The surprising economics of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch

A new study shows that it's not about how much waste you produce, but how you process it

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

If you haven't already, meet the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a collection of oceanic junk that has ballooned over the last four decades.

No one is sure how big it is, but it's probably enormous. A new study in Science Magazine tried to pin down some firm numbers by digging into various data: waste generation per person, the portion of that waste that's plastics, the size of populations near the coast, and the quality of countries' waste management systems. The researchers surveyed 192 countries, and found that, between them, humanity dumped 10.5 billion to 28 billion pounds of plastic waste into the oceans in 2010 alone — about 1.3 times the weight of Egypt's Great Pyramid at Giza.

The study also contains some valuable lessons about the nature of economic development, and how wealth creation can paradoxically be both friend and foe of the environment.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Now, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch isn't actually a "patch." It's more like a vortex that circulates along the natural currents of the Pacific Ocean: millions of small, often microscopic bits of plastic junk in the water column, stretched over about 5,000 square kilometers. And there's at least two, a western and an eastern patch.

There's circumstantial evidence that it's killing filter-feeding animals and birds — especially albatrosses that mistake the plastic for food — and it's definitely allowing certain invasive species to thrive and spread, throwing whole marine ecosystems out of whack.

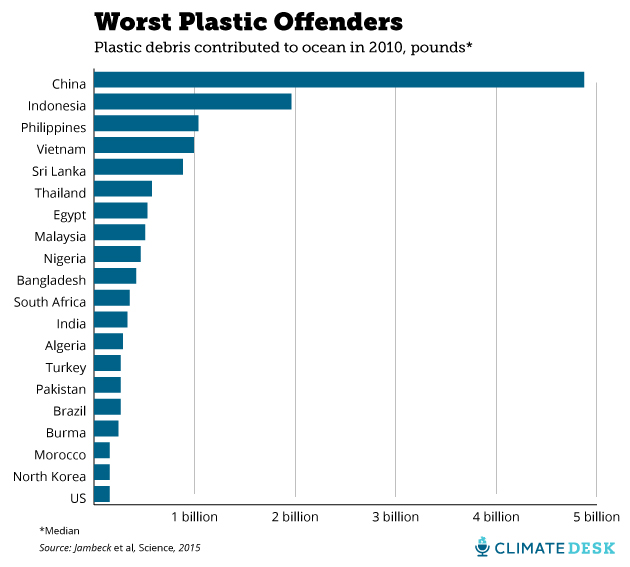

The sizable majority of the trash originates on land instead of coming from ships or boats. But what the study found that's really interesting is who's contributing:

The United States isn't exactly doing great here. It's in the top 20 offenders out of 192 countries. (And if you treated Europe as one entity, it would be in the top 20, too.) But as you can see from the chart, America is a minor contributor compared to poor and developing countries, especially Indonesia and China.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Environmentalists sometimes freak out over population growth, but that's not the driver here. China has four times as many people as the United States, but 25 times the waste output. The Chinese are just dumping way more garbage into the ocean per person. The portion of the population that's coastal plays a big role, but both the U.S. and China boast big shares of their populations living near the ocean.

As Jenna Jambeck — an environmental engineer at the University of Georgia, and the study's lead author — explained to Science, the maturity of each country's waste management system seems to be the big factor:

What we're finding is that, in countries that are in rapid economic development, waste management infrastructure is sometimes one of the last items to be addressed in development. Often times, as engineers and as societies, we will address acute matters like clean drinking water [first]. And so sometimes waste can sort of get pushed to the side until later. And we're seeing a lot of middle income countries that are developing that just haven't been able to address the waste management infrastructure problem yet. [Science Magazine]

It's hard to overstate the sheer scale and pace of the economic change that's going on in the developing world right now, particularly in China and India. They're playing catch up, adopting economic methods already pioneered by the developed world. And they're doing it an astonishing rate that's putting enormous pressure on the global ecosystem.

You can see that in the study's projections. China's waste output into the ocean is expected to double between 2010 and 2025, and India will far more than double. The United States will increase as well, but at a much smaller rate and from a much lower baseline.

This dynamic is actually common. The economics of ecosystem use is still pretty young, but what you generally find is that poor and up-and-coming countries — in South America, Africa, and Asia — do the most damage in areas like land use, ranching, farming, water consumption, etc. If you break down the data from the Global Footprint Network, China exerts far more pressure on its ecosystems per capita than America in terms of crops, grazing, foresting, and fishing.

But where America blows everybody out of the water is carbon emissions per capita. That's what gives you those numbers about how we'd need four or five planets for everyone to live like Americans do.

The critical thing to realize is that China and other similar countries largely have to be in this position. They're trying to lift the living standards of hundreds of millions of people, and the decrease in extreme poverty over the last three decades is one of the great global humanitarian achievements. As Jambeck says, economic development is both the cause and the solution: as China and others pass through to the other side of the process, their waste management infrastructure will catch up, bringing their per capita waste creation more in line with America's. It should play out the same way in areas like cropland use, forestry, etc.

But America has little excuse. Its carbon footprint is three times that of France or Switzerland. The problem is systemic: our energy infrastructure is horribly inefficient, and our fuel mix is terrible. Even a homeless person here has a bigger carbon footprint than people in the rest of the world.

We could turn our economy into a gigantic national laboratory for green energy and infrastructure by putting a price on carbon emissions, either through a cap-and-trade system or a carbon tax, and by offering government prizes for research breakthroughs. We could then export that technology, helping China and the developing world achieve better standards of living by a more environmentally-friendly path. And we've got more than enough wealth per person to help out poor Americans, should these policies increase energy costs.

But we haven't done any of this. Not because of economic reasons, but because we just can't be bothered.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy