The quest for the perfect diet

A spate of recent studies has upended decades of established dietary advice about eating fat. Is fat now good?

What should we eat?

Mostly vegetables. Veggies of all kinds and colors, including salads and other leafy greens, are loaded with various types of phytonutrients and antioxidants that are essential to healthy living. Many recent studies have shown that people who eat more vegetables and other plant-based foods — such as beans, whole grains, fruits, and nuts — tend to have lower rates of heart disease and other chronic health issues than those who mainly consume animal-based products like meat and cheese. But researchers have also recently discovered that fat, maligned for more than 40 years as the leading cause of weight gain and high cholesterol, can also be part of a healthy diet. "Americans were told to cut back on fat to lose weight and prevent heart disease," says Dr. David Ludwig, an obesity specialist at Boston Children's Hospital. Today, "there's an overwhelmingly strong case to be made for the opposite."

Can fat really be good for us?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Yes, but not all fats are created equal. Foods like beans, nuts, and fish, which are rich in monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, are strongly linked to good cardiovascular health. But several recent studies found that even the saturated fats in red meat, butter, and cheese can be consumed in moderation, and that foods high in cholesterol do not raise cholesterol levels in most people. Those findings run counter to decades-old dietary guidelines from the American Heart Association and the U.S. government, which stated that people should avoid saturated fats because they clog our arteries, causing heart attacks and strokes.

How did we get it so wrong?

Blame bad science. In 1970, a University of Minnesota physiologist named Ancel Keys published his landmark Seven Countries Study, which examined diets across Europe, the U.S., and Asia. He concluded that people who ate a lot of meat and dairy, like Finnish lumberjacks, died from heart attacks at far higher rates than farmers in Crete, whose fish-, fruit- and grain-heavy diet was lower in saturated fats. Critics noted many mistakes in Keys' study — he looked at the Cretan diet during Lent, when the islanders had given up meat and cheese — but his conclusions were widely accepted because they seemed to make sense. After all, saturated fats are known to raise LDL, or "bad" cholesterol, and higher levels of LDL are a leading indicator of heart disease. But now there is increasing evidence that the type of LDL particles associated with saturated fats, known as pattern-A, are not harmful. "The argument against fat was totally and completely flawed," says Dr. Robert Lustig, president of the San Francisco–based Institute for Responsible Nutrition.

What effect did Keys' study have?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In 1980, the federal government issued its first set of dietary guidelines, telling everyone over age 2 to avoid fat. America didn't get any healthier. Adult obesity rates nearly tripled over the next three decades to 35 percent, while adolescent obesity rates quadrupled. The U.S. now spends $190 billion a year treating obesity-related conditions. The government-backed campaign against fat backfired in part because Americans replaced the calories they got from milk and cheese with calories from refined carbohydrates like white bread and pasta. Carbs turn into sugar in the bloodstream, which increases insulin production and encourages cells to store fat instead of burning it. With less energy available to fuel the body, the metabolism slows down, hunger sets in, and the process repeats itself.

Does that mean carbs are the real problem?

The case against them is strong. But if the low-fat era has proved anything, it's that focusing on just one aspect of a person's diet can have unintended consequences. Human physiology is simply too complex for the effects of an individual foodstuff or nutrient to be isolated and properly understood. "We should not be singling out particular components in food and vilifying them," says Catherine Collins, head dietitian at St. George's Hospital in London. "We should be promoting a balanced diet with a lot of variety, including some lean meat, fish, whole-grain cereals, fruit and vegetables, even a little wine if you like. Essentially, it's the Mediterranean diet."

Is that the ideal diet?

Possibly, but we can't be 100 percent sure because almost all dietary studies are observational and so have a fundamental limitation. Scientists will monitor the eating habits of test groups for years or even decades, and then draw associations between the subjects' diet and the diseases they suffer. Such an observational study might show that individuals who eat more vegetables tend to live longer, but it can't prove causation — that eating more veggies is the reason for that longer life span. Many nutritionists say their best advice is for people to stop obsessing over individual aspects of a particular diet and focus instead on choosing naturally produced foods and avoiding processed foods that are loaded with additives and excess sugar. "If you eat direct from nature, nutrients tend to take care of themselves," says Dr. David Katz, director of Yale University's Prevention Research Center. "The cold, hard truth is, the only way to eat well is to eat well."

If fat's OK, what about cholesterol?

For decades, health officials have warned Americans about the dangers of eating foods high in cholesterol, like eggs, shrimp, and lobster. But in a stunning reversal, the U.S. Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee recently recommended no longer listing cholesterol as a "nutrient of concern." That turnaround is in keeping with mounting evidence that for most healthy adults, eating foods high in cholesterol does not significantly contribute to the amount of cholesterol found in the blood — most of which is produced naturally by the body. Doctors warn that individuals with health problems such as diabetes or heart disease should continue to avoid high-cholesterol foods, but such foods' overall impact on good health may be less significant than was previously thought. "It's turned out to be more complicated than anyone could have known," says Wake Forest University biochemist Lawrence Rudel. "Eating too much a day won't harm everyone, but it will harm some people."

-

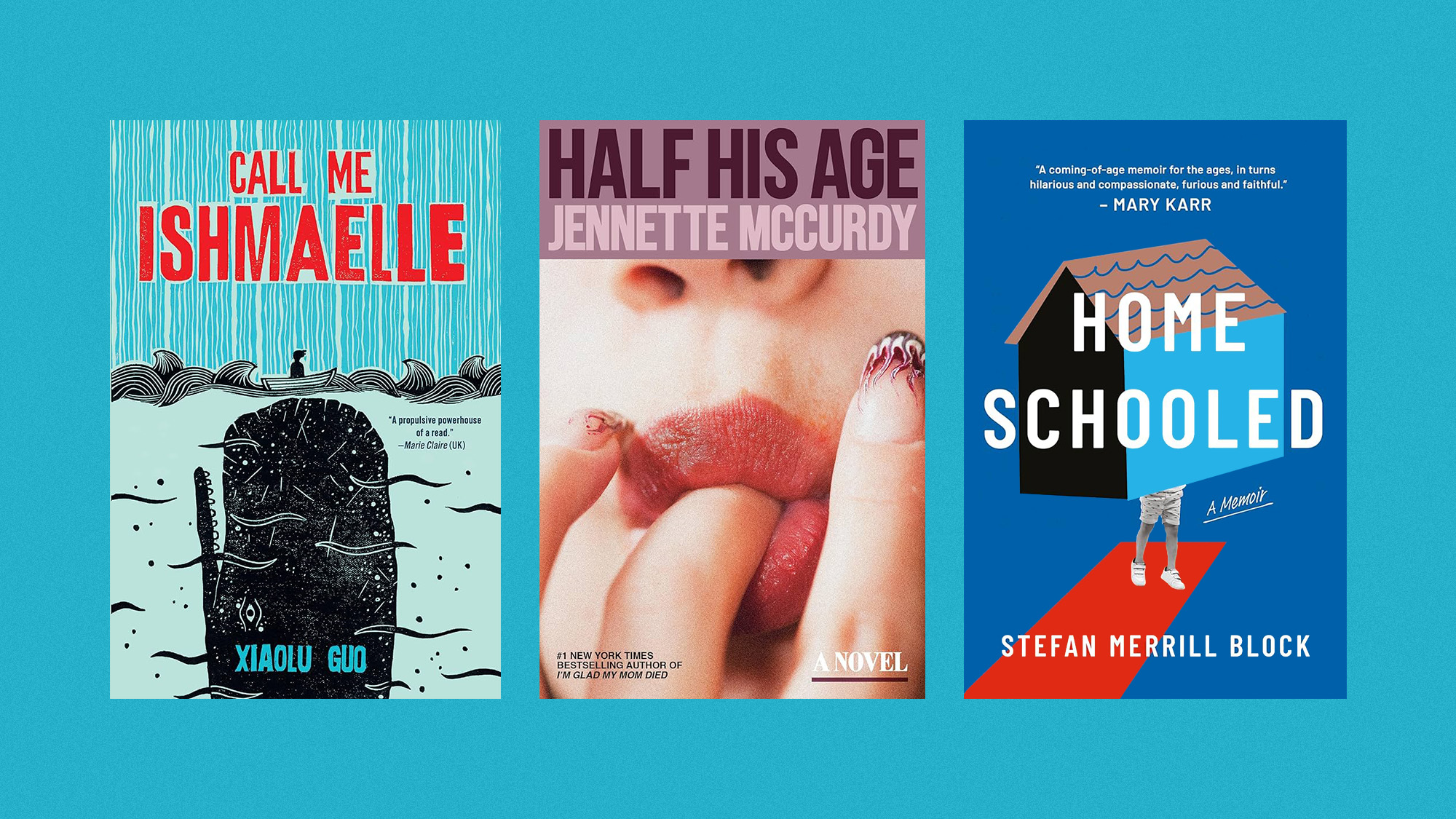

January’s books feature a revisioned classic, a homeschooler's memoir and a provocative thriller dramedy

January’s books feature a revisioned classic, a homeschooler's memoir and a provocative thriller dramedyThe Week Recommends This month’s new releases include ‘Call Me Ishmaelle’ by Xiaolu Guo, ‘Homeschooled: A Memoir’ by Stefan Merrill Block, ‘Anatomy of an Alibi’ by Ashley Elston and ‘Half His Age’ by Jennette McCurdy

-

‘Jumping genes': How polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming Arctic

‘Jumping genes': How polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming ArcticUnder the radar The species is adapting to warmer temperatures

-

Venezuela’s Trump-shaped power vacuum

Venezuela’s Trump-shaped power vacuumIN THE SPOTLIGHT The American abduction of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro has thrust South America’s biggest oil-producing state into uncharted geopolitical waters

-

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'The latest biography on the elusive tech mogul is causing a stir among critics

-

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!The Explainer Please allow us to reintroduce ourselves

-

The Oscars finale was a heartless disaster

The Oscars finale was a heartless disasterThe Explainer A calculated attempt at emotional manipulation goes very wrong

-

Most awkward awards show ever?

Most awkward awards show ever?The Explainer The best, worst, and most shocking moments from a chaotic Golden Globes

-

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. deal

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. dealThe Explainer Could what's terrible for theaters be good for creators?

-

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'The Explainer Move over, Sam Elliott and Morgan Freeman

-

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020feature So long, Oscar. Hello, Booker.

-

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortality

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortalityThe Explainer This film isn't about the pandemic. But it can help viewers confront their fears about death.