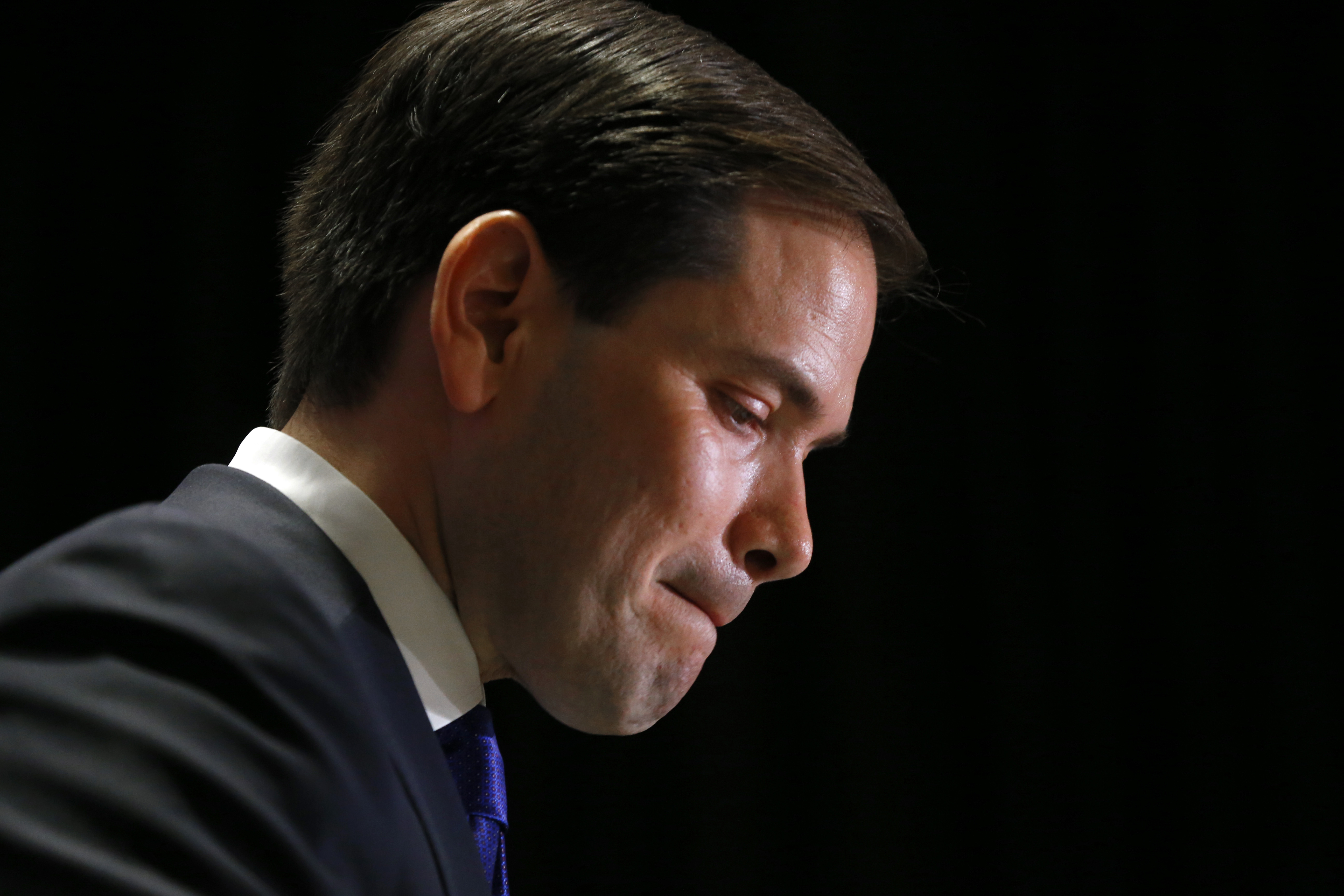

How fear and frustration crushed Marco Rubio

A requiem for a presidential candidate

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

"The time has come," Marco Rubio said when he announced his campaign for president last April, "for our generation to lead the way toward a new American century." It turned out that his generation may have to wait, and Rubio closed his campaign not by talking about a bright future that lays before us, but of a darkness that has overtaken his party. "I ask the American people, do not give in to the fear," he said on Tuesday night. "Do not give in to the frustration." But fear and frustration — in the form of Donald Trump — just crushed his dream.

Marco Rubio was supposed to be the Republican version of Barack Obama, a senator whose raw political talent could overcome his youth and relatively recent arrival in Washington and vault him to the presidency. But it turned out that Rubio's talents were not so overwhelming as they first appeared, and more importantly, that the party just wasn't interested in what he was selling.

That is to say, they weren't interested in Marco Rubio the man. His conservatism is every bit as doctrinaire as Ted Cruz's, even if he presents it in a package that comes across as much friendlier. But Rubio as an individual was supposed to be irresistible. He was the candidate of the Republican future, who could take conservatism and bring it to a changing America. The party of white people would pick a Latino as its champion, to open up the tent and broaden its appeal.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Again and again, Republican leaders and members of the media insisted that Rubio's moment was coming, any day now. He was just too appealing a candidate, at least on paper: He'd be a great contrast with Hillary Clinton; he was smart and articulate; he could go on Univision and Telemundo to appeal in his flawless Spanish to the voters the GOP wanted so desperately to reach. He even had an inspiring biographical story about his hard-working immigrant parents.

But somehow, Republican voters themselves never got the message that this was the guy they ought to be rallying around, no matter how many endorsements he got. Even though he enjoyed favorability ratings higher than any of the other candidates among his party's voters, Rubio seemed to be everyone's second or third choice.

So in trying to solve the problem, time and again Rubio adopted ideas and perspectives that seemed less his own than a poor impression of what he thought the voters felt. In one ad, he said, "This election is about the essence of America, about all of us who feel out of place in our own country." That may be a powerful feeling among many Republican voters, but the whole point about the young, Latino, bilingual senator was supposed to be that he didn't feel out of place, that he was a conservative who could speak to the new America.

But he kept trying. Among the candidates, Rubio was the most enthusiastic purveyor of the bizarre and paranoid notion that Barack Obama is intentionally attempting to destroy America — something often heard on conservative talk radio, but which never sounded quite sincere coming from Rubio. Then he got down in the gutter with Donald Trump, only to admit later that he regretted it, and that even his children felt embarrassed for him.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Rubio's story has really been that of the Republican Party itself. He came to Washington as a Tea Party favorite, then tried to achieve comprehensive immigration reform and was declared a traitor by the same people who had supported him. So he rejected that approach and decried illegal immigration, but by then he couldn't win back the base's trust. No matter what he did, he couldn't quite tune in to what Republican voters wanted.

In another year, it might have been different. But if Rubio was supposed to be the Republicans' answer to Obama, the president could have told him that in presidential politics, nothing is more important than timing. Rubio might have won in a different year — or he might be able to win some year in the future. But this year, he wasn't angry enough, he wasn't resentful enough, he wasn't enough of an outsider. And maybe he wasn't quite as adept a politician as everyone believed.

Rubio's failure reminds us that in the end, the candidate who looks good on paper still has to go out and convince the voters. And the candidate in whom party leaders and journalists see great potential might not be the one those voters want. Rubio was as conservative as anybody, but he couldn't channel and embody the disgruntlement, the disappointment, the alienation, and the outright rage that has gripped his party. His departure brings Donald Trump one step closer to being that party's nominee. So his plea for voters to rise above the fear and frustration is, at least during the primaries, likely to go unheeded.

Paul Waldman is a senior writer with The American Prospect magazine and a blogger for The Washington Post. His writing has appeared in dozens of newspapers, magazines, and web sites, and he is the author or co-author of four books on media and politics.

-

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’Feature An office doormat is stranded alone with her awful boss and a frazzled therapist turns amateur murder investigator

-

Movies to watch in February

Movies to watch in Februarythe week recommends Time travelers, multiverse hoppers and an Iraqi parable highlight this month’s offerings during the depths of winter

-

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance iceberg

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance icebergIN THE SPOTLIGHT Federal troops are increasingly turning to high-tech tracking tools that push the boundaries of personal privacy

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred