How Trump spent the war years

While John McCain was being tortured, The Donald lived large

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

IT WAS THE spring of 1968, and Donald Trump had it good. He was 21 years old and handsome, with a full head of hair. He'd avoided the Vietnam War draft on his way to earning an Ivy League degree. He was fond of fancy dinners, beautiful women, and outrageous clubs.

Most important, he had a job in his father's real estate company and a brain bursting with moneymaking ideas that would make him a billionaire.

"When I graduated from college, I had a net worth of perhaps $200,000," he said in his 1987 autobiography Trump: The Art of the Deal, written with Tony Schwartz. (That's about $1.4 million in 2015 dollars.) "I had my eye on Manhattan."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

More than 8,000 miles away, John McCain sat in a tiny, squalid North Vietnamese prison cell. The Navy pilot's body was broken from a plane crash, starvation, botched operations, and months of torture.

The stark contrast in their fortunes was thrown into sharp relief this month when Trump belittled McCain during a campaign speech in Iowa. "He's not a war hero," Trump said of McCain. "He's a war hero because he was captured. I like people that weren't captured."

Trump's comments drew scorn from his fellow Republican presidential contenders. But The Donald didn't back down. "When I left the room, it was a total standing ovation," he told ABC News in reference to his already infamous Iowa speech. "It was wonderful to see. Nobody was insulted."

In fact, a lot of people were insulted.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"John McCain is a hero, a man of grit and guts and character personified," Secretary of State John F. Kerry said in a statement. "He served and bled and endured unspeakable acts of torture. His captors broke his bones, but they couldn't break his spirit, which is why he refused early release when he had the chance. That's heroism, pure and simple, and it is unimpeachable."

If Trump doesn't think that that's heroic, then what, exactly, is admirable in his eyes? And what was he doing while McCain was locked up in the infamous prison that POWs sarcastically dubbed the Hanoi Hilton?

The answer reveals deep divides in the two men's lives and claims to leadership. They may similarly embrace free enterprise, but when it comes to character, the two men could hardly be more different.

McCAIN FAMOUSLY FOLLOWED his father and grandfather — both admirals — into the Navy. "My grandfather was a naval aviator, my father a submariner," he wrote in his autobiography, Faith of My Fathers. "They were my first heroes, and earning their respect has been the most lasting ambition of my life."

Growing up in Queens, Trump's role models were more…theatrical. "Two of the people I admired most and who I kind of studied for the way they did things were the great Flo Ziegfeld, the Broadway producer, and Bill Zeckendorf, the builder," he told The New York Times in 1984. "They created glamour, and the pageantry, the elegance, the joy they brought to what they did was magnificent."

McCain grew up in a military household. Trump grew up in a home dominated by his hard-charging, penny-pinching businessman father.

McCain enlisted in the Navy in 1958. Around the same time, Trump was sent to the New York Military Academy to straighten him out after some youthful transgressions. "He was a pretty rough fellow when he was small," his father told the Times in 1983.

Despite a successful stint at the military school, Trump doesn't seem to have been eager to enlist. It was 1964, and the Vietnam War was escalating.

He considered going to film school in California. Instead, he attended Fordham University for two years before transferring to the University of Pennsylvania, where he took economics courses at its famed Wharton School. (According to a book by Gwenda Blair, Trump was allowed to transfer into the Ivy League school because of family connections and has exaggerated his performance at Penn.)

During his time in school, Trump received four student deferments from the draft. As Trump was avoiding the war, McCain was about to become one of its most high-profile casualties.

The lieutenant commander had been flying for months, conducting targeted strikes on North Vietnam. He had already been injured in an aircraft carrier fire that killed 134 fellow sailors. And he had already made a name for himself as a pilot.

On Oct. 25, 1967, McCain had destroyed two enemy MiG fighter planes parked on a runway outside Hanoi. He begged to go out the next day too. But as he flew into Hanoi again on Oct. 26, his jet's warning lights began to flash.

"I was on my 23rd mission, flying right over the heart of Hanoi in a dive at about 4,500 feet, when a Russian missile the size of a telephone pole came up — the sky was full of them — and blew the right wing off my Skyhawk dive bomber," he wrote in a 1973 account of his ordeal. "It went into an inverted, almost straight-down spin. I pulled the ejection handle, and was knocked unconscious by the force of the ejection."

McCain regained consciousness when his parachute landed him in a lake. The explosion had shattered both arms and one of his legs. With 50 pounds of gear on him and one good limb, he struggled to swim to the surface.

North Vietnamese dragged him to shore. They stripped him to his underwear and began "hollering and screaming and cursing and spitting and kicking at me."

"One of them slammed a rifle butt down on my shoulder, and smashed it pretty badly," he wrote. "Another stuck a bayonet in my foot. The mob was really getting uptight." He was interrogated for four days, losing consciousness as his captors tried to beat information out of him. But he refused.

As the voluble Trump was already making a name for himself sweet-talking deals for his dad's real estate developing company, McCain was clamming up in his filthy prison. And as Trump drove around Manhattan in his father's limo, McCain was refusing to mention his dad for fear of handing valuable intelligence to the enemy.

McCain might have died from his injuries had the North Vietnamese not found out on their own that his father was an admiral. They moved him to a hospital and performed several botched operations on him. They sliced his knee ligaments by accident and couldn't manage to set his bones.

Trump, meanwhile, was taking Manhattan by storm. He had already made a small fortune working for his father during college.

In his autobiography, Trump describes those early years as fraught with danger. "This was not a world I found very attractive," he wrote in Trump: The Art of the Deal. "I'd just graduated from Wharton, and suddenly here I was in a scene that was violent at worst and unpleasant at best."

The danger? Collecting rent.

"One of the first tricks I learned was that you never stand in front of someone's door when you knock. Instead you stand by the wall and reach over to knock," Trump wrote of collecting for his father, who owned low-income housing blocks. "If you stand to the side, the only thing exposed to danger is your hand."

"There were tenants who'd throw their garbage out the window, because it was easier than putting it in the incinerator," he wrote in horror.

MEANWHILE, McCAIN LANGUISHED in a genuine hell. When he wasn't being tortured — several times his interrogators rebroke his mended bones — he was battling everything from dysentery to hemorrhoids. The prisoner of war survived on watery soup and scraps of bread. He saw several fellow prisoners beaten to death, yet McCain refused to sign the confession that would have granted him a speedy release.

Trump, meanwhile, was living large. He ate in New York City's finest restaurants and hit clubs with beautiful women. "The turning point came in 1971, when I decided to rent a Manhattan apartment," he wrote. "It was a studio, in a building on Third Avenue and 75th Street, and it looked out on the water tank in the court of the adjacent building…. I was a kid from Queens who worked in Brooklyn, and suddenly I had an apartment on the Upper East Side…I got to know all the good properties. I became a city guy instead of a kid from the boroughs. As far as I was concerned, I had the best of all worlds. I was young, and I had a lot of energy." That energy went into signing his first real estate deals — and into partying.

"One of the first things I did was join Le Club, which at the time was the hottest club in the city and perhaps the most exclusive — like Studio 54 at its height," he wrote. "Its membership included some of the most successful men and the most beautiful women in the world. It was the sort of place where you were likely to see a wealthy 75-year-old guy walk in with three blondes from Sweden."

I was so good-looking, Trump said, that the club manager "was worried that I might be tempted to try to steal other men's wives. He asked me to promise that I wouldn't."

Several years later, Trump was frequenting "Studio 54 in the disco's heyday and he said he thought it was paradise," Timothy O'Brien wrote in TrumpNation: The Art of Being the Donald. "His prowling gear at the time included a burgundy suit with matching patent-leather shoes."

As Trump made plans to buy and refurbish bankrupt hotels, McCain was staving off death in Hoa Lo Prison. And as McCain continued to refuse special treatment, Trump actively courted it.

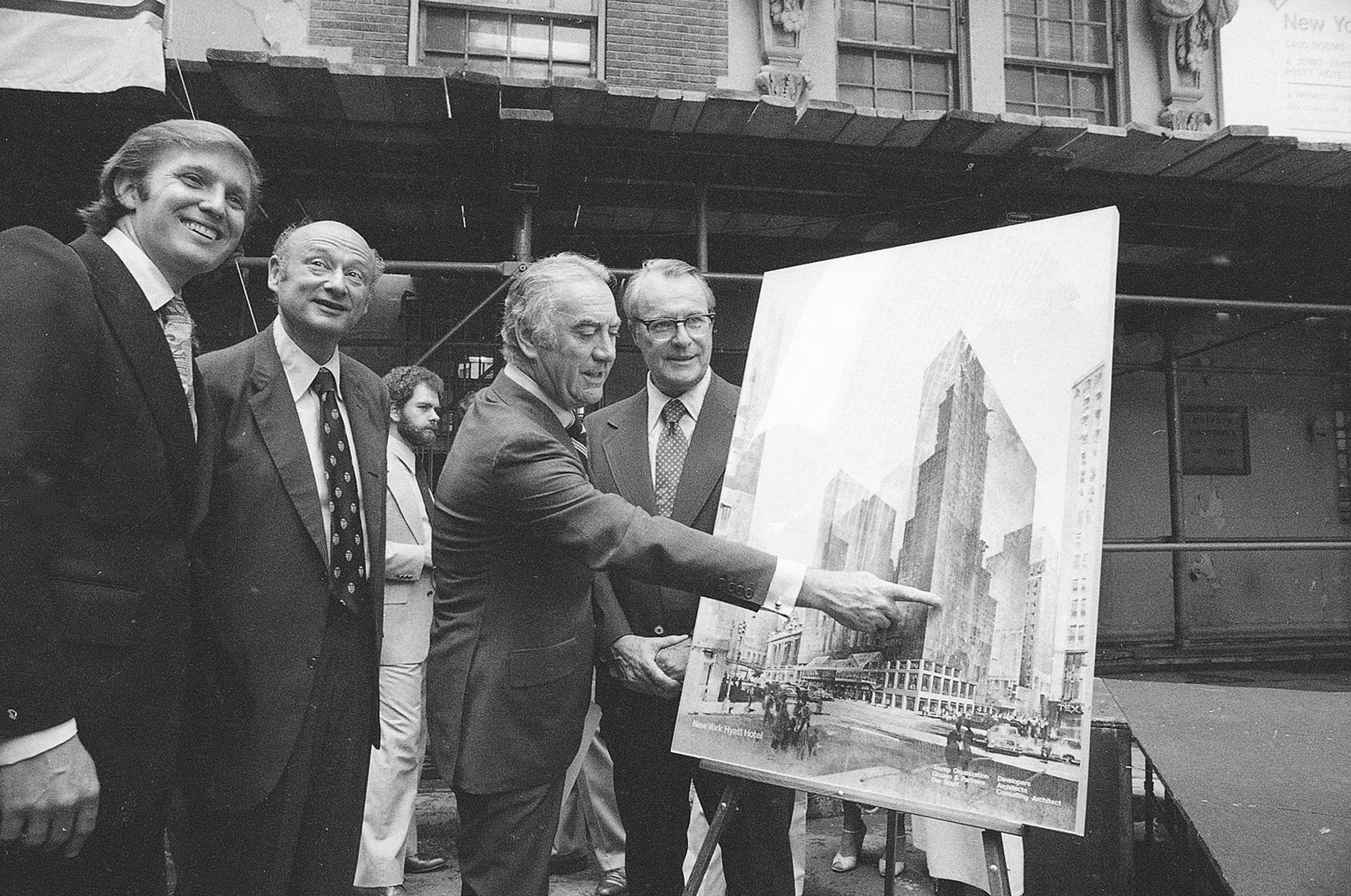

"The other thing I promoted was our relationship with politicians, such as Abraham Beame," who was elected mayor of New York in 1973, he wrote in Trump. "Like all developers, my father and I contributed money to Beame, and to other politicians. The simple fact is that contributing money to politicians is very standard and accepted for a New York City developer."

McCain refused to meet with most visitors for fear of being used as a puppet by the North Vietnamese. But back in the United States, Trump was only too eager to manipulate the press.

"At one point, when I was hyping my plans to the press but in reality getting nowhere, a big New York real estate guy told one of my close friends, 'Trump has a great line of s---, but where are the bricks and mortar?'" he wrote. "I remember being outraged when I heard that."

McCain was released on March 14, 1973. He arrived back in the United States a physically broken man, but also a hero. That word has yet to be applied to Trump.

That same year, the Department of Justice slapped the Trump Organization with a major discrimination suit for violating the Fair Housing Act. "The government contended that Trump Management had refused to rent or negotiate rentals 'because of race and color,'" according to The New York Times that year. "It also charged that the company had required different rental terms and conditions because of race and that it had misrepresented to blacks that apartments were not available."

Trump at first resisted signing a consent decree. He hired his friend, Roy Cohn, the lawyer and former right-hand man to Sen. Joseph McCarthy. "Mr. Trump said he would not sign such a decree because it would be unfair to his other tenants," the Times said. "He also said that if he allowed welfare clients into his apartments…there would be a massive fleeing from the city of not only our tenants but the communities as a whole." Ultimately, the company came to terms with the government.

Trump would weather the scandal, of course, and go on to build his fortune to its present-day tally of $4 billion. McCain, in contrast, received a Silver Star, Bronze Star, Purple Heart, and Distinguished Flying Cross. He would become a U.S. senator and run for president. Whether Trump can triumph where McCain came up short remains to be seen.

Excerpted from an article that originally appeared in The Washington Post. Reprinted with permission.

-

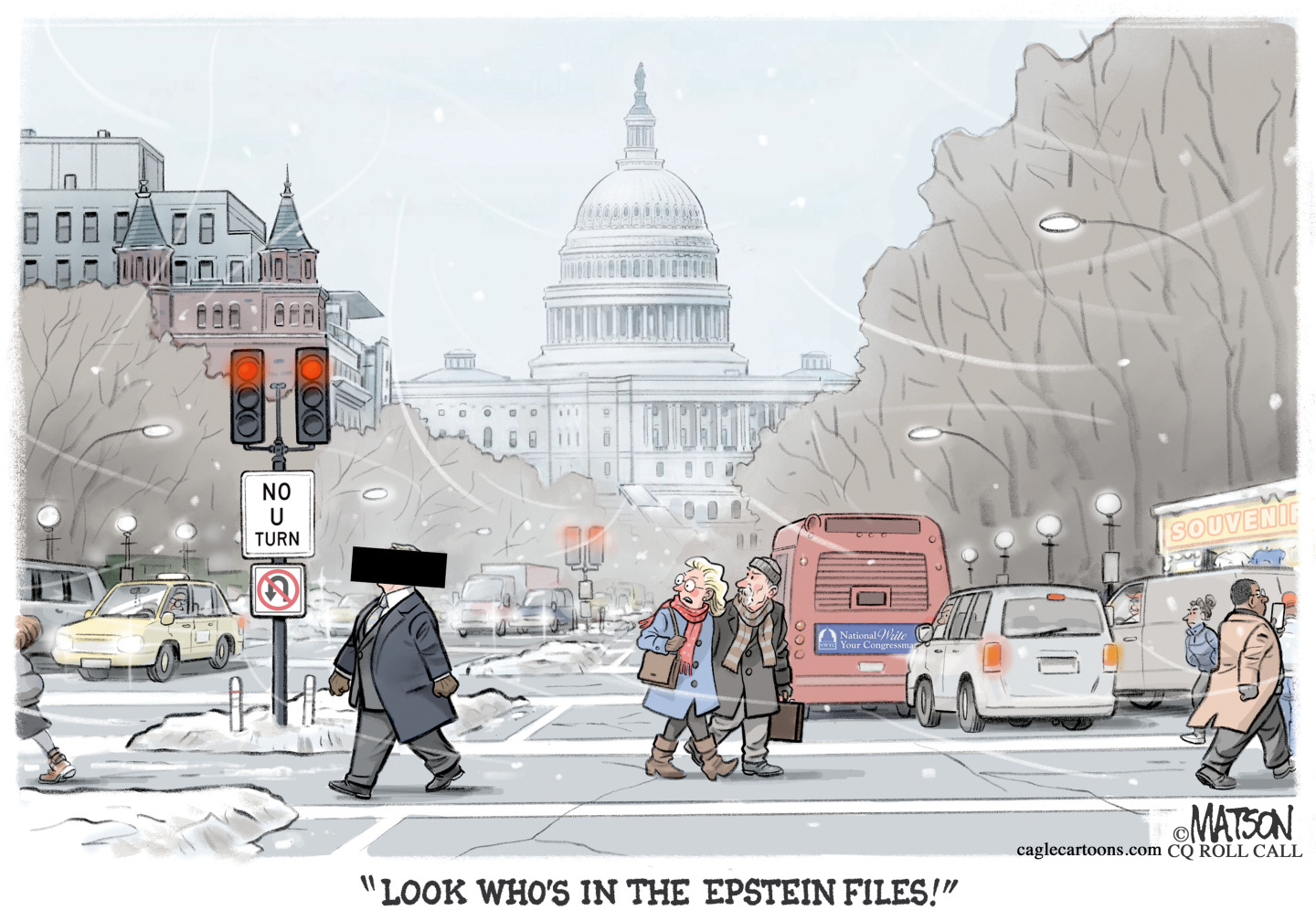

5 blacked out cartoons about the Epstein file redactions

5 blacked out cartoons about the Epstein file redactionsCartoons Artists take on hidden identities, a censored presidential seal, and more

-

How Democrats are turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonade

How Democrats are turning DOJ lemons into partisan lemonadeTODAY’S BIG QUESTION As the Trump administration continues to try — and fail — at indicting its political enemies, Democratic lawmakers have begun seizing the moment for themselves

-

ICE’s new targets post-Minnesota retreat

ICE’s new targets post-Minnesota retreatIn the Spotlight Several cities are reportedly on ICE’s list for immigration crackdowns

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred