Aylan Kurdi, and the ethics of an image that shocked the world

When is it okay to publish a photo of a dead toddler?

If you are on any social media — or even if you read the newspaper or watch cable news — by now you've probably seen photographs of Aylan Kurdi, the 3-year-old boy whose body washed ashore on a beach in Turkey. He, his brother, and his mother died when their boat capsized on its way to a Greek island where the family would have been on European Union soil, far from the Syrian civil war they fled. The photos have been reproduced millions of times, on the cover of newspapers throughout the world and in untold numbers of Twitter and Facebook messages. And if you've seen the photos — perhaps the closeup of Aylan lying in the surf, or of the rescue worker cradling his lifeless body — you've probably also seen people debating whether news organizations should have published them, whether people should be passing them along, and whether you yourself should look at them.

This is a debate we have again and again, every time a crisis produces the kind of human misery and suffering you can capture in a still photograph. The images that are most dramatic often involve children. The emaciated girl seemingly stalked by a vulture during a famine in Sudan in 1993. The Iraqi boy who lost both his arms and most of his family to an American bomb in 2003. The firefighter holding a mortally wounded toddler after the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995. The young girl, burned by napalm, running naked down a Vietnam street in 1972. Almost as soon as we see them, we start asking ourselves questions about the images.

Things are different now than they were in those earlier cases, because social media have given all of us not just greater, faster access, but the ability to be publishers ourselves. The question isn't just whether news organizations should, using whatever journalistic standards they deem relevant, put them before us. We then have the opportunity to pass such images on, or not.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In Aylan's case, people immediately began not just resending the images of his body but repurposing them, making them into cartoons and photoshopping other elements into them. Some are meant to be accusations and calls to action, like the one placing his body on the floor of the United Nations; others are meant to be comforting, like the ones showing his soul rising to heaven.

And politics is never far from these decisions. Every time we have a war the government makes its own attempts to shield certain kinds of images from public view, lest the public feel the war's cost too acutely.

Beginning during the first Gulf War, photographers were barred from photographing the ceremonies at Dover Air Force base where coffins containing the bodies of those killed overseas return home. The Pentagon always said it was out of respect for the families' privacy, but this was plainly ridiculous, since no one seeing the pictures would ever know who was in the coffins (the Obama administration finally lifted the restrictions in 2009). And it isn't just the government — American news media have often tried to keep their coverage of our wars as far removed from the realities of death as possible.

Nowhere does that become more apparent than when it comes to the faces of those who have died. It's those faces — not the site of a severed limb or a pool of blood — that arouse the most squeamishness on the media's part, at least when it comes to Americans killed in action. Even in this case, I have seen some versions of the image of Aylan Kurdi with his face pixelated. That isn't done to protect his identity; we know exactly who he is. So why? Why is it that some editors believe it's appropriate and reasonable to see a 3-year-old lying dead on a beach if we can't look at the features of his face, but inappropriate and unreasonable if we could?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Without a face, he's an abstraction, an idea. See his face and he's a human being, unique and individual.

If you've heard someone say that we ought to be looking at the images of Aylan, it's because they're operating on the same assumption that the Pentagon did when it kept photographers from Dover. The assumption is that images are uniquely persuasive in ways that words aren't, that they not only affect us more viscerally and powerfully right in the moment, but that the impact might turn into some kind of action — opposing a war, or demanding that one's government take a different kind of action when confronting a humanitarian crisis.

And that's what those who pass on the images hope: you might ignore the story of the 71 migrants who died in a locked truck in Austria, but just try to ignore this.

Perhaps people won't be able to ignore it. There have been plenty of cases where the existence of photos did indeed make a difference in public opinion and the decisions that were made after their release (like the photos of prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib). On the other hand, Aylan was only one of thousands who have died this year alone trying to cross the Mediterranean and reach Europe (the UN puts the number at 2,500). The refugee crisis there is growing more intense by the day, and the countries of the EU are struggling to figure out how to deal with it; they'll come up with their own answers based on how their humanitarian impulses combine with their capabilities and their internal politics.

And the next time there's a war or a disaster or a refugee crisis, there will be another photo of a child, dead or suffering, that will capture the world's attention. Then another, and another after that.

Paul Waldman is a senior writer with The American Prospect magazine and a blogger for The Washington Post. His writing has appeared in dozens of newspapers, magazines, and web sites, and he is the author or co-author of four books on media and politics.

-

Israel’s E1 zone in the West Bank: the death of the two-state solution?

Israel’s E1 zone in the West Bank: the death of the two-state solution?The Explainer Controversial new settlement in occupied territories makes future Palestinian state unviable, critics claim

-

What the new Making Tax Digital rules mean

What the new Making Tax Digital rules meanThe Explainer A new system will be introduced from April to overhaul how untaxed income is reported to HMRC

-

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.Under the radar It is quickly melting away

-

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdown

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdownSpeed Read

-

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figures

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figuresSpeed Read

-

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancing

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancingSpeed Read

-

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens dead

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens deadSpeed Read

-

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictions

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictionsSpeed Read

-

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 dead

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 deadSpeed Read

-

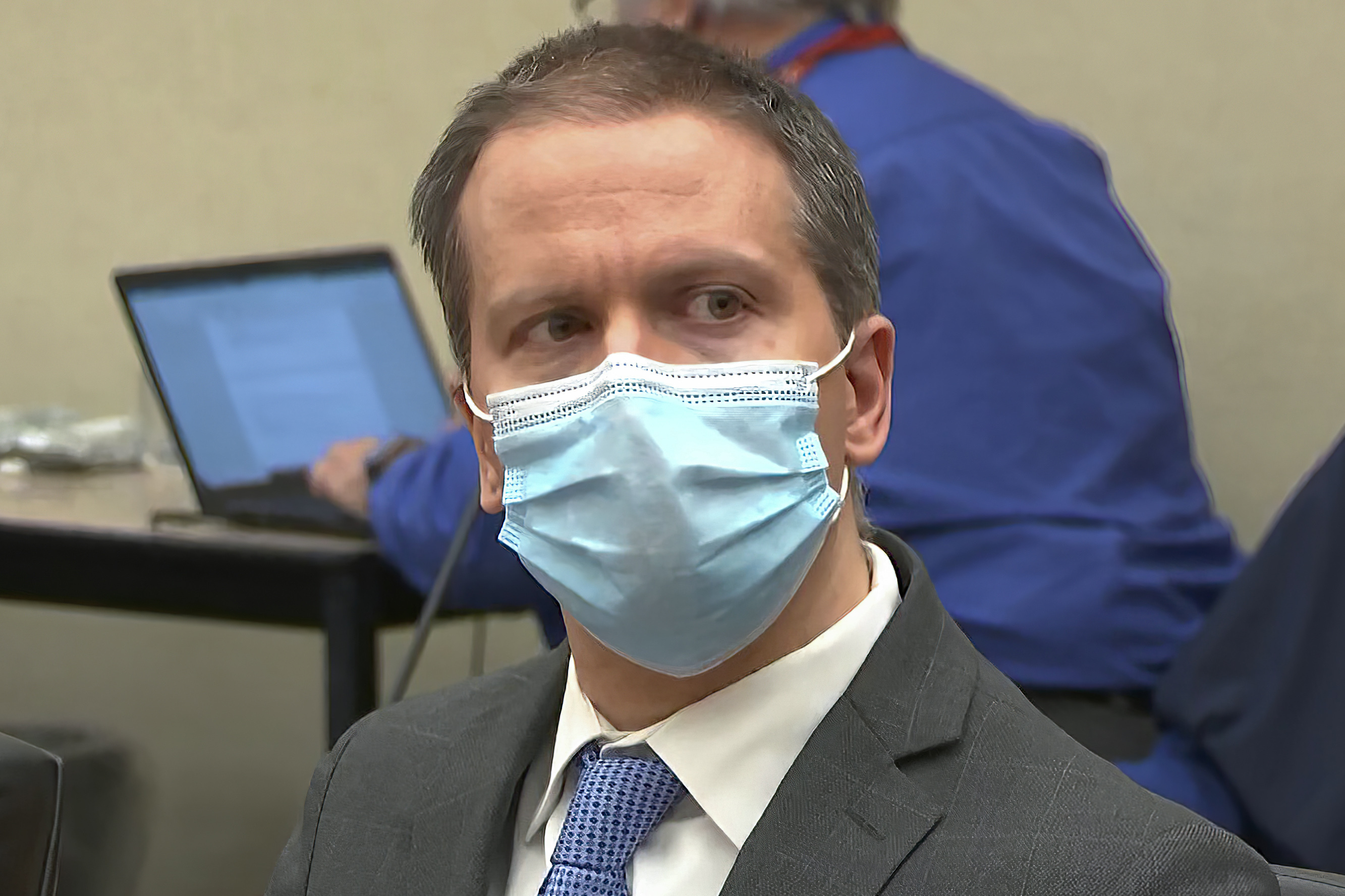

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trial

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trialSpeed Read

-

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapse

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapseSpeed Read