Men and mass murder: What gender tells us about America's epidemic of gun violence

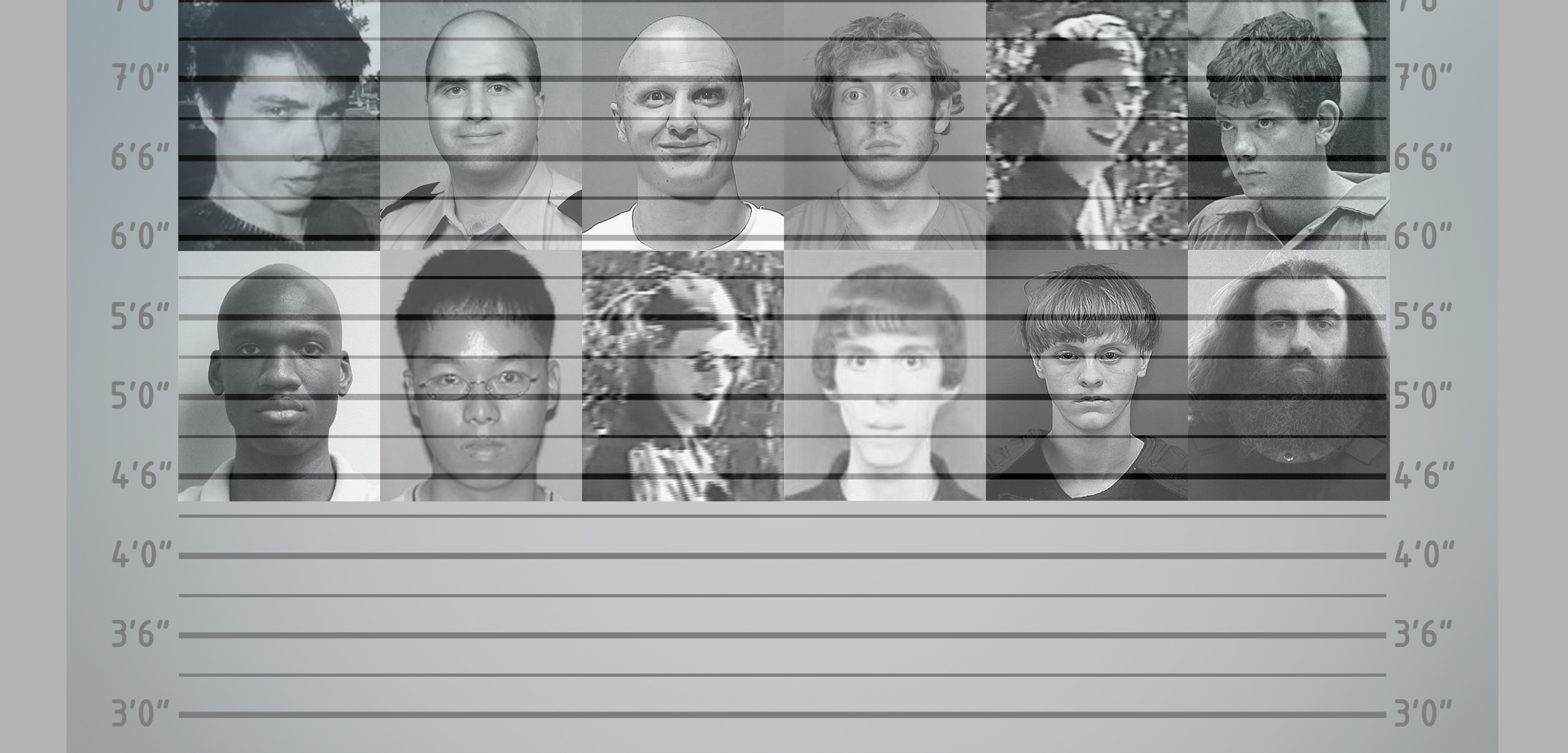

Nearly all mass murders are committed by men

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Another week (or day) in America, another mass shooting.

Another mass shooting, another flood of liberal attacks on gun culture, the Second Amendment, and the NRA. And another round of conservative pushback asserting some version of "guns don't kill people; people kill people." And another Barack Obama press conference railing at our failure to "do something" to stop the violence. And another Nicholas Kristof column about how we need to regulate guns like cars. And another flurry of calls to do a better job of responding to mental health problems.

And on and on and on. The specific victims and perpetrators change, of course, but the actions and reactions recur endlessly, as if all Americans were condemned to relive a single horrific trauma over and over again, with each faction in our national debate about gun violence playing their parts, never deviating from their scripts.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Not long ago, I made my own contribution to the conversation, expressing despair that anything can significantly change this horrifying facet of our national life and culture. There are already hundreds of millions of guns in circulation, and a program of mass confiscation would never be enacted. A not-insubstantial portion of the population ends up driven to use these deadly weapons to murder their fellow citizens, and it's not at all clear how anything can be done to keep someone from acting out in a homicidal-suicidal orgy of violence if he is hell-bent on doing so.

But realism (or fatalism) doesn't preclude trying to understand why it keeps happening. And as far as I'm concerned, the most disturbing (and also least discussed) aspect of America's epidemic of mass shootings is the fact that they are almost invariably committed by men.

Murder is an overwhelmingly male act, with the offender proving to be a man 90 percent of the time the person's gender is known. When it comes to mass shootings, the gender disparity is even greater, with something like 98 percent of them perpetrated by men.

We don't lack for explanations. To cite just a few: There's good, old-fashioned male aggression; the emotional immaturity of boys in comparison to girls; cultural norms that lead men to consider it unacceptable to ask for help, especially about mental and emotional problems; and the pervasiveness of graphically violent forms of entertainment, including video games that place the player in the position of the "shooter."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

All of these and other factors probably contribute in various ways to many shootings, with the decisive ones varying from case to case.

But there is an additional factor that doesn't get discussed as much as it should: the role of a distorted (but also extremely common) form of moral thinking in the psychology of men who commit mass murder.

I'm talking about the tendency of mass shooters to fixate on perceived injustices ranging from racial and sexual slights to various interpersonal and career-related failures. Shooters are murderously angry — and they're angry because they feel like the world has failed to give them the rewards they deserve.

The notion of desert stands close to the core of moral experience and belief. Most of us feel that those who are good deserve to triumph (or be rewarded) and those who are bad deserve to fail (or be punished). The American Dream of upward economic mobility, along with the postwar culture of meritocracy, presumes that our country is organized to make it happen: those who work hard will rise and those who do not will fall.

There's been a lot of recent talk about the breakdown of the American Dream, with leading public figures claiming that upward mobility has slowed considerably. Studies, meanwhile, appear to show that things may not be getting significantly worse, after all — although they also show that mobility in the U.S. lags behind what many other countries enjoy.

But the focus on change over time and international comparisons obscures the fact that to a considerable extent the American Dream has always been more of a myth than reality. Some people start off the race of life with enormous (natural and conventional) advantages over others. And for the biggest leaps up the economic ladder, luck always plays an indeterminate but substantial role.

Which means that deserving has very little, if anything, to do with the outcome.

It would be one thing if discovering this fact were an occasion for temporary disappointment or sadness. But that's not how many of us respond to evidence of the world's imperfect justice. We respond with anger. And when the injustices pile up, the anger can curdle into righteous indignation — into the conviction that the world itself is broken, that it's not merely failing to function as we've been taught it should, but that it's actually operating backwards, by systematically punishing those (like oneself) who deserve to succeed and rewarding those who deserve to fail.

Men and women both experience righteous indignation, of course. But there may be something specific about masculinity — perhaps its deep ties to irrational pride — that leads some men to experience a perceived injustice (and especially a string of them) as an excruciating personal humiliation that cries out not just for redress but for revenge. In this way, wounded pride provokes some men to lash out in a violent fury at their fellow human beings as a way of striking back at the intolerable injustice of the world.

By all means, let's continue to push for intelligent restrictions on guns. And for better ways to protect ourselves from them. And for better health services for the mentally ill.

But along with these well-intentioned efforts, it couldn't hurt to try and do a better job of teaching our kids — and especially our boys — that the world owes and guarantees them absolutely nothing. Setbacks and failures will always be painful. But they needn't be viewed as a sign that an existential promise has been betrayed — or treated as moral justification for a testosterone-fueled homicidal temper tantrum.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

Gunman kills 6, himself at Colorado Springs birthday party

Gunman kills 6, himself at Colorado Springs birthday partySpeed Read

-

Columbus police fatally shoots Ma'Khia Bryant, 16, quickly releases body-cam footage

Columbus police fatally shoots Ma'Khia Bryant, 16, quickly releases body-cam footageSpeed Read

-

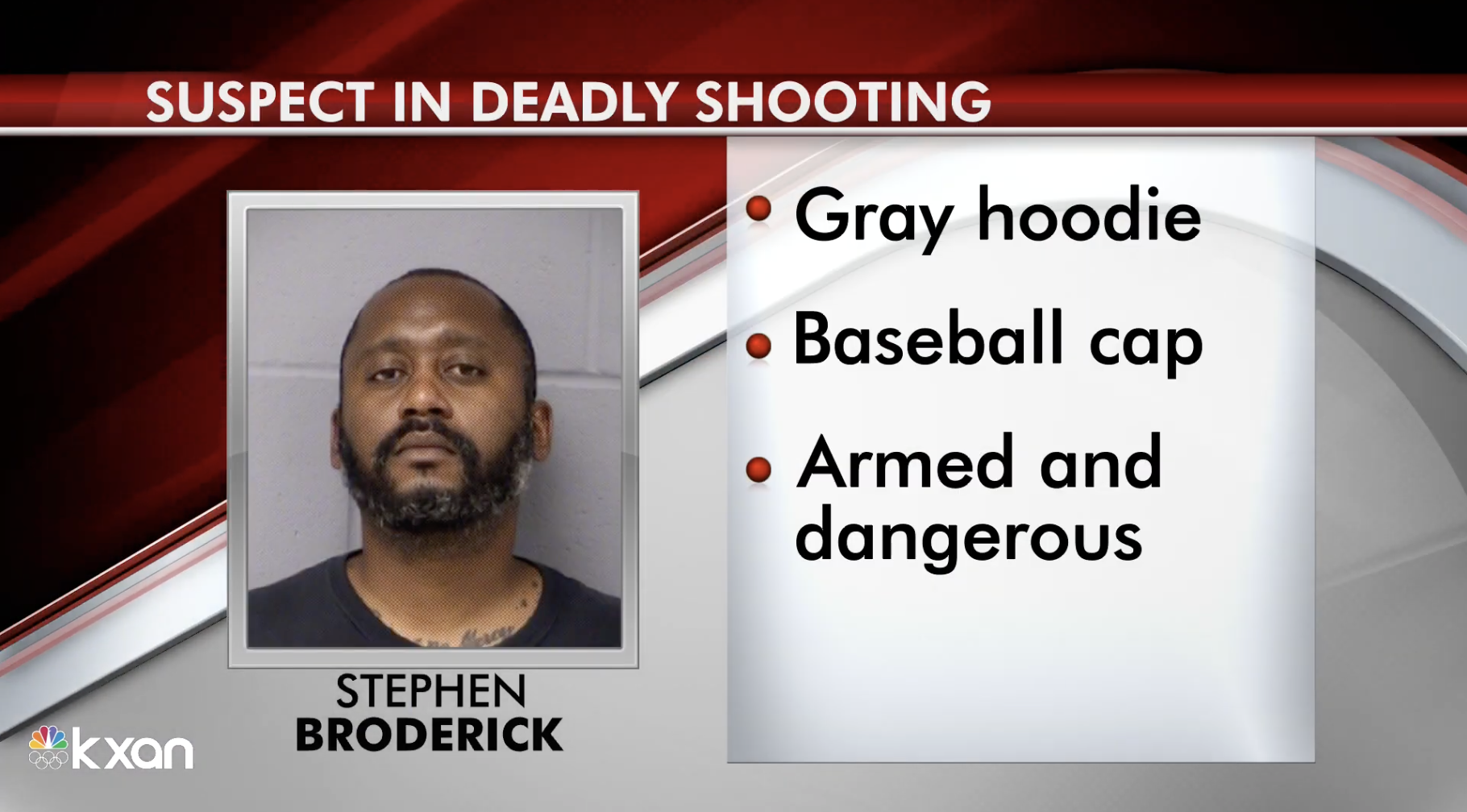

Austin police, feds searching for ex-sheriff's deputy accused of killing 3, in Sunday's 2nd mass shooting

Austin police, feds searching for ex-sheriff's deputy accused of killing 3, in Sunday's 2nd mass shootingSpeed Read

-

At least 8 dead in Indianapolis FedEx shooting

At least 8 dead in Indianapolis FedEx shootingSpeed Read

-

Scalise says GOP will 'take action' on Gaetz if DOJ moves ahead with 'formal' case

Scalise says GOP will 'take action' on Gaetz if DOJ moves ahead with 'formal' caseSpeed Read

-

Watchdog report: Capitol Police knew about potential for violence on Jan. 6, but held back

Watchdog report: Capitol Police knew about potential for violence on Jan. 6, but held backSpeed Read

-

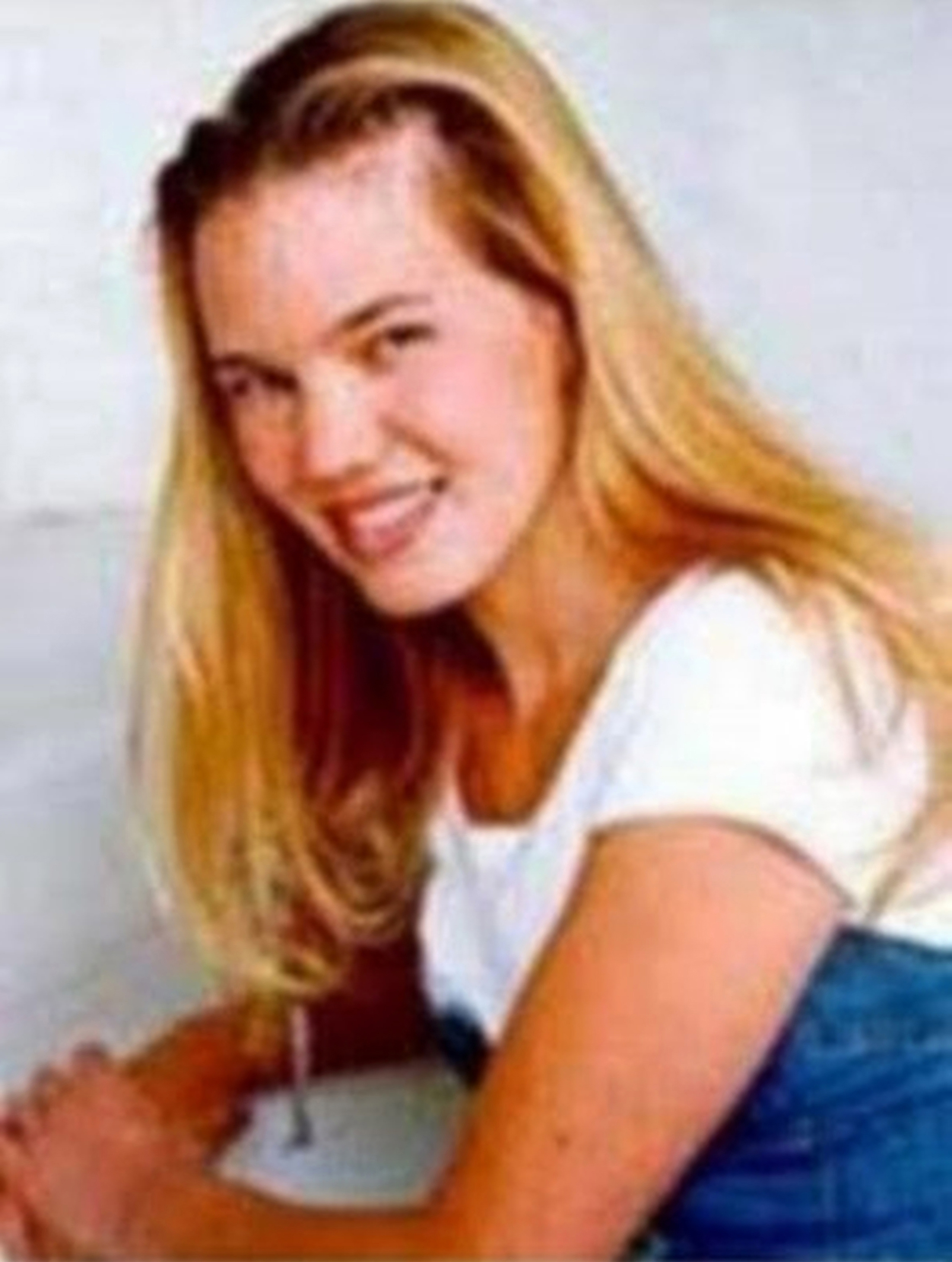

Former classmate arrested in 1996 disappearance of college student Kristin Smart

Former classmate arrested in 1996 disappearance of college student Kristin SmartSpeed Read

-

Report: Gaetz associate has been cooperating with federal investigators since last year

Report: Gaetz associate has been cooperating with federal investigators since last yearSpeed Read