The racial disparity at the doctor's office isn't getting better. It might actually be getting worse.

To the patients of the future, doctors are increasingly going to look like a blast from the past

For 30 years, Dr. Lawrence Sanders has been hearing that doctors need to look more like America. Needless to say, progress has been slow.

In 2014, only 5.5 percent of physicians and surgeons identified as African-American, according to a Bureau of Labor Statistics annual report, and only 6.3 percent as Hispanic. Sadly, that probably won't change in a meaningful way anytime soon.

Out of over 85,000 students in medical schools last year, only 5,000 identified as black and only 3,000 as Hispanic. And only 12 percent of current medical school graduates are black, Native American, or Hispanic, according to data from the Association of American Medical Colleges, or AAMC.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Advocates say that lack of diversity doesn't bode well for a country that is increasingly heading in the other direction, becoming more diverse as demographics shift.

By 2050, the populations that the U.S. government labels minority today — including African-Americans, Hispanics, Native Americans, and Asians — will comprise more than 50 percent of the population, making the U.S. a "majority-minority" nation for the first time, according to census estimates. One in every three Americans is expected to be Hispanic.

At the same time, Americans are growing older, fast. Demographers expect 2056 will mark the first time that the number of Americans 65 and older will exceed the number of Americans under 18.

That has implications for health care, with a "physician shortage" expected by 2025. With demand rising from increasing numbers of older adults, the country will be short an estimated 12,000 primary care doctors and 27,000 specialists — and that number could easily rise, according to AAMC research.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

All this combines to make the need for a robust and diverse health-care workforce hard to ignore. As the nation grows simultaneously older and less white, patients will increasingly find that medical professionals don't look like them, reflect their experiences, or understand their choices, researchers say. This has real implications for the nation's health.

Despite decades of medical advancement and improvements in hospitals, non-white Americans still suffer disproportionately from higher rates of diseases like diabetes and routinely get lower quality health care than their white compatriots.

The contrasts are sharp: Black patients wait on average twice as long as white ones for kidney transplants; black women suffering from breast cancer have a 67 percent higher likelihood of dying from the disease than white women; and Hispanic and African-American populations have higher incidences of adult diabetes than whites, according to 2012 findings from the Health Professionals for Diversity Coalition.

Some of this burden can be chalked up to poverty — the CDC found in 2013 that adults who did not graduate from college or who had lower household incomes suffered from diabetes at a higher rate, regardless of race — but not all of it can.

African-Americans and Hispanics had less access to overall healthcare than whites, according to a 2010 study from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. That study found that African-Americans were more likely than whites to leave a hospital emergency room without ever having received treatment, Asian patients were more likely to miss necessary vaccines, and Hispanics were more likely to lack a regular doctor.

"In many underserved neighborhoods and communities, access to health care becomes a challenge," Sanders, who teaches at the historically African-American Morehouse School of Medicine, said. "More often than not, African-American and other minority physicians are more likely to relocate to those areas."

At Morehouse, the need in underserved communities is emphasized, Sanders said, and many students choose to work as primary care doctors.

The issue of health care equality also hasn't gone unnoticed by lawmakers. In 2011, the federal government produced a multi-year strategy to reduce the gaps. The Department of Health and Human Services, which manages the program, announced it will work primarily through the auspices of the Affordable Care Act to get more people primary care providers, health insurance, and foreign language translators.

Many states also have some form of legislation on their books that promotes diversity in health care, either by recruiting diverse students for medical schools, collecting specific data on outcomes, or creating commissions to study the issue. Lawmakers in states like California, which may see a population boom in coming decades, have proposed legislation to attract medical professionals to rural and underserved regions of the state.

For his part, Sanders said getting students into medical school in the first place should be a priority.

"We have to have a concerted effort to build a pipeline as early as high school and elementary school to prepare students for careers," he said. "The challenge is really about helping students be prepared for college and subsequently medical school."

And perhaps there is cause for hope. Both Hispanic and African-American enrollees at medical schools rose in 2014, which also saw the highest number of people attending medical school on record.

Matt Hansen has written and edited for a series of online magazines, newspapers, and major marketing campaigns. He is currently active in press freedom and safety research with Global Journalist Security.

-

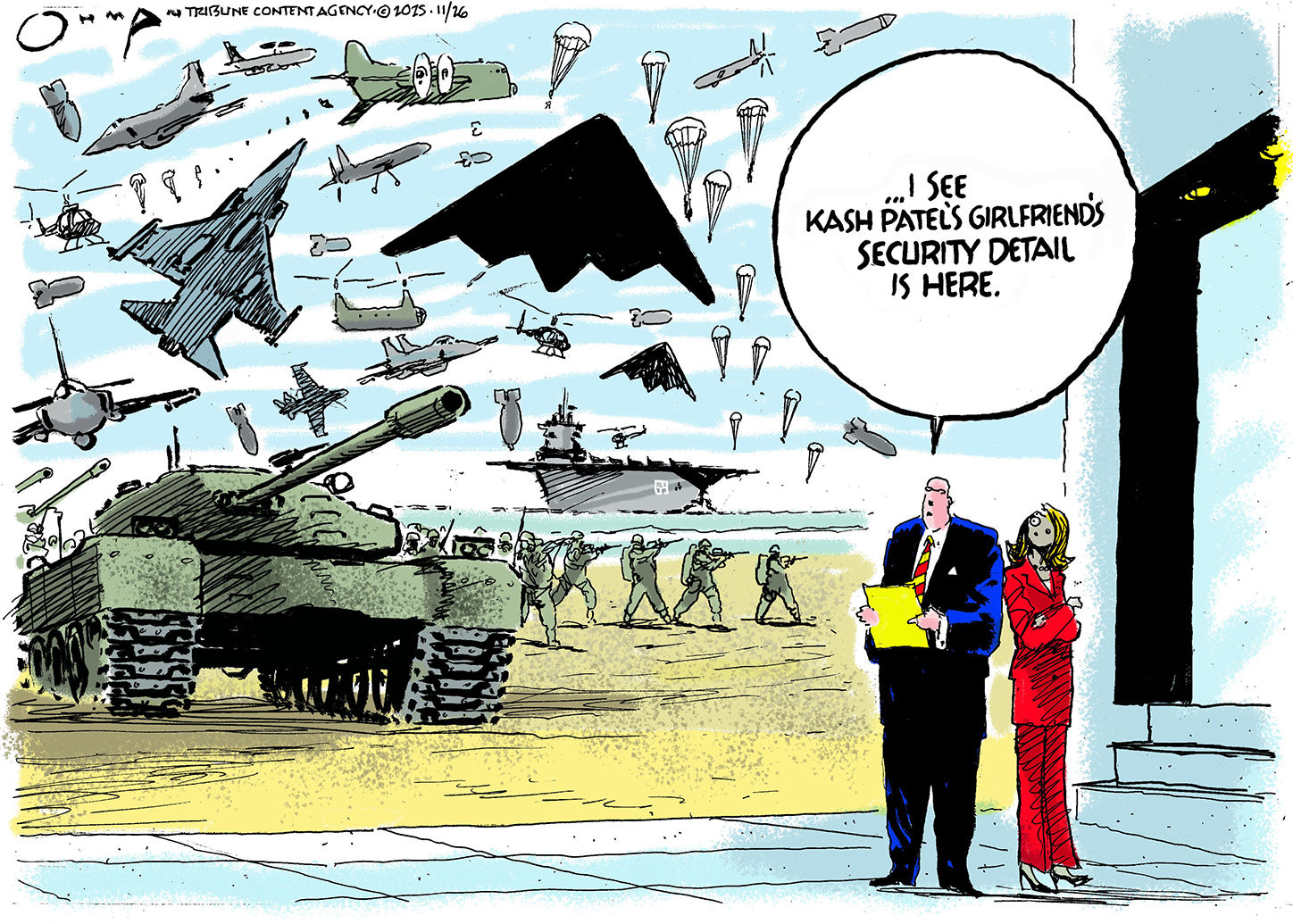

Political cartoons for November 29

Political cartoons for November 29Cartoons Saturday's political cartoons include Kash Patel's travel perks, believing in Congress, and more

-

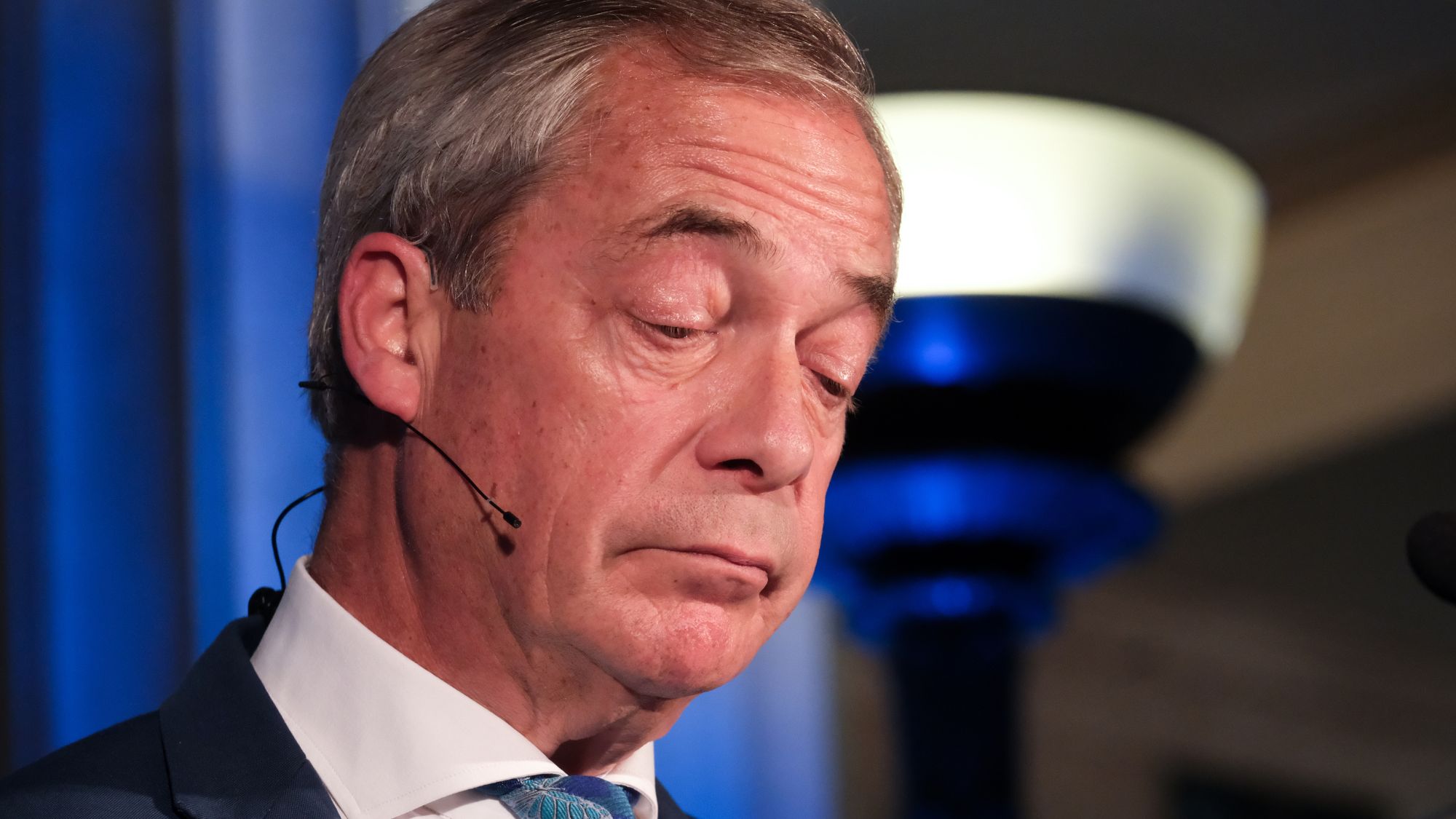

Nigel Farage: was he a teenage racist?

Nigel Farage: was he a teenage racist?Talking Point Farage’s denials have been ‘slippery’, but should claims from Reform leader’s schooldays be on the news agenda?

-

Pushing for peace: is Trump appeasing Moscow?

Pushing for peace: is Trump appeasing Moscow?In Depth European leaders succeeded in bringing themselves in from the cold and softening Moscow’s terms, but Kyiv still faces an unenviable choice

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration