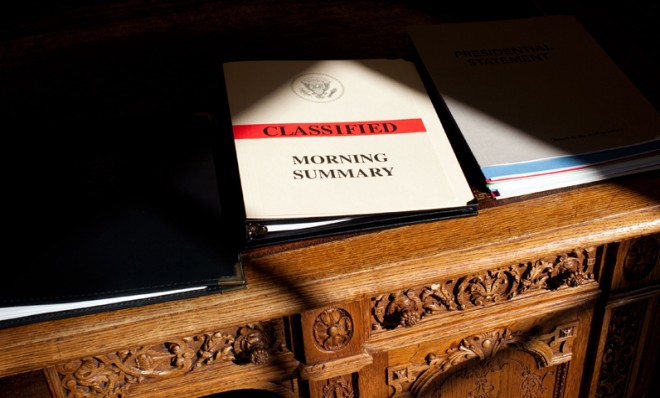

The government's ludicrous obsession with secrecy

There's little point in refusing to acknowledge the existence of drones, or "unpublishing" widely known information

Every one of the 300,000 diplomatic cables and military war logs released by WikiLeaks is available online, in a friendly, annotated, and searchable database. Anyone anywhere can shine a spotlight on that slice of U.S. activities abroad, and make assessments on the dispositions of various nations and the state of our relationships with them. But don't tell the American government. Officially, those cables are still classified and restricted. Government employees are not to access them. For all practical purposes, the documents don't exist.

The most obvious problem with such a policy is that our functionaries are put at a disadvantage when dealing with foreign counterparts. You can bet that anyone doing business with the United States has done his or her WikiLeaks homework.

But there is a less obvious and far more insidious problem. Government and military researchers are not allowed to "know" certain things. I recently spoke with a Defense Department employee who was working on a monograph on kinetic responses to a certain type of foreign threat. Valuable material gleaned from WikiLeaks was off-limits, and he was at a standstill until he could find some other source on the matter. This is obviously a huge inconvenience, but more importantly, the mindless insert-head-in-sand WikiLeaks policy of the U.S. government is setting back the kind of research that saves lives and wins wars.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

While researching our book, Marc Ambinder and I repeatedly encountered the CIA mantra, "Nothing is known until we confirm it." Under this rubric, a news story in the New York Times does not count as a source of fact — bona fide "facts" originate only from Langley, Virginia. This is absurd, of course. But even granting the notion that reality is conferred only by the state, a leaked diplomatic cable is not a sourced story. Rather, it is a primary source and an irrefutable fact. The cables should no more require official confirmation than does gravity or electromagnetism.

Meanwhile, it is a fact that until last month, the CIA operated an armed drone program. (Control of the program is reportedly being moved to the Department of Defense.) The whole world knows it. Such "partners" abroad like Pakistan have directly acknowledged it. The secretary of defense and the president have told jokes about it. Former U.S. officials have described it. Certainly the likely targets of the program were familiar with it. But the program is actually a highly compartmentalized secret. It might exist, and it might not — to even officially deny it is to recognize its existence as a possibility.

The weirdness of secrecy policy isn't limited to WikiLeaks cables and supposed wink-wink programs. The government has a penchant for classifying things that exist in the mass media. John Podesta, chief of staff for President Clinton and a force behind the modern Freedom of Information Act, described a battle he "won once out of every ten times." According to Podesta, "Sometimes, someone from the [National Security Council] would come into my office and hand me a newspaper article from overseas. It was marked 'C' for Confidential."

"I was quite an asshole about this, I admit," he said. "I would go to the NSC executive secretary down the hall and ask, 'Why is this classified at all? It's a newspaper article.' Then inevitably they would come back and say, 'It's classified because the president's interested in it and that is strategic information.' Okay. Yeah, right."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In 2010, Lt. Col. Anthony Shaffer, a former officer with the Defense Intelligence Agency, wrote a book recounting his time in Afghanistan. As is common for members of the intelligence community, his book had to be vetted by the government to make sure it revealed no classified material. The book, Operation Dark Heart, was approved by the Army and was published. Then the Department of Defense decided that the book contained sensitive material. Its solution? The government purchased the book's entire first run, and offered a redacted version for the second printing. As a consequence — in what is a perfect example of the insanity of government secrecy — interested citizens compared both versions of the book, and now we know precisely what the government wanted to keep secret.

This isn't the only example of the government attempting to "unpublish" something. In 1999, the intelligence community began reclassifying material that had previously been released into the public domain. By 2006, more than 55,000 open documents were re-stamped secret — never mind that researchers and historians already had copies of many of them. Among the retro-secrets crucial to the common defense? A 1948 plan to use balloons to drop propaganda leaflets behind the Iron Curtain, and a 1950 assessment that China would not intervene in the Korean War. (Two weeks after the CIA report was written, China sent 300,000 troops into Korea.)

In the case of the WikiLeaks cables, the American Civil Liberties Union in 2011 filed a Freedom of Information Act request for the (already publicly available) diplomatic cables related to such subjects as rendition and Guantanamo. True to form, the State Department cited secrecy, and refused to release some of the (already publicly available) documents. It released other cables with heavy redactions. Just as with Operation Dark Heart, these actions produced a perfect side-by-side comparison of documents, highlighting precisely the information that the government considers too secret for ordinary Americans. The ACLU sued, and the courts backed the State Department. An official document, the judge wrote, "is no substitute for an official acknowledgement."

Until secrecy policy in the United States is given sensible reform, this type of lunacy will prevail. The government will continue to classify material with wanton abandon; basic facts will simultaneously remain unofficially acknowledged and yet formally denied; and in a supreme act of stuffing genies into bottles, government agencies will continue trying to reclassify previously declassified material. The result will be the continued crumbling of the American deep state, and a well-deserved erosion of trust in the American government.

David W. Brown is coauthor of Deep State (John Wiley & Sons, 2013) and The Command (Wiley, 2012). He is a regular contributor to TheWeek.com, Vox, The Atlantic, and mental_floss. He can be found online here.

-

Political cartoons for December 15

Political cartoons for December 15Cartoons Monday’s political cartoons include Time's person of the year, naughty and nice list, and more

-

Who is fuelling the flames of antisemitism in Australia?

Who is fuelling the flames of antisemitism in Australia?Today’s Big Question Deadly Bondi Beach attack the result of ‘permissive environment’ where warning signs were ‘too often left unchecked’

-

Bulgaria is the latest government to fall amid mass protests

Bulgaria is the latest government to fall amid mass protestsThe Explainer The country’s prime minister resigned as part of the fallout

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration