Why the Supreme Court is allowing Texas to hold an unconstitutional election

Once again, the high court has joined with conservative state lawmakers to restrict minority voting

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

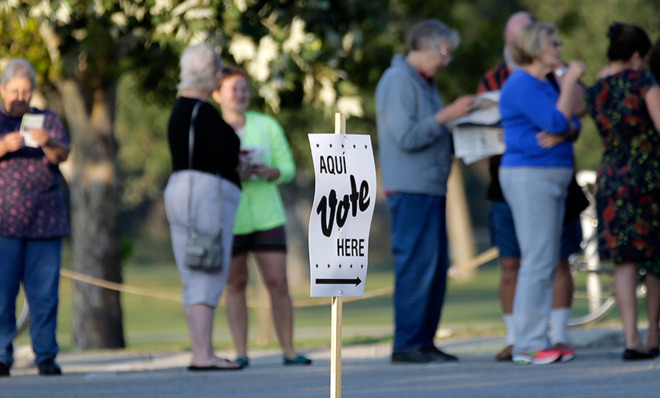

This weekend, the Supreme Court allowed Texas to apply new, stringent voting restrictions to the upcoming midterm elections, which could potentially disenfranchise hundreds of thousands of voters lacking proper identification. As Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg explained in a short but brilliant dissent, this is a disaster for the citizens of Texas: the upcoming elections will be conducted under a statute that is unconstitutional on multiple levels.

How could this happen?

There is, admittedly, a quasi-defensible reason for the court's latest move. The Supreme Court is usually reluctant to issue opinions that would change election rules when a vote is imminent. For example, the court recently acted to prevent Wisconsin from using its new voter ID law in the upcoming midterms, coming to the opposite result from the Texas case. That is the principle at work here, and on a superficial level it makes sense.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But as Ginsburg — joined by Justices Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor — points out, the general reluctance to change election rules at the last minute is not absolute. In Wisconsin, using the new law would have created chaos. For example, absentee ballots would not have indicated that identification was necessary for a vote to count, so many Wisconsin voters would have unknowingly sent in illegal ballots.

In the Texas case, conversely, there is little reason to believe that restoring the rules that prevailed before the legislature's Senate Bill 14 would have been disruptive. "In all likelihood," the dissent observes, "Texas' poll workers are at least as familiar with Texas' pre-Senate Bill 14 procedures as they are with the new law's requirements."

And more importantly, some risk of disruption is a price worth paying to prevent an election from being conducted under unconstitutional rules. The Texas statute, which is extreme even by the standards of contemporary Republican vote-suppression efforts, is not remotely constitutional.

The Texas law has all the defects of every law that requires photo ID to vote. You don't have to take my word for it — you can read the recent tour de force opinion of the idiosyncratic, immensely influential Judge Richard Posner of the Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit in Chicago. Posner initially wrote an important opinion upholding an Indiana voter ID law, which was ultimately upheld by the Supreme Court. But last week, he concluded based on new evidence that the laws are "a mere fig leaf for efforts to disenfranchise voters likely to vote for the political party that does not control the state government."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The fundamental problem with the ID requirements is that they are a bad solution to a non-existent problem. Not only is voter impersonation exceedingly rare, even in theory it would be impossible to steal an election by having large numbers of people pretend they are other voters. Election thefts are accomplished by manipulating vote counts or manufacturing fake votes after the fact, not by having an army of impostors cast votes!

The costs in vote suppression, however, are real, and since voter ID laws don't accomplish anything, even miniscule costs cannot be worth it.

But the Texas law is much worse than typical voter ID laws. As the Ginsburg dissent explains, "[I]t was enacted with a racially discriminatory purpose and would yield a prohibited discriminatory result," and hence violates the Voting Rights Act (and, presumably, the Fourteenth Amendment). All voter ID laws are discriminatory in effect, but Texas public officials made little effort to hide the extent to which the laws were intended to suppress the minority vote to protect Republican incumbents from demographic change. Indeed, the only reason the law was able to go into effect in the first place was the Supreme Court's notoriously shoddy 2013 opinion gutting the Voting Rights Act.

In and of itself, this should be enough to prevent the law from going into effect. But the legal deficiencies of Texas' election law do not end there. None of the forms of ID required by the statute are available for free. As the dissenters note, the costs are not necessarily trivial: "A voter whose birth certificate lists her maiden name or misstates her date of birth," Ginsburg explains, "may be charged $37 for the amended certificate she needs to obtain a qualifying ID."

Texas is simply not constitutionally permitted to do this. The Twenty-Fourth Amendment forbids poll taxes, and the Supreme Court held in 1966 that "a State violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment whenever it makes the affluence of the voter or payment of any fee an electoral standard."

The fact that Texas' law is unconstitutional twice over — both by being racially discriminatory and imposing a direct cost on voting — is not a coincidence. Even after racial discrimination in voting was made illegal by the Fifteenth Amendment, for nearly a century states were able to use formally race-neutral measures like poll taxes and literacy tests to disenfranchise minority voters. The Texas law is very much part of this long and ignoble tradition.

Unfortunately, the Supreme Court's decisions in 2013 and 2014 allowing the Texas law to go into effect are part of another long and ignoble tradition: the Supreme Court collaborating with state governments to suppress the vote rather than protecting minorities against discrimination. As long as Republican nominees control the Supreme Court, this problem is likely to get worse before it gets better.

Scott Lemieux is a professor of political science at the College of Saint Rose in Albany, N.Y., with a focus on the Supreme Court and constitutional law. He is a frequent contributor to the American Prospect and blogs for Lawyers, Guns and Money.

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warming

Earth is rapidly approaching a ‘hothouse’ trajectory of warmingThe explainer It may become impossible to fix

-

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies end

Health insurance: Premiums soar as ACA subsidies endFeature 1.4 million people have dropped coverage

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred