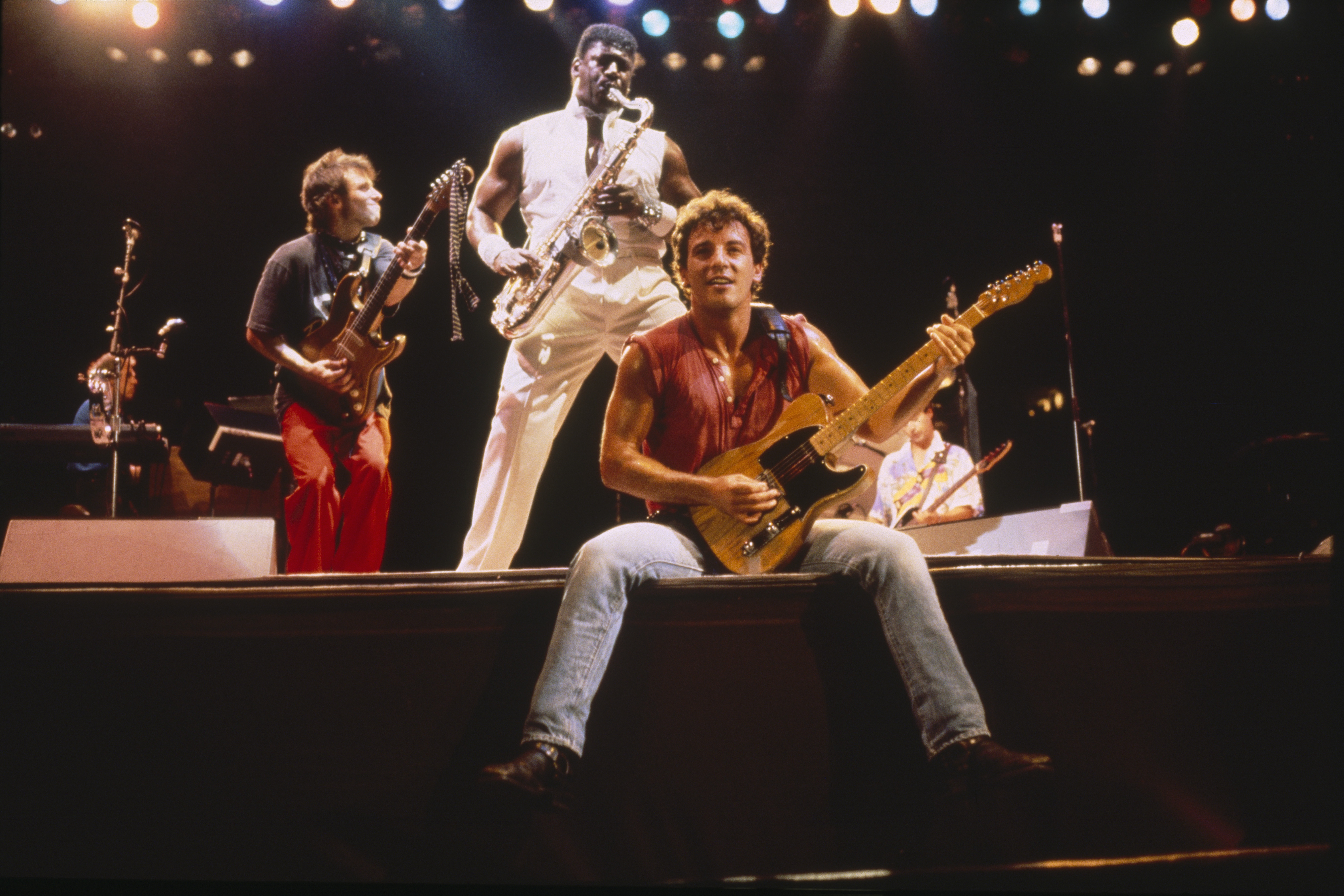

Born to Run at 40: A short history of the album that turned Bruce Springsteen into America's biggest rock star

A look back at the arduous process that led to Born to Run — and the pivotal moment when Springsteen almost scrapped it

Bruce Springsteen first heard the final mix of Born to Run — his third studio album — in a hotel in Kutztown, Pennsylvania, at the end of a grueling, 14-month recording session.

He hated it so much he hurled the tape into the pool. It was a make-or-break moment in the young musician's career.

The long, arduous process that eventually led to Born to Run began in 1974. The American music scene was changing, as rock made way for disco, punk, and the faint whispers of rap. Springsteen's first record, Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J., only sold 25,000 copies. His follow-up, The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle, didn't do much better. He was getting pressure from his label, Columbia, for a hit album that would show he had star potential, and Born to Run was his last chance.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"The leadership at Columbia had changed since Bruce signed and the new guys weren't fans," says Peter Ames Carlin, author of Springsteen's authorized biography Bruce, in an interview with The Week. "Noting the terrible sales of the first two records, they did throw down the gauntlet, only giving Bruce enough recording money to make a single, which would serve as his audition for making a third album."

Fortunately, the pressure from the Columbia executives was nothing compared to the pressure Springsteen put on himself. It took six months to record that one song — but when it was finished, Springsteen had the title track for Born to Run. "Once the Columbia folks heard that they were suddenly, and extremely, on board," says Carlin.

As for the rest of the album, Springsteen knew he had very specific sounds in his head. His challenge with his new album — the one he knew could save his career — was to make those sounds come alive on his new record. Springsteen wanted to replicate a recording technique known as "The Wall of Sound," which Phil Spector developed in the 1960s. It was a process in which multiple instruments played the same notes of a song in unison. Other instruments, such as string arrangements, were later overdubbed on top of those recordings, creating dense and complicated layers of sound.

But first, he'd need to rebuild the E Street Band from the ground up. After the arduous recording process of "Born to Run," pianist David Sancrous and drummer Ernest "Boom" Carter quit the band. After auditioning more than 60 people, pianist Roy Bittan and drummer Max Weinberg were hired as replacements.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Springsteen knew he had his title track, but he needed to fill the rest of the album with songs that were just as good. If the remaining members of the E Street Band thought the recording of "Born to Run" was exhausting, nothing would prepare them for the almost impossible expectations Springsteen had for the remaining seven tracks.

The recording session hit yet another roadblock at the now legendary 914 Sound Studio — an old garage converted into a recording studio by Brooks Arthur and Phil Ramone. The upstate New York studio, which has since been repurposed into the Blauvelt Auto Spa, was in disrepair, and the band quickly grew frustrated with the poor conditions. It was also a long drive back to New Jersey, where everyone lived. Some nights, after a full day of recording, the band would simply pitch tents and sleep in the backyard.

Springsteen pleaded with his manager, Mike Appel, to bring someone in to help oversee the recording process — someone with a fresh perspective who could help him translate the songs he imagined.

That man was Jon Landau, a Rolling Stone music critic who said, a year prior, that he "saw rock 'n roll future, and its name is Bruce Springsteen." Springsteen wanted Landau for a number of reasons, but his harsh but fair review of The Wild, the Innocent and the E Street Shuffle's production quality was the reason he was a perfect fit to tackle the recording problems of Born to Run.

The first thing Landau did was move the band to a state-of-the-art studio in Manhattan called the Record Plant. In their new studio, with Landau as a producer, Springsteen and the E Street Band could focus on the album without distraction. Working extensively with Britton on piano for songs like "Thunder Road," and Clarence "Big Man" Clemons on saxophone for "Jungleland," Springsteen annotated exactly what he envisioned, note-for-note, to his fellow musicians. For the sax solo on "Jungleland," Springsteen spent 16 hours working with Clemons, recording eight or nine tracks before cutting and re-cutting the sound.

Carlin — who spent time with Springsteen's friends, family and peers when writing Springsteen's biography — says the band members still recall the intensity of the Born to Run sessions. "Very tense and demanding, very stressful for everyone in the band," says Carlin. "But not nearly as stressful as it was in Bruce's head. Everything was on the line for him... he was either going to continue living his dream or get sent home with nothing but debt. So he agonized over individual notes, over the silences between the notes, and on and on. He needed to put every ounce of himself into getting it just exactly right — because from his perspective his entire life rested in the balance."

As management began booking tour dates for the album release, there was one glaring problem: The album wasn't finished. In fact, it wasn't complete until the first day of the tour, leaving the band only one day to rehearse. With sound mixing finally over, all they needed was Springsteen's approval. At the end of the long and extraordinarily trying process, studio engineer James Lovine handed Springsteen the finished album.

And that's when he threw it into the pool, and threatened to scrap the whole project.

How did Springsteen fail to recognize the brilliance of his own, now-legendary album when it was first placed into his hands? Carlin suspects it has something to do with the low quality of the material on which it was presented. "Acetates were notoriously lo-fi, and the portable hi-fi Bruce had with him was mostly plastic, not the stuff of faithful sonic reproduction," says Carlin. "So what Bruce heard sounded like… how do you say… shit. And given exhaustion and stress, he went a wee bit bonkers."

Fortunately, the moment of self-doubt was relatively short-lived. "Appel — still the manager of record and very close to Bruce — pretended to agree, starting a conversation about how they might move forward in another direction. Reverse psychology," says Carlin. "Then Jon Landau rushed down to talk sense into him. Bruce heard the wisdom. A couple of hours later, riding back to New York City with Appel, [he] shrugged and said, 'Then again, let's just let it ride.'"

Forty years to the day after its release, Born to Run is still considered Springsteen's masterpiece, perfectly capturing the voices of American youth and rebellion in the mid 1970s. It catapulted the 24-year-old into the kind of stardom he was so desperately afraid would pass him by — and that continues to pack sold-out stadiums today.

Charles Moss is a freelance writer based in Chattanooga, Tennessee. He's written for The Atlantic, Slate, Paste Magazine, The Oxford American, re:form and Tablet Magazine. Read more of his writing and hey, don't be shy. Friend him on Facebook or follow him on Twitter.

-

‘Jumping genes': How polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming Arctic

‘Jumping genes': How polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming ArcticUnder the radar The species is adapting to warmer temperatures

-

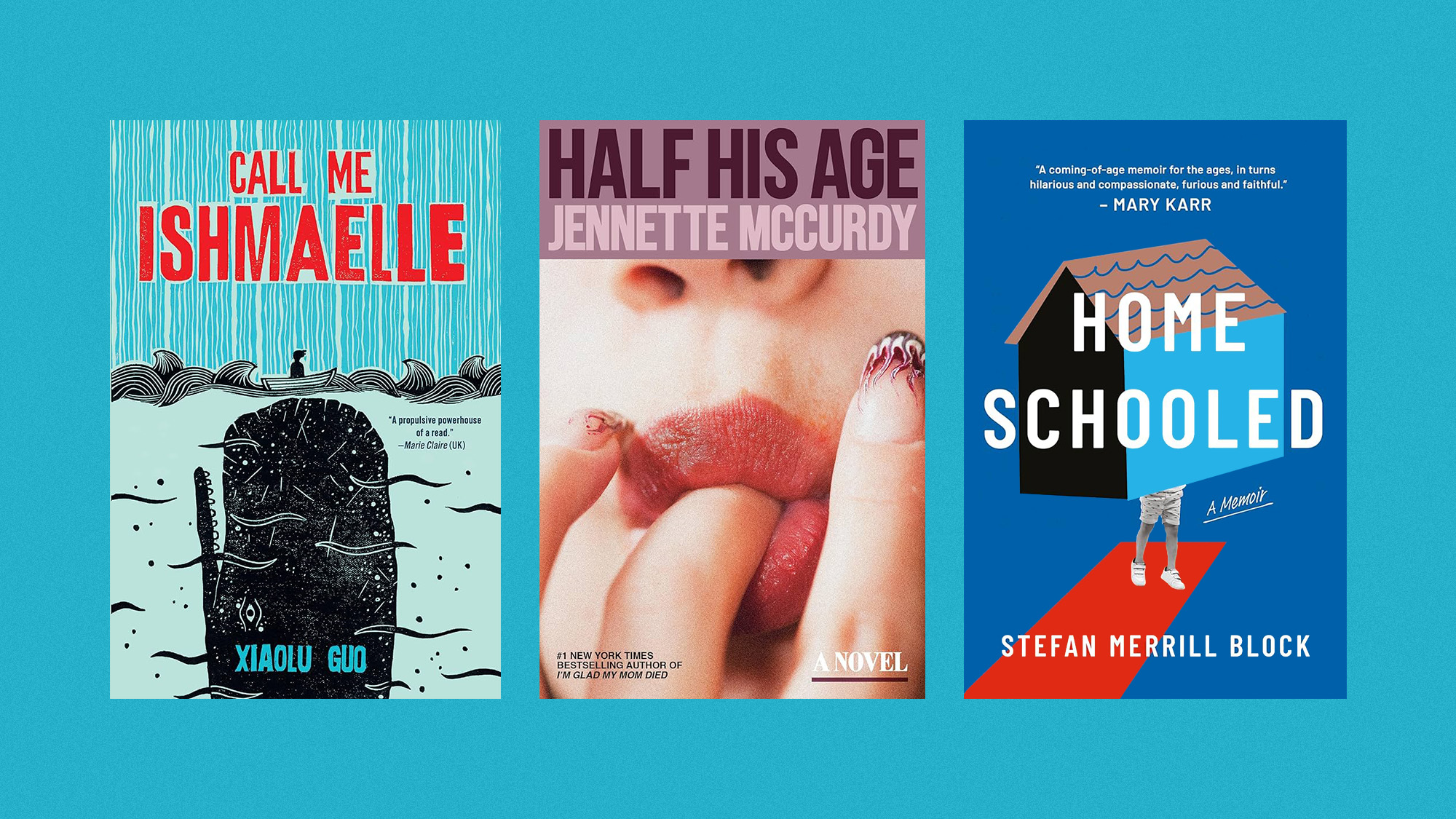

January’s books feature a revisioned classic, a homeschooler's memoir and a provocative thriller dramedy

January’s books feature a revisioned classic, a homeschooler's memoir and a provocative thriller dramedyThe Week Recommends This month’s new releases include ‘Call Me Ishmaelle’ by Xiaolu Guo, ‘Homeschooled: A Memoir’ by Stefan Merrill Block, ‘Anatomy of an Alibi’ by Ashley Elston and ‘Half His Age’ by Jennette McCurdy

-

Venezuela’s Trump-shaped power vacuum

Venezuela’s Trump-shaped power vacuumIN THE SPOTLIGHT The American abduction of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro has thrust South America’s biggest oil-producing state into uncharted geopolitical waters

-

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'The latest biography on the elusive tech mogul is causing a stir among critics

-

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!The Explainer Please allow us to reintroduce ourselves

-

The Oscars finale was a heartless disaster

The Oscars finale was a heartless disasterThe Explainer A calculated attempt at emotional manipulation goes very wrong

-

Most awkward awards show ever?

Most awkward awards show ever?The Explainer The best, worst, and most shocking moments from a chaotic Golden Globes

-

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. deal

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. dealThe Explainer Could what's terrible for theaters be good for creators?

-

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'The Explainer Move over, Sam Elliott and Morgan Freeman

-

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020feature So long, Oscar. Hello, Booker.

-

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortality

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortalityThe Explainer This film isn't about the pandemic. But it can help viewers confront their fears about death.