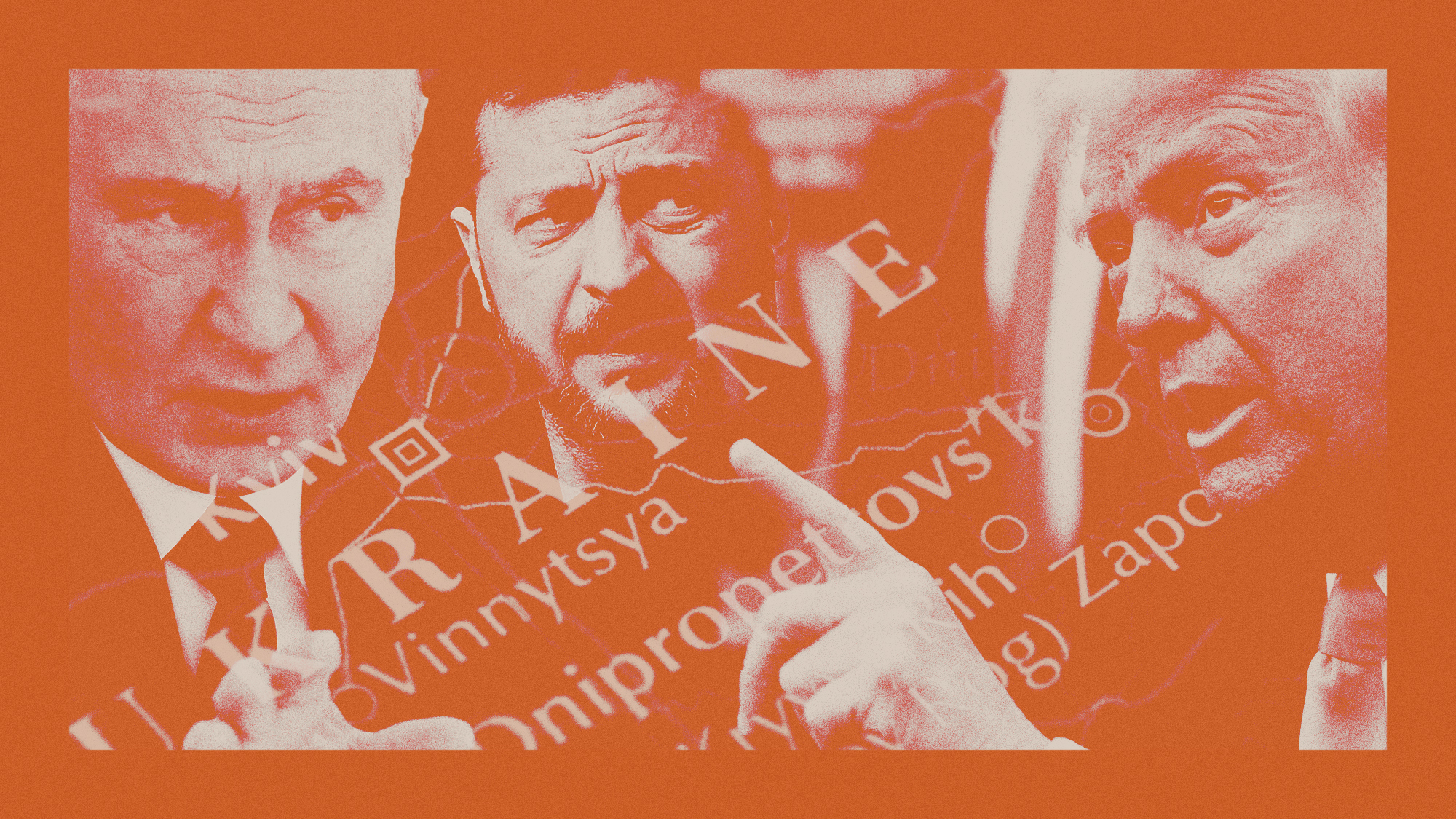

Ukraine, US and Russia: do rare trilateral talks mean peace is possible?

Ukraine, US and Russia: do rare trilateral talks mean peace is possible?Rush to meet signals potential agreement but scepticism of Russian motives remain

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

The rise of the spymaster: a ‘tectonic shift’ in Ukraine’s politics

The rise of the spymaster: a ‘tectonic shift’ in Ukraine’s politicsIn the Spotlight President Zelenskyy’s new chief of staff, former head of military intelligence Kyrylo Budanov, is widely viewed as a potential successor