How your local jail became hell: An investigation

Jail is the humble foundation upon which the incarceration nation rests. And it is has been totally corrupted.

When she was arrested on July 23, 2013, in Hawthorne, California, Sierra Zurn told the cops that she suffered from ulcerative colitis and had been prescribed Paxil for major depression. She says she brought up her medical conditions again when she was booked at the El Segundo police department. She mentioned it once more when she was transferred to the Century Regional Detention Facility. No fewer than eight different people, including a pharmacist, two nurses, and a nurse practitioner, were made aware of this fact, according to her medical records, which Zurn provided to The Week. "DEPRESSION" was stamped on her jail bracelet.

But the jail did not even give her any toilet paper, she told The Week, let alone her meds. In a grim irony, her very depression was cited as the reason she could not self-medicate.

Paxil, or paroxetine, is a powerful psychoactive drug with a short half-life in the body. Zurn had not had a dose since the day before her arrest. So when she got to the jail, she began experiencing serious withdrawal symptoms. Delirious, dizzy, paranoid, and sobbing uncontrollably, she says she was placed in solitary confinement, as is common for mentally ill people. Alone for 23 and a half hours a day, and still without toilet paper, Zurn refused to eat. After two days, she was released. It was her birthday. "It was the worst two days of my life," she told The Week.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

All this, and yet Zurn had not even been convicted of a crime. Zurn, you see, was in post-arrest detention, more commonly known as jail. She had been pulled over for a routine traffic stop, then arrested when the police found some marijuana in her car and accused her of transporting it to be sold.

"The modern American jail primarily houses the legally innocent."

When she was released, she thought that would be the end of it, since no charges had been filed and no judicial determination of probable cause had been presented. But a month later, she was officially charged with felony transportation of marijuana, which carries a potential sentence of four years in jail. Distraught at the prospect of more incarceration, Zurn attempted suicide.

After recovering, she went to court. The case had 16 continuances, two of which involved the arresting officer failing to obey a court order to appear, which dragged the process out for months. Finally, more than a year later, in October 2014, the case was dismissed "in furtherance of justice" after Zurn did some community service. In the meantime, she had filed an official complaint against the jail, but the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department responded that, after a "thorough inquiry," it had found no evidence to back her claims. She is now suing the department for abusive treatment. (The LASD did not respond to a request for comment; in response to a public records request, the department said there were no public records regarding Zurn's time in jail.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

With little recourse, Zurn turned to the one place that would hear out her complaint: She posted a review of her experience of the L.A. County jail system on Yelp. That's where I found her.

You might think that Zurn's story, while unfortunate, is relatively uncommon. You would be wrong. The modern American jail — which is distinct from prison, the place where those convicted of crimes go — primarily houses the legally innocent. There are 731,200 people inside American jails — substantially more than the population of Washington, D.C. — and three out of five of those inmates have not been convicted of anything at all.

The American jail is a support apparatus that serves the needs of the rest of the criminal justice system. That vast network of institutions — the police, the courts, state and federal prisons, parole boards, and so on — rests on this foundation. Before anyone goes to an arraignment, a trial, or state or federal prison, they go to jail.

Los Angeles County Sheriff's deputies inspect a cell block at the Men's Central Jail in downtown Los Angeles in 2012. | (AP Photo/Reed Saxon, File)

Jails are locally administered. They are usually fairly small. And there are a lot of them. There are over 3,200 jails in the U.S., a vast archipelago spread across the nation. All but the smallest counties have at least one, and many municipalities have them as well.

Technically, only dangerous criminals or flight risks are supposed to be detained before trial (which is an important service, to be sure). But the titanic machinery of the War on Crime, combined with sweeping cuts to public services, particularly in areas of mental health, have changed American jails into "massive warehouses primarily for those too poor to post even low bail or too sick for existing community resources to manage," according to a comprehensive new report from the Vera Institute of Justice.

Of course, not being convicted of a crime does little to change the character of time spent in jail. And because jails attract almost no media attention, because they are often run by corrupt or incompetent local officials, and because skinflint local governments often refuse to provide the money for decent conditions, in many cases jail time can be as unjust or brutal as that spent in state or federal prison — if not more so.

How jails abandoned "innocent until proven guilty"

The incarceration machine — or what scholars call the "carceral state" — started with Nixon's war on crime and drugs, which drastically increased the harshness of American sentencing practices, particularly for nonviolent offenses. Reagan got even tougher in 1984 with the Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984, which included the Sentencing Reform Act. The law created a commission to recommend uniform federal sentencing guidelines, ironically championed by Sen. Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts as a way to promote fairness and good government. But Reagan stacked the commission with hardliners, who drafted draconian rules strictly mandating harsh sentences with little room for nuance or mercy.

"The jail system had effectively criminalized poverty."

While those guidelines were softened by a Supreme Court decision in 2005 that made them largely advisory, for more than a generation district judges were straitjacketed into handing down extremely harsh sentences, regardless of mitigating factors.

As a result, the incarceration rate more than quadrupled from 166 per 100,000 Americans back in 1970 to 716 today, the highest in the world, save for tiny Seychelles. (Compare that to Great Britain's rate of 147, or Norway's 72.)

Jails were sharply affected by this development, according to Temple University's Melanie Newport, who studies the jail system. Jails were the first contact with a new flood of people being arrested, charged, and tried, and so were forced to increase capacity. "The number of jails doubled after World War II," she says. (It has technically been fairly stable since the 1970s, as smaller jails were consolidated into larger ones.)

State prisons form the biggest part of the American incarceration system, housing 1,362,000 inmates, according to a 2014 study by the Prison Policy Initiative. But jails are the second-biggest, with almost three-quarters of a million people incarcerated, more than triple the 209,000 convicts inside federal prisons.

The average jail term is quite short, which means that there is colossal churn in and out of the system — vastly increasing the number of people ground through the incarceration machine. There are 688,000 people released from all prisons annually, but nearly 12 million jail admissions each year.

Many of those people are mentally ill. The "deinstitutionalization" movement of the 1960s decimated state psychiatric hospitals by the mid-1980s. While this was a benefit to many people with minor mental problems or disabilities, very many of the seriously mentally ill were simply left without treatment.

A huge fraction of those people end up in jails or prisons. More than 40 percent of people with a serious mental illness have been arrested at some point. A 2006 study by the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that 64 percent of jail inmates have some kind of mental illness. Roughly 20 percent have a serious mental illness, like schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression. That makes almost 150,000 such people in jail, more than four times as many as in state hospitals.

Jails and prisons are now the major American institutions for handling the mentally ill — which often means locking people like Zurn in solitary confinement for being a nuisance.

All of this was exacerbated by the Bail Reform Act of 1984. A previous bail law mandated that only flight risks could be detained before trial, with the idea of minimizing pre-trial detention. But the law turned this idea on its head, making it much easier to detain people for fear of future crimes.

Conditions for bail grew only more stringent, as non-financial bail conditions were rolled back and bail amounts were jacked up over time. Per the Vera report, back in 1990, 60 percent of felony defendants were released before trial on non-financial conditions. By 2009, it was 38 percent. Between 1992 and 2009, average felony bail amounts increased from $38,800 to $55,400, adjusted for inflation.

Today, money is what matters most when it comes to who gets stuck in jail:

[Thirty-eight] percent of felony defendants will spend the entirety of their pretrial periods in jail. Yet, only one in ten of these defendants is detained because he or she is denied bail. The rest simply cannot afford the bail amount the judge sets. For example, in New York City in 2013, 54 percent of jail inmates held until their cases had been disposed remained in jail because they could not afford bail of $2,500 or less — with 31 percent of the non-felony defendants held on bond amounts of $500 or less. [Vera Institute of Justice]

The result of all these factors and historical trends is the mass incarceration of the legally innocent. Of jail inmates, fully 62 percent have not been convicted of a crime.

The jail system had effectively criminalized poverty. It was housing hundreds of thousands of mentally ill people. And it was plagued by chronic institutional incapacity, all with little to no oversight or media coverage. The stage was set for a systematic violation of constitutional rights.

The pervasive awfulness of jail

The brutality of the prison system is well known, and usually gets all the media and pop culture attention. But jails can be just as bad. Take the Los Angeles County jail system, where Zurn was locked up. It has been embroiled in scandal for the last several years. In 2011, an extensive ACLU report revealed a cabal of corrupt deputies who regularly and violently abused prisoners in their custody.

The resulting federal investigation was stoked by dozens of articles in The Los Angeles Times detailing hundreds of wrongful incarcerations, rampant violence, and other abuse. Seven deputies were eventually convicted for obstruction of justice.

"Send me to federal prison any day instead of county [jail]."

Similar stories abound. In 2011, the Department of Justice accused the Maricopa County jail system of inmate abuse and systematic racial profiling and illegal arrest of Latinos. The department filed a civil rights suit against the county that is still ongoing, and Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio (yes, that one) recently admitted to violating a court order to stop profiling Latinos. (The sheriff's office refused to comment for this article.)

Valencia County, New Mexico, was sued by a woman with bipolar disorder for keeping her in pretrial solitary confinement for two years. The county eventually settled for $1.6 million.

All horrifying stories. But at least someone noticed. Smaller jails rarely get the attention of local media, let alone the national media. A few years ago, for example, the Warren County Regional in Bowling Green, Kentucky, was sued for confiscating the cash and personal checks of arrestees admitted to the jail.

Kentucky law stipulates that convicts must help pay for the cost of their incarceration, as "required by the sentencing court." So the jail's officials "would stamp the back of the check with 'Warren County Jail, Inmate Account,' and take it to a local bank they have a relationship with," Kentucky attorney Greg Belzley told The Week. Add some stiff paperwork for clawing back one's property, and "they basically end up keeping the money." The system to request one's property back was so opaque that, to Bezley's knowledge, no one had ever even tried.

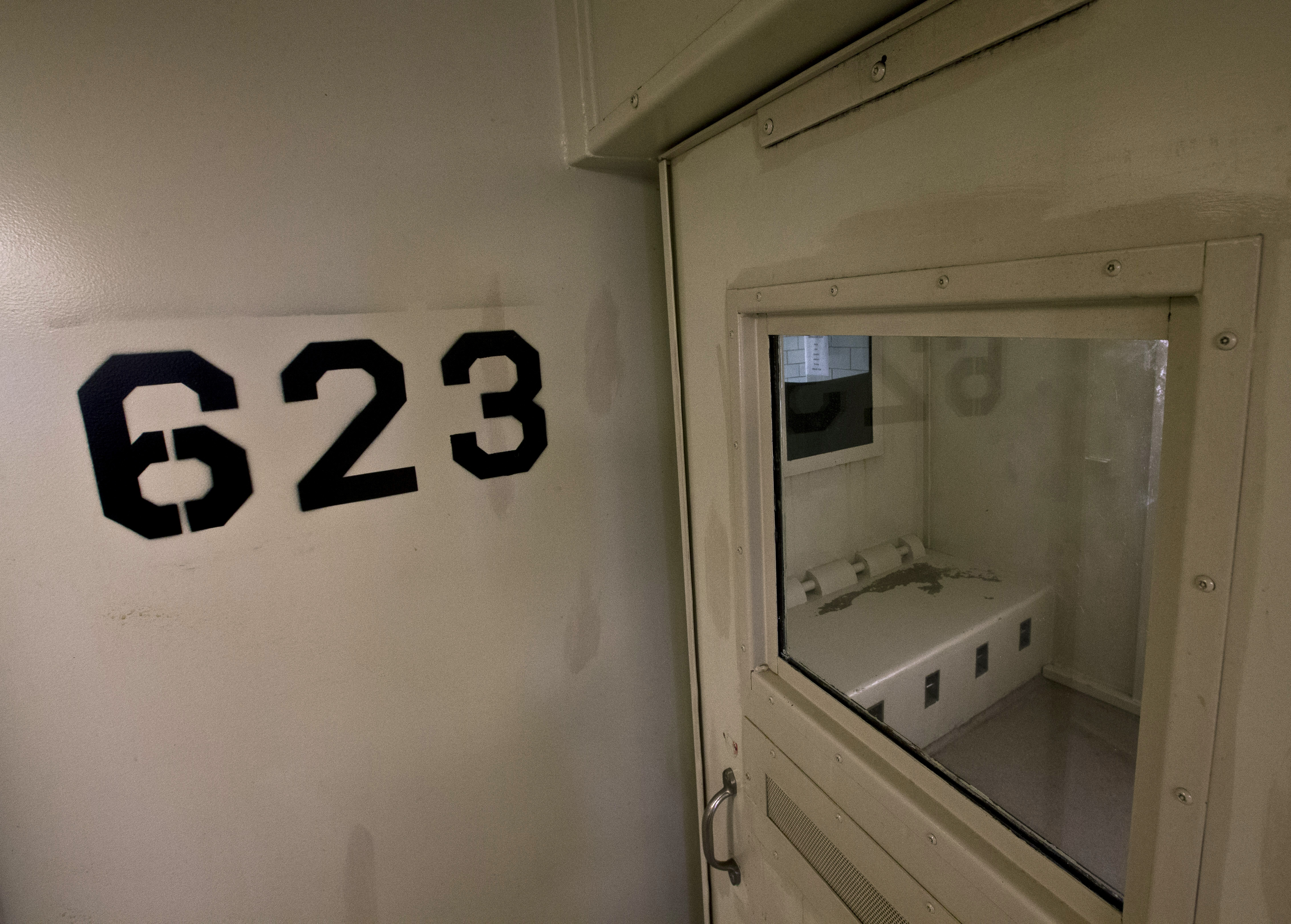

An isolation cell in the Dane County Jail in Madison, Wisconsin. | (AP Photo/Morry Gash)

Belzley represents former inmates who are suing the jail for violation of the inmates' constitutional rights. A circuit court judge ordered the jail to stop depositing arrestees' checks without approval, but agreed that the jail could confiscate cash to offset confinement costs. Belzley is appealing the decision. (In a written statement, a lawyer for the jail said the practice was legal, though it has been discontinued.)

This is actually one of Belzley's less awful cases. There are so few lawyers focused specifically on inmates' rights in Kentucky that he and his wife (they own a small firm together) typically "focus on wrongful death and serious injury" in jails and prisons.

David Fathi, director of the ACLU's National Prisons Project, says the rare cases that earn media or legal attention are just the tip of the iceberg. He says that any "place that houses politically powerless, unpopular people" with little to no oversight is going to have corruption and abuse.

Privatization makes everything worse

The incarceration machine has not escaped America's privatization mania. Indeed, jails and prisons are perhaps the worst targets for privatization, because the incentives are so perverse.

The very idea of a private prison service is at direct odds with the ostensible justifications for privatization, argues the ACLU's Fathi. A private prison offers none of the mechanisms by which free markets are supposed to work. Prisoners have no consumer choice. They have no political power. Their ability to take legal action is limited, and there is little oversight of the market in question.

Private probation companies — which run on the backs of probationers, what they call "offender-funded justice" — often serve to keep people in jail, not out of it. They profit from loading up probationers with fees, which can then be increased with penalties if they can't pay up, despite the fact that the Supreme Court ruled in 1983 that a probationer cannot be incarcerated for simply lacking the money to pay. That profit motive, combined with cash-strapped local governments relying on fees and fines to fill budget holes, has brought back the debtor's prisons of Dickensian infamy in many places — but this time as jails.

"People are dying, people are being ignored."

Meanwhile, private video-conferencing companies have been lobbying to shut down face-to-face visitation across the country in favor of webcam visits that would charge up to $1.50 per minute.

And while privatizing ancillary services like food or laundry might result in merely poor service, privatizing health care has been an utter disaster, because there is a structural incentive "to deny care to powerless people to increase profits," says Fathi.

Corizon Health, the biggest inmate health care contractor in the country, is responsible for 345,000 inmates in 27 states. The company recently settled the largest wrongful death case in California history for $8.3 million. In Arizona, a local media investigation alleged inadequate care by Corizon. In Alabama, where it has been sued by the Southern Poverty Law Center for inadequate medical care, a state auditor repeatedly gave the company failing marks. (Still, the company's contract was recently renewed.)

In New York City, a state watchdog cited Corizon, as well as local correctional and health agencies, for "gross incompetence" when a mentally ill inmate at Riker's Island was left alone for six days and died. In Florida, the company was fined $22,500 for contract violation in quality of care. The Allegheny County Controller in Pennsylvania recently released a blistering report on Corizon's management of the county jail there, accusing the company of multiple contract violations that endanger inmates and waste money.

(In a written statement, Corizon insisted that it provides the "best possible care to our patients," noting that of the hundreds of lawsuits filed against the company that have been closed, 87 percent were dismissed, administratively closed, or judged in Corizon's favor. About one-third of the lawsuits remain open.)

Belzley says the situation in Kentucky is little different. Health care contractors in the state, which include Corizon, have such a skewed nurse-to-doctor ratio that he has filed several wrongful death or serious injury lawsuits in which the supervising physician had never even met the alleged victim.

The only question is why people would be surprised jail contractors would do this. Why wouldn't they? It pays.

Why jail can be worse than prison

Many county jails, especially newer ones, are built like a single wing of a maximum-security prison. A full prison would have several "pods" arranged around a central yard, but small jails often are composed of a single pod. Inmates in such a place often have no access whatsoever to outside air, and no windows of any kind. They are often not even allowed to meet face-to-face with visitors, with whom they have to interact via an expensive webcam.

A Ward County sheriff's deputy monitors jail cells via surveillance cameras in Minot, North Dakota. | (AP Photo/Eric Gay)

Such a facility is very expensive to build, of course. There is always money for bigger and stronger cages. But money for treatment or rehabilitation programs is practically nonexistent. Often, jails are virtually devoid of diversions at all, save for a television and a tiny "library" of a few dozen books.

Even in places with some diversions, they are often reserved for longer-term inmates. The Breckinridge County jail in Kentucky, for example, has both county and state inmates. According to Christopher Travis, who spent 45 days there for violating a domestic violence order, the "ones that were sentenced to five years plus...get all the activities." County-side inmates, while they do get a small church and recreational time, are "locked down 23 hours per day." Even the Alcoholics Anonymous chapter is closed to county inmates, he says. (In an emailed statement, the Breckinridge County jailer disputed this story, saying that, generally speaking, "all inmates [in] both state and county are afforded the same opportunities.")

"Send me to federal prison any day instead of county [jail]," says another former inmate who spent time in both places for robbing a gun store. He asked not to be identified. "The food is better in prison, company is better, and there are less fights."

In jail, there is "much less programming or constructive activities," the former inmate says. It is "a much more volatile place," adds the ACLU's Fathi. People in prison have had time to adjust, and they know what's coming. Prison officials at least know something about the people they're overseeing. But people in jail have typically just been arrested. They're often traumatized by recent violence, detoxing from some substance or the other, or, like Sierra Zurn, simply denied the meds they need.

Even when jails do have protective measures, it doesn't guarantee their use, according to David Collingsworth, who by his own account has been "in and out of jail for 30 years." (He's now a producer for the Prison Show, a radio program about inmate issues.) Decades ago, "there was no such thing as a safe jail," but now there are all manner of monitoring and surveillance techniques that ought to make running a safe jail easily possible. But in the Harris County jail, the largest in Texas, "people are dying, people are being ignored...there's no reason for it," he told The Week.

"The first principle of jail reform is keeping people out of jail."

The Department of Justice is investigating the Harris County jail for the second time in six months over an inmate's death. From 2001 to 2006, there were 101 inmate deaths there, at least 72 of whom had not been convicted of a crime. From 2007 to today, there have been an additional 106 deaths. (In a statement, a Harris County Sheriff's Office representative pointed out that average deaths per year have fallen from over 16 to 11 since the new sheriff took office, and that the jail's suicide rate is below average for a jail of its size.)

Perhaps not surprisingly, suicide rates are extremely high in jail. Even a short time in jail can be highly dangerous. "The highest-risk time [for suicide] is the first 24 to 48 hours after a person is arrested," says Fathi.

As of 2012, the rate of suicide among the general population was 12.6 per 100,000 people. According to a Bureau of Justice Statistics report, the suicide rate among state and federal prisoners is somewhat higher, at 16. But in American jails in 2012, the rate was 40.

What is to be done?

The local nature of the American jail is at the heart of why the system is such a disaster. "This is a federalism problem," says Newport of Temple University.

At every level, local control exacerbates the hell of jail. Local sheriffs often have little to no experience in jail management, let alone mental health or rehabilitation. Local media systematically ignore jails, and local polities are less likely to pony up the cash to provide reasonable conditions.

There is a silver lining here. The overall size of the jail system, like that of the whole incarceration machine, may have already peaked. While a suicide rate of 40 is still far too high, it has fallen from 129 in the early 1980s. Crime has also plummeted since the peak of the great 20th century crime wave more than two decades ago: The property crime rate is down 41 percent, the violent crime rate down 49 percent, and the murder rate down 49 percent. This both eases the political pressure to crack down on crime and makes the staggering expense of jails less easy to justify. Of the $60 billion spent annually on the whole incarceration system, a third is spent on the local level — an increase of 235 percent from 1982 to 2011, according to the Vera report.

That has inspired some initial steps towards reform, especially in the larger jurisdictions. New Orleans has experimented with issuing summons instead of arrests for minor offenses, sharply reducing jail intake. Several communities have tried diverting minor offenders away from the criminal justice system and into community services. One New York district attorney last year simply stopped prosecuting all minor marijuana cases.

Other state-level laws allowing for compulsory psychiatric treatment in some circumstances, like Kendra's Law in New York and Laura's Law in California, also provide a framework to keep the severely mentally ill out of jail. Initial steps in this direction are ongoing.

There is also at least one change that can be made at the federal level. The 1984 Bail Reform Act made it far too easy to detain people before trial. Detaining those who are a flight risk or likely to commit more crimes is one thing, but it is absolutely indefensible for any person to be incarcerated because of an inability to pay. Poverty is not a crime. And as previous research from Vera demonstrates, the size of bail has little impact on preventing flight or new offenses. Ironically, relying on increased bail sometimes backfires, since it can free high-risk people who have the means to pay.

There is something of a bipartisan coalition building to reform the criminal justice system — a project that is still in its infancy, and mainly focused on state and federal prisons so far. But the main area of agreement between left and right — that the incarceration machine is way too expensive — raises the hackles of jail experts. The money question is "the most terrifying reform conversation," says Newport, because plain old stinginess is a big part of the problem in the first place. She argues that it is and should be "expensive to provide constitutional detention."

However, this monetary framework does have its benefits. Every expert I interviewed agreed that the first principle of jail reform — and of saving money on incarceration — is keeping people out of jails. Even progressive measures that cost money upfront can save money in the end. For example, the police in Portland, Oregon, have partnered with local mental health professionals to give appropriate care to addicted, intoxicated, or mentally ill people who end up in jail. It saved the city $16 million from 2008 to 2010 alone, per the Vera report.

But if those benefits are to be realized, the rights of the incarcerated must be at the top of the list of priorities. We won't get people out of jail "if human dignity isn't first and foremost," says Newport.

Media has a part to play as well, by bringing public attention to abuses. It's often only after scandals become public that reforms are made. In Los Angeles County, where Sierra Zurn was incarcerated, scathing media reports and the federal investigation led to a number of reforms in the jailing system. Last year, the suicide rate dropped by half.

But media alone does not have nearly enough power or reach to closely monitor thousands of jails. The above reforms all depend on the whims of local jurisdictions, the vast majority of which simply don't pay attention to their jails. Indeed, whether jails should remain in local hands "ought to be part of the policy conversation," says Newport. For reform to happen, "there has to be political pressure, because jails are a political institution."

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

US citizens are carrying passports amid ICE fears

US citizens are carrying passports amid ICE fearsThe Explainer ‘You do what you have to do to avoid problems,’ one person told The Guardian

-

All roads to Ukraine-Russia peace run through Donetsk

All roads to Ukraine-Russia peace run through DonetskIN THE SPOTLIGHT Volodymyr Zelenskyy is floating a major concession on one of the thorniest issues in the complex negotiations between Ukraine and Russia

-

Why is Trump killing off clean energy?

Why is Trump killing off clean energy?Today's Big Question The president halts offshore wind farm construction

-

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdown

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdownSpeed Read

-

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figures

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figuresSpeed Read

-

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancing

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancingSpeed Read

-

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens dead

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens deadSpeed Read

-

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictions

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictionsSpeed Read

-

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 dead

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 deadSpeed Read

-

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trial

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trialSpeed Read

-

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapse

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapseSpeed Read