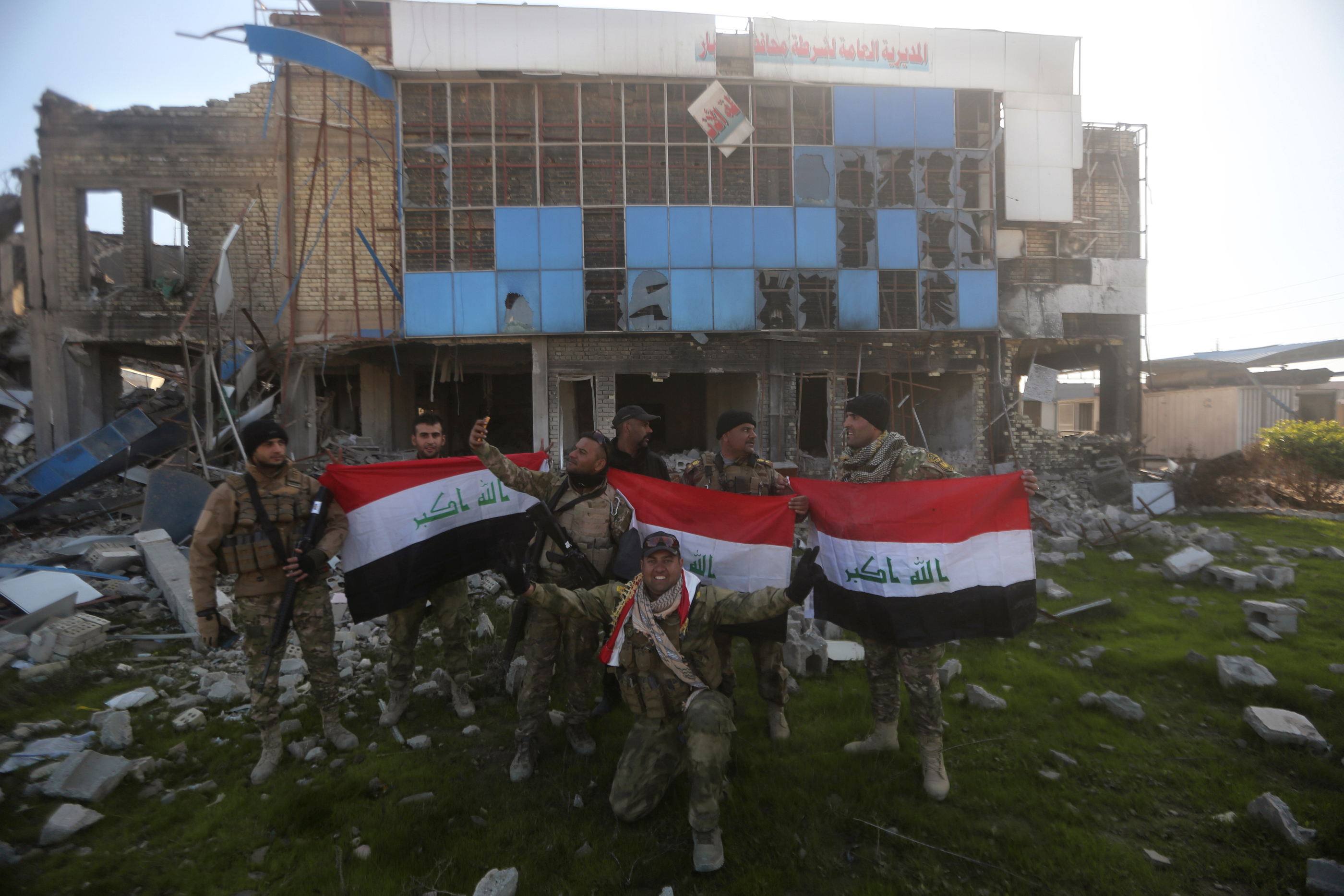

Obama's gamble in Iraq pays off

U.S. pressure pushed al-Maliki to resign

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The president carries himself weakly. His words don't pressure anyone. American foreign policy is impotent. Nouri al-Maliki, endorsed by the previous administration to run Iraq, would never resign. In fact, he'll dig in his heels precisely because Obama wanted him to go. He'll hold on to his power illegally.

Don't Do Stupid Stuff may be a shrunken encapsulation of President Obama's fundamental caution about the knee-jerk exercise of American military power, but it does not mean he shies away from risk. Intervening in Iraq is risky. Openly calling for Maliki to step down and then using what little actual leverage the United States has to assist (nonmilitary) forces that usher him out of power — that's risky, especially given that Iraq is in the middle of combusting, and a political system in transition, during war, does not inspire the confidence of anyone.

In front of the curtain, Secretary of State John Kerry repeatedly said Iraq's constitutional process was the only credible way for a new prime minister to be chosen. Behind the curtain, Vice President Joe Biden played hardball, giving Maliki a choice between deposing himself or allowing Baghdad to fall into chaos. Most certainly, there were threats to cut off support, and I'm sure The New York Times or another well-sourced entity will have a detailed tick-tock for us in the next few days.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Behind the scenes, the administration worked with Maliki's party, the Iraqi National Group, offering assurances that the U.S. would stand fully behind its chosen candidate, so long as it wasn't Maliki. The West encouraged Iraqi President Fouad Massoum to call for new elections within 30 days.

When people say that only a political solution will help Iraq, they mean two things. One: a strong leader who can unite the country without alienating a majority of a strong minority. Two: a political system that works, even minimally, and isn't seen as unfair. Finding a strong charismatic leader is probably impossible, because Iraq has not lived peacefully without the strong arm of a dictator. It is a state that was drawn, not a state that drew itself.

But the second is actually possible: Iraqis of all persuasions and demographic demarcations (Christians, Sunnis, Shiias, moderates, conservatives, agnostics, Baathists, and Kurds) need to have some confidence that they can participate in politics. Participating in politics creates a political culture, and a political culture forms bonds among even the most hated of rivals.

The U.S. invasion of Iraq plunged the country into chaos; the evisceration of the entire political apparatus after the war put a stop to any natural political realignment; the de-Baathification of the new government robbed it of its technocratic expertise, and the current administration's relative inattention to Maliki's turn toward sectarian warlordism after 2009 gave the current prime minister confidence that he could violate the boundaries of acceptable behavior. So that's on Obama, to some degree. The best thing the U.S. could do, without being stupid, is to try.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Iraq may not be closer to stability today than it was yesterday; the Iraqi National Group does not have a majority in parliament, so the unknown unknowns are pretty daunting. The Army is loyal to who knows whom. ISIS poses an existential threat to Iraq, the Middle East, and perhaps even to the United States.

But Maliki resigned within the framework of the current political system. That's a step toward legitimacy. Credit many (including Maliki's presumed patron, Iran), but apportion some of it to this administration.

Marc Ambinder is TheWeek.com's editor-at-large. He is the author, with D.B. Grady, of The Command and Deep State: Inside the Government Secrecy Industry. Marc is also a contributing editor for The Atlantic and GQ. Formerly, he served as White House correspondent for National Journal, chief political consultant for CBS News, and politics editor at The Atlantic. Marc is a 2001 graduate of Harvard. He is married to Michael Park, a corporate strategy consultant, and lives in Los Angeles.

-

Political cartoons for February 19

Political cartoons for February 19Cartoons Thursday’s political cartoons include a suspicious package, a piece of the cake, and more

-

The Gallivant: style and charm steps from Camber Sands

The Gallivant: style and charm steps from Camber SandsThe Week Recommends Nestled behind the dunes, this luxury hotel is a great place to hunker down and get cosy

-

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in Iraq

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in IraqThe Week Recommends Charming debut from Hasan Hadi is filled with ‘vivid characters’

-

The recycling crisis

The recycling crisisThe Explainer Much of the stuff Americans think they are "recycling" now ends up in landfills and incinerators. Why?

-

The L.A. teachers strike, explained

The L.A. teachers strike, explainedThe Explainer Everything you need to know about the education crisis roiling the Los Angeles Unified School District

-

The NSA knew about cellphone surveillance around the White House 6 years ago

The NSA knew about cellphone surveillance around the White House 6 years agoThe Explainer Here's what they did about it

-

America's homelessness crisis

America's homelessness crisisThe Explainer The number of homeless people in the U.S. is rising for the first time in years. What’s behind the increase?

-

The truth about America's illegal immigrants

The truth about America's illegal immigrantsThe Explainer America's illegal immigration controversy, explained

-

Chicago in crisis

Chicago in crisisThe Explainer The "City of the Big Shoulders" is buckling under the weight of major racial, political, and economic burdens. Here's everything you need to know.

-

The bad news about ISIS's defeat in Ramadi

The bad news about ISIS's defeat in RamadiThe Explainer The contours of a broader sectarian war are coming into focus

-

America can still destroy the world

America can still destroy the worldThe Explainer The decline of U.S. military power has been greatly exaggerated