Is the U.S. economy immoral?

The answer to that question is neither as simple nor as clear-cut as Bernie Sanders suggests

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When Democrat Jerry Brown ran a longshot presidential campaign back in 1992, he snarkily referred to Bill and Hillary Clinton as "Bonnie and Clyde," the Depression-era bank robbers. Brown, now the governor of California, thought he had a legitimate chance to win the nomination. He wasn't going to let some delicate notion of political etiquette stand in his way.

Don't expect that kind of tough talk from Bernie Sanders, another longshot Democratic presidential candidate challenging a Clinton. During his announcement Tuesday, all the socialist Vermont senator had to say about Hillary Clinton was that his campaign "is not about Hillary Clinton."

That's not exactly surprising. The socialist Sanders almost certainly doesn't believe he will defeat the Clinton machine and be the Democratic Party's next presidential nominee — much less America's next president. So there's no reason to play attack dog. More likely what Sanders really wants is a big stage to highlight what he sees as the terrible unfairness and inequality of the modern U.S. economy, one where Americans have "a choice of 23 underarm spray deodorants or of 18 different pairs of sneakers when children are hungry in this country." In other words, the economy is just dandy at generating wealth, but that prosperity only benefits a few.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This is hardly a novel observation on the left. Clinton will likely campaign on a similar theme, though probably stated less provocatively. The New York Times reported that at a meeting with economists earlier this year, she said we needed a "toppling" of the wealthiest 1 percent. And recently, the Center for American Progress, a think tank with deep ties to Clinton, sponsored a lengthy report decrying income inequality and calling for "inclusive prosperity."

But Sanders goes much farther, and makes a deeper point when he talks about what's driving inequality:

The issue of wealth and income inequality is the great moral issue of our time, it is the great economic issue of our time, and it is the great political issue of our time… This grotesque level of inequality is immoral. It is bad economics. It is unsustainable. This type of rigged economy is not what America is supposed to be about. This has got to change and, as your president, together we will change it. [Bernie Sanders]

This sort of sweeping rhetoric connects with progressives at an almost visceral level. After listening to Sanders, many liberals are probably ready to grab the pitchforks and head to the nearest mansion or mega-bank to demand their fair share.

But here's the thing: Effective solutions require an accurate diagnosis of the underlying problem. For example: It matters whether a bridge collapsed because a recent earthquake was too strong or because bridge inspectors were bribed to approve shoddy construction. Similarly, it matters whether higher inequality is mostly the result of powerful interests immorally rigging the game or of impersonal macroeconomic factors, specifically technology and globalization.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Let's consider just one small slice of the economy, and one that is often decried by liberals as being highly immoral and unfair: executive compensation. Why have CEO pay packages, by some measures, greatly outpaced worker wages in recent decades? Sanders would point the finger at CEOs manipulating pliant corporate boards. The 0.1 percent and 0.01 percent all taking care of each other, at the expense of the rest of us. But a new study suggests the story isn't so simple. The National Bureau of Economic Research working paper "Firming Up Inequality" finds that earnings inequality hasn't risen because the best paid workers at companies now make a lot more than they used to compared to everyone else at their respective firms. Instead, the authors find "strong evidence that within-firm pay inequality has remained mostly flat over the past three decades." What has changed is the pay gap between firms. Workers at the higher-paying firms now make a whole lot more than they used to versus those at lower-paying firms. Why would this be? Maybe some companies are paying a premium for highly specialized, highly educated employees in response to a more globalized, technology-centric economy. It might not just be because powerful players are rigging the game!

Likewise, economists Steven Kaplan and Joshua Rauh find in their 2013 paper "It's the Market: The Broad-Based Rise in the Return to Top Talent" that technology has enabled highly talented and educated individuals — including private and public CEOs and hedge fund managers — to perform on a larger scale, "applying their talent to greater pools of resources and reaching larger numbers of people, thus becoming more productive and higher paid.”

Now, this isn't to say every CEO deserves what he or she makes. Nor does it mean we should just passively accept market outcomes. But it does mean that endemic unfairness in the U.S. economy is more complicated than some progressive nightmare of a bunch of Scrooge McDucks rigging the world's largest economy so they can add more gold to their personal money bins.

As I noted in another column here at The Week, when inequality researcher and best-selling author Thomas Piketty was asked what do about inequality, he conceded that "the main policy to reduce inequality is not progressive taxation, is not the minimum wage. It's really education."

If Bernie Sanders is looking for immorality in America, he can start with our underperforming schools.

James Pethokoukis is the DeWitt Wallace Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute where he runs the AEIdeas blog. He has also written for The New York Times, National Review, Commentary, The Weekly Standard, and other places.

-

Judge blocks Hegseth from punishing Kelly over video

Judge blocks Hegseth from punishing Kelly over videoSpeed Read Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth pushed for the senator to be demoted over a video in which he reminds military officials they should refuse illegal orders

-

Trump’s EPA kills legal basis for federal climate policy

Trump’s EPA kills legal basis for federal climate policySpeed Read The government’s authority to regulate several planet-warming pollutants has been repealed

-

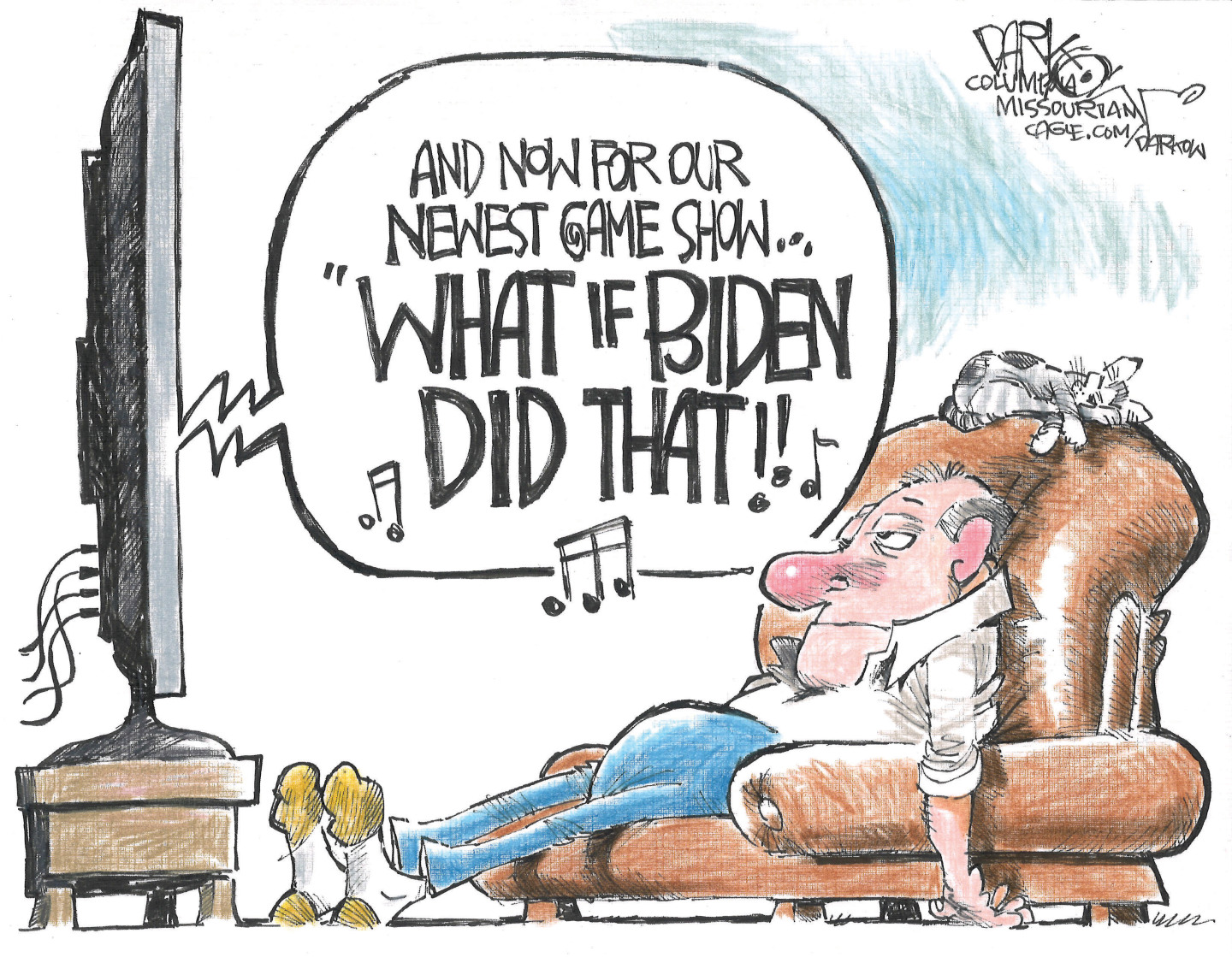

Political cartoons for February 13

Political cartoons for February 13Cartoons Friday's political cartoons include rank hypocrisy, name-dropping Trump, and EPA repeals

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred