The simple tool that could've prevented Greece's economic catastrophe

When it comes to bailouts, the European Central Bank isn't the only game in town

There's a story about the Greek economic crisis that everybody agrees on, even if they disagree about what to do.

Following the global 2008 economic collapse, Greece was hit by both a recession and the discovery that one of its former governments had effectively hoodwinked the international financial markets, hiding the true scale of its debt load. Those markets then abandoned Greece, and because it was on the euro, it couldn't exit the crisis by simply printing a lot of its own currency. That left Greece dependent on a bailout from its European brethren, which they offered only on the condition of strict austerity measures, plunging Greece into a grinding unemployment crisis.

Now, some people think Greece needs to suck it up and accept Europe's terms. Others (like me) say the sane and compassionate thing to do would be to bail out Greece full-stop, and bracket off reforming its fiscal behavior until after its economy has recovered. But everyone commenting on the whole debacle agrees that the above story is basically what happened.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But according to J.W. Mason, an economics professor at John Jay College, that narrative leaves out a crucial detail.

It's called the TARGET system — or TARGET2, as Europe is now on the second iteration of the setup.

While the eurozone is generally understood as a transnational monetary union, with the euro as its currency, the European Central Bank (ECB) is not the only central bank within it. Every European country still has its own central bank.

"All these national central banks still exist, and they do almost all the daily work of central banking the same way they always have,” Mason said in an interview.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The TARGET2 system allows this particularly decentralized form of centralized banking to function. For example, before the crisis, private German banks had been lending to private Spanish banks, which had been lending to Spanish property developers. When the 2008 collapse hit, a lot of those development loans went belly up. So the private Spanish banks turned to Spain's central bank for aid. The Spanish central bank decided to help them out, and this decision then set off a cascade of automatic balancing moves through the TARGET2 system: The Spanish central bank took on a liability on the ECB’s balance sheet, while Germany's central bank took on an asset. Meanwhile, Germany's private banks took an a balancing asset at the German central bank.

In other words, the original financial trade between the private German and Spanish banks — an asset on the German accounts, a liability on the Spanish ones — was rerouted into a series of trades through the TARGET2 system to keep the trades from going south.

Crucially, any national central bank in any European country can set off this mechanism. A large amount of Greece's public debt is held by its private banks, and the central bank of Greece could have bailed out those banks when the country's economy collapsed and it became apparent that public debt was not going to be paid back. But the ECB, the Greek central bank, and the rest of Europe's central banking system just…chose not to.

"There are no rules that say, because of the possibility of a Greek default on sovereign debt, ECB must cut off its assistance," Mason said.

"If the central bank of Greece was willing to lend to the national banks of Greece, that would automatically generate the flows from the rest of Europe," he continued. "They aren't willing to do that. The choice has been made that Greek banks aren't credit-worthy because they have too much Greek sovereign debt on their books… The ECB has instructed the bank of Greece not to lend to the Greek banks on a sufficient scale."

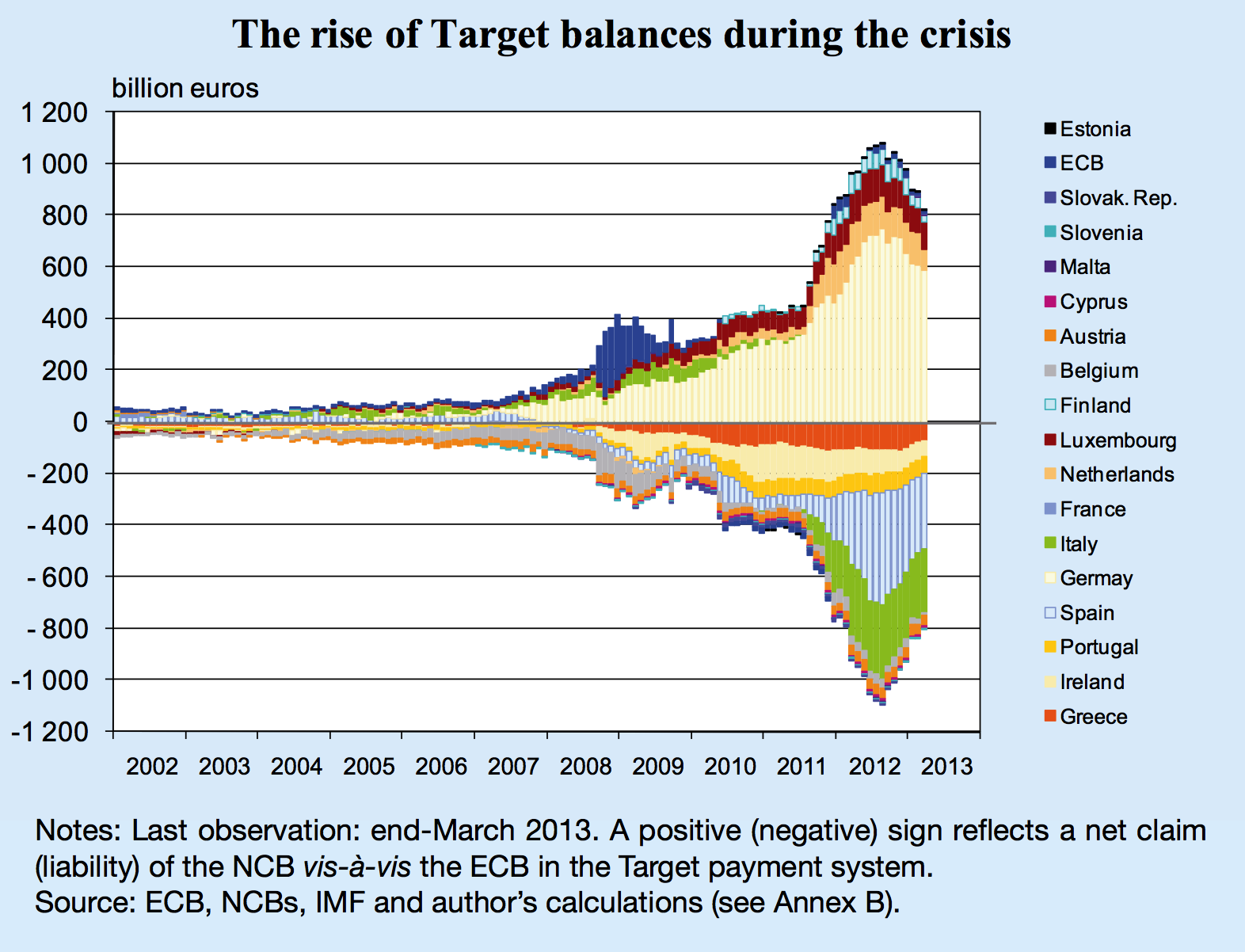

But this, according to Mason, was brazenly a political choice, as opposed to one driven by economic necessity. Probably the clearest evidence for this argument is the list of countries that were helped by TARGET2. Over the course of the European economic crisis, Greece was far from its biggest beneficiary. Spain, Italy, and Ireland all received far larger inflows (the negative balances on the bar graph below):

(Graph courtesy of Target Balances and the Crisis in the Euro Area, 2013, by Philippine Cour-Thimann.)

By 2011, yields on Irish and Portuguese debt had managed to spike to between 12 and 16 percent. Spain and Italy touched 7 percent shortly thereafter. Debt compounding at those rates over an extended period of time would've been truly unsustainable. Why didn't they go the way of Greece? "Because in 2012 Mario Draghi [president of the ECB at the time] took the deliberate decision to intervene in support of the sovereign debt of these countries," Mason said.

Because the ECB and the system of central banks control the supply of euros — just like the Federal Reserve controls the supply of U.S. dollars — there is essentially no ceiling on the TARGET2 system's ability to provide this kind of support. The only real limit is how much new money the European economy can absorb without inflation going through the roof. And given the enormous amount of unemployment in Europe's periphery countries, it can absorb a lot.

"You have people saying in the same breath, Europe is not threatened by a Greek default because ECB is permitted to do whatever it will take to support the financial institutions in the rest of the euro area," Mason explained. "At the same time [they're] saying Greece must get to the point where it's no longer dependent on extraordinary support to continue functioning within the system.

"The inconsistency sort of stares you in the face once you start paying attention to it.”

The funny thing is that many critics — including yours truly — have laid primary blame for the Greek debacle at the feet of a poorly designed currency union. If a set of countries is going to have a single currency, it should also have a single fiscal policy to move money around to prevent these sorts of catastrophic economic imbalances from occurring. The European countries, in this reading, are rather like the U.S. states, except without the support of any national federal budget.

Mason allowed that might still be the best approach for the eurozone. That kind of mechanism for spreading money between the countries would be more transparent and (ostensibly) more accountable to direct democratic control than the central banking system. But the currency union as it stands was actually more intelligently designed than this critique allows. TARGET2 is "a system that really kind of works," Mason said.

"They have the tools. They've used the tools very successfully in all these other countries. And they've made the choice not to do so in Greece."

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

Why is Trump threatening defense firms?

Why is Trump threatening defense firms?Talking Points CEO pay and stock buybacks will be restricted

-

How Utah became a media focal point

How Utah became a media focal pointIn Depth From #MomTok to reality TV gems, Utah has emerged as a media powerhouse

-

‘The security implications are harder still to dismiss’

‘The security implications are harder still to dismiss’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy