The toxic cult of America's national interest

Only a misguided cult would exalt Henry Kissinger...

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In getting a handle on the basic foreign policy issues of our day — how to think about the NSA leaks, or what the hell to do about Syria — the basic intellectual divide isn't the one you'd immediately think of. It's not the split between Left and Right, or civil libertarians and security state hawks, or interventionists and non-interventionists.

It's between those who buy into the cult of America's national interest and those who don't.

The cult worships at the altar of American selfishness, the idea that the United States is justified in doing anything — including invading a "crappy little country" and ignoring the systematic slaughter of innocent foreigners — if it further America's "interests" in some vague fashion.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Of course, pure cultists are relatively rare, as are their opposites, cosmopolitans who believe American national interests should hold no special pride of place for American policymakers. But between the two extremes lies a diverse spectrum, and that spectrum holds the key to unlocking the real issues at stake in the American foreign policy debate.

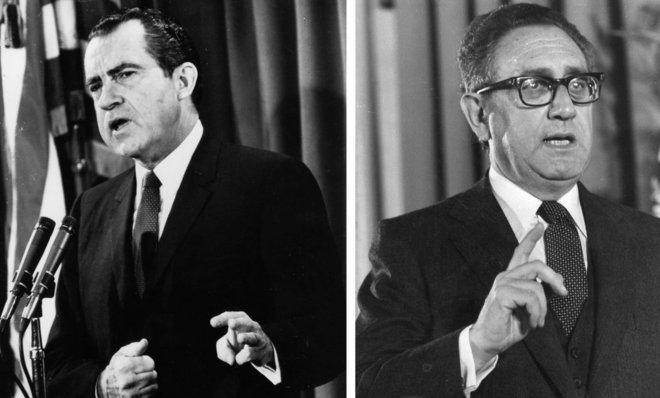

Perhaps the best way to understand the influence of the pole of the spectrum I've labeled "cultists" is to look at recent coverage of Henry Kissinger.

Nixon's national security adviser has been back in the news of late for doing what he does best: Aiding and abetting mass murder. Newly unearthed documents prove that, in 1976, Kissinger gave a clear green light to Argentina's dictator to launch a "counterterrorism" campaign in which thousands of Argentine civilians were killed or "disappeared."

The Argentine government was worried that what we now call the Dirty War would draw American human rights pressure. Kissinger was worried that a human rights law working through Congress would prevent Argentina from "finish[ing] its terrorist problem before year end."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The other spate of recent Kissinger coverage was prompted by a new book by Princeton professor Gary Bass, The Blood Telegram, marshaling damning evidence that Kissinger and Nixon were directly complicit in the systematic slaughter of Bangladeshi civilians. "Kissinger joked about the massacre of Bengali Hindus," Bass writes, "and, his voice dripping with contempt, sneered at Americans who 'bleed' for 'the dying Bengalis.'"

That quote isn't from Bass' book, but from a follow-up essay responding to one Robert Blackwill, the Henry A. Kissinger Senior Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations. Blackwill's defense of Kissinger's Bangladesh policy is, as Bass demonstrates, no more persuasive than a defense of Kissinger's illegal arm sales facilitating East Timorese genocide would be. Or his callous, unlawful bombing of civilian population centers in Laos and Cambodia. Or his material support for the coup against democratically elected Chilean President Salvador Allende.

While these new disclosures about Argentina and Bangladesh are making headlines today, much of the case against Henry Kissinger is widely known. Its most famous distillation is Christopher Hitchens' 2001 book, The Trial of Henry Kissinger. Yet, as Bass notes, official Washington treats Kissinger more like a celebrity than a war criminal. His 90th birthday party last year was a political who's who, and he spent August hamming it up with Stephen Colbert on national television.

Part of the reason for Kissinger's indefensibly exalted status is the insular chumminess of American elites. But another important explanation is that Kissinger's motivating principle — that the national interests of the United States axiomatically trump any moral considerations — holds real sway in the foreign policy establishment. Kissinger's crimes are forgiven, in other words, because he was acting in what he believed were America's best interests.

Kissinger's standing is not the only area where you can see this moral priority reflected; most notably there is the contrast between our paltry (by global standards) foreign aid spending and unjustifiably large defense budget. It's also reflected in political rhetoric; every political leader or foreign policy official justifies his or her preferred policies in terms of national interests. "It has become virtually a matter of faith among statesmen," writes the Navy War College's James Miskel, "that foreign policy is best made" by reference to particular national interests.

Not that America's foreign policy is exclusively selfish. Any serious account of U.S. history also finds real commitment to principles, like democracy, beyond what's narrowly good for America in power terms. That's obvious when you look at the global institutions the United States chose to build after World War II, binding the United States into a broadly liberal democratic global order. This is the familiar tension between American liberalism and realism one reads about in any international history book worth its salt.

But that familiar contrast, while useful in some general sense, fails to properly illuminate the moral divide that, below the surface, sets the terms of American foreign policy debate. That is, whether you believe the United States has moral obligations to foreigners, and at what point you believe those duties can trump America's obligations to its own citizens.

It's tempting to see this moral fissure as an extension of the Left/Right divide, with progressives broadly committed to treating all people around the world equally and conservatives valorizing nationalism as an institution worth preserving. That's certainly what Nixon was thinking when he complained to Kissinger about "crap from the liberals" over his support for the murderous Chilean coup.

That's too simple. Some liberals, like the brilliant philosopher John Rawls, believe governments ought not give foreigners the same kind of equal moral consideration they owe to all citizens. Neoconservatives believe America's moral duties to non-Americans require us to routinely intervene on their behalf; many paleoconservatives believe these duties obligate us to unconditionally respect the sovereignty of foreign governments. Attention to these moral divides is the only way to make sense of the web of the inter- and intra-ideological spats that demarcate the foreign policy battle lines.

Take the NSA surveillance debate, for instance. Snowden's muse, Glenn Greenwald, is an extreme left-wing cosmopolitan. He thinks there's no reason for the United States to value the lives of its citizens over those of foreigners. I find that one of his most appealing qualities, though he can take it pretty far overboard.

That position is Greenwald's defense of leaking documents that detail NSA spying abroad. Foreigners have privacy rights too, and our government must respect them. Some of his more nationalist liberal critics, by contrast, fret that the leaks are weakening the American state's position at home and abroad. The first part of that charge is pretty silly, but the second gets at a core issue Snowden raises: What are the limits of foreign privacy rights in the face of asserted American national interests?

These moral beliefs cross-breed with beliefs about the likely effects of policy, often producing strange-seeming results. For instance, quite a few cosmopolitan-minded liberals, of the sort generally sympathetic to backing humanitarian military intervention, opposed early plans to get involved in Syria because they would make the problem worse. I'm one of them.

But you've probably already guessed where I fall on the spectrum. The "cult" jab was a bit of a dead giveaway. Indeed, I do think that the national love affair with Henry Kissinger is incontrovertible evidence that the United States' moral compass is out of whack. While the spectrum of our moral thinking on foreign policy is clearly broad, it's equally clear that one band of it shines altogether too brightly.

Zack Beauchamp is a Reporter/Blogger for ThinkProgress. He previously contributed to Andrew Sullivan's The Dish at Newsweek/Daily Beast, and has also written for Foreign Policy and Tablet magazines. Zack holds B.A.s in Philosophy and Political Science from Brown University and an M.Sc in International Relations from the London School of Economics.

-

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far right

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far rightIN THE SPOTLIGHT Reactions to the violent killing of an ultra-conservative activist offer a glimpse at the culture wars roiling France ahead of next year’s elections.

-

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?the explainer They are distinguished by the level of risk and the inclusion of collateral

-

‘States that set ambitious climate targets are already feeling the tension’

‘States that set ambitious climate targets are already feeling the tension’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred