'Rape can't cause pregnancy': A brief history of Todd Akin's bogus theory

The embattled Akin believed (at least until 48 hours ago) that women can't get pregnant from rape. As bizarre as that theory is, he's hardly the first to spout it

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Rep. Todd Akin (R-Mo.), the Republican challenger to Sen. Claire McCaskill (D-Mo.), is fighting for his political life after the broadcast Sunday of a local TV interview in which he said that "legitimate rape" rarely, if ever, results in pregnancy. But his misguided belief that rape victims don't get pregnant is hardly a new idea — in fact, it's "reproductive biology from scholarship dating back to King John and Magna Carta," says Dan Turner at the Los Angeles Times, when doctors would "wear cowls on their heads and spend most of their time swirling urine samples around in a flask in search of black bile and other ill humors." And Akin is hardly the only anti-abortion politician who has passed such an idea off as medical fact. Here's a look back at where the belief comes from, and why it's still around:

How long has this no-pregnancy-in-rape theory been around?

"The idea that rape victims cannot get pregnant has long roots," says Vanessa Heggie at Britain's The Guardian. Think 13th century. One of the earliest British legal texts — Fleta, from about 1290 — has this familiar-sounding clause: "If, however, the woman should have conceived at the time alleged in the appeal, it abates, for without a woman's consent she could not conceive." Samuel Farr's Elements of Medical Jurisprudence, a treatise from 1785 (second edition 1814), elaborates: "For without an excitation of lust, or the enjoyment of pleasure in the venereal act, no conception can probably take place. So that if an absolute rape were to be perpetrated, it is not likely she would become pregnant."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What's the medical underpinning of this theory?

From medieval times until the 19th century, doctors and laypeople alike widely believed that women only conceived if they had an orgasm, since the presumed female "seed" — needed to complement the male sperm to achieve pregnancy — was thought be secreted only during sexual climax. "By logical extension, then," says Heggie, "if a woman became pregnant, she must have experienced orgasm, and therefore could not have been the victim of an 'absolute rape'."

When did it get tied into abortion politics?

In 1980, lawyer James Leon Holmes (now a federal judge in Arkansas) argued for a constitutional ban on abortion with this colorful analogy: "Concern for rape victims is a red herring because conceptions from rape occur with approximately the same frequency as snowfall in Miami." A series of state lawmakers have made similar arguments since at least 1988, when Pennsylvania state Rep. Stephen Freind (R) argued in a debate on abortion that the odds of pregnancy from rape are "one in millions and millions and millions," because "when that traumatic experience is undergone, a woman secretes a certain secretion which has a tendency to kill the sperm."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Is that the more modern biological explanation?

Not necessarily the "secretions" part, but "the idea that trauma is a form of birth control continues to be promulgated by anti-abortion forces that seek to outlaw all abortions, even in cases of rape or incest," says Garance Franke-Ruta at The Atlantic. Some lawmakers have been kind of fuzzy on the specifics — Akin was, and North Carolina state Rep. Henry Aldridge (R) was more colorfully vague in 1995, when he said "medical authorities agree" that "people who are raped — who are truly raped — the juices don't flow, the body functions don't work, and they don't get pregnant." But non-politician John C. Willke, a physician and former president of the National Right to Life Committee, lays out his case fairly clearly in a 1999 article in Life Issues Connector, which is still reprinted on anti-abortion websites: "To get and stay pregnant a woman's body must produce a very sophisticated mix of hormones," and the terrible trauma of "assault rape" can upset that hormone cocktail and "radically upset her possibility of ovulation, fertilization, implantation, and even nurturing of a pregnancy."

Is there any scientific basis for this belief?

No. It's the "contemporary equivalent of the early American belief that only witches float," says Franke-Ruta. The idea that rape would make a woman "physiologically more likely to miscarry (or not to conceive at all)" might sound sort of plausible "from a holistic perspective," says James Hamblin at The Atlantic. After all, we spend millions of dollars on "foods, colors, aromas, feng shui" and other purported tools for "optimizing an environment for conception." But the theory "doesn't hold, to any relevant degree." A widely cited 1996 study in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology found that each instance of rape has a 5 percent chance of resulting in pregnancy, a figure that "includes rapes in which condoms were used." Other studies from foreign countries have reported much higher percentages. In real terms, the AJOG study found, more than 32,000 pregnancies result from rape each year in the U.S. alone.

Is there any upside to claiming that rape can't result in pregnancy?

No. The politics are terrible, says Michelle Goldberg at The Daily Beast. It's telling that Republicans are running away from Akin as fast as they can — obviously most Americans don't agree that "women possess magical mechanisms for preventing conception when they've been attacked." But the problem isn't the idea — "banning abortion for rape victims used to be an outré position among Republicans, now it's become almost normative" — it's that Akin and his fellow conservatives have trouble explaining their "absolutist anti-abortion politics to the general public." Just last year, House Republicans had to drop a high-profile amendment, cosponsored by Akin and GOP vice presidential hopeful Rep. Paul Ryan (R-Wis.), to exempt only "forcible rape," not all rape, from a federal ban on abortion funding.

So why do Akin and his allies keep making this argument?

They have to try: To justify a ban on all abortions, politically speaking, rape "needs to be defined differently," says The Atlantic's Franke-Ruta. Whether its "legitimate" or "forcible" or "assault rape," it must be sold as "something that does not result in pregnancy." Besides, the argument doesn't look so ridiculous inside "the bubble around which the far right has wrapped themselves," says David Dayen at Firedoglake. If you truly believe "that the good Lord intelligently designed women to activate a pregnancy blocker in a time of trauma," you can avoid some tough moral questions. The moral logic of the absolutists' side is "tighter than the logic that leads the pro-life majority to favor the rape, incest, and life-of-the-mother exceptions," says David Frum at The Daily Beast. If you believe that "a pregnancy becomes a full human person at the very instant of conception," as much of the GOP does, then any exemption from an abortion ban amounts to murder. "These views may be shocking, but they are not stupid."

Sources: The Atlantic (2), BuzzFeed, The Daily Beast (2), Firedoglake, The Guardian, The Los Angeles Times, Philadelphia Daily News, Talking Points Memo, The Washington Post

-

Trump’s EPA kills legal basis for federal climate policy

Trump’s EPA kills legal basis for federal climate policySpeed Read The government’s authority to regulate several planet-warming pollutants has been repealed

-

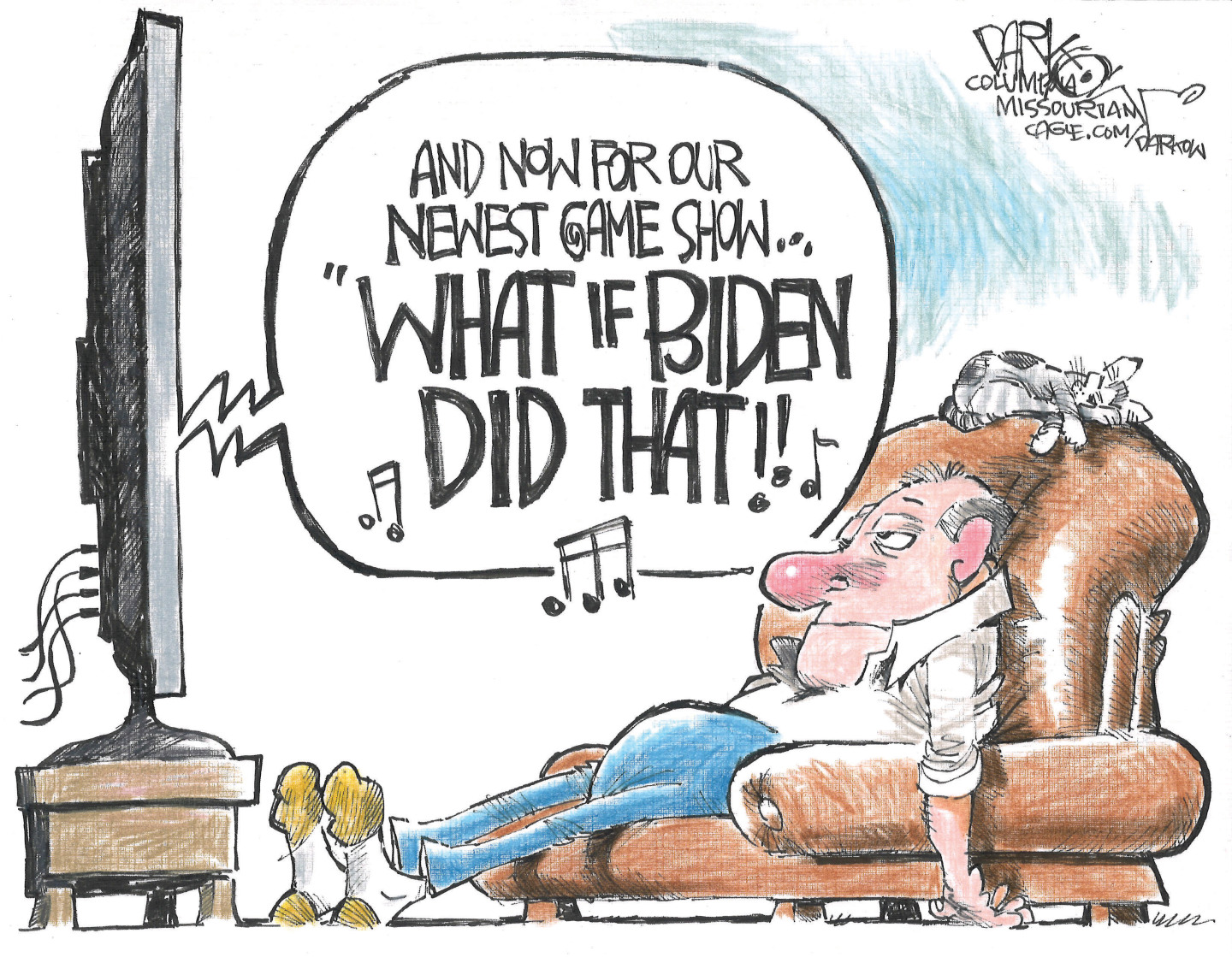

Political cartoons for February 13

Political cartoons for February 13Cartoons Friday's political cartoons include rank hypocrisy, name-dropping Trump, and EPA repeals

-

Palantir's growing influence in the British state

Palantir's growing influence in the British stateThe Explainer Despite winning a £240m MoD contract, the tech company’s links to Peter Mandelson and the UK’s over-reliance on US tech have caused widespread concern

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred