Why a $15 minimum wage won't unleash jobs Armageddon

The economic effects of a $15 minimum wage, explained

In a few years, it will be illegal to pay almost one-in-five American workers less than $15 an hour. That's thanks to two minimum wage laws just passed by New York and California, which will phase in the new threshold between now and 2022. This has lots of economists and pundits — even ostensibly liberal ones — all aflutter that these states are leaping dangerously into the unknown.

So are they? Recent work by economists at UC Berkeley suggests not.

In response to New York's proposal, the Berkeley economists built a simulation of how the $15 minimum wage would effect employment in the state. The model arguably applies to California too: Both states have big populations covering lots of different labor markets.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

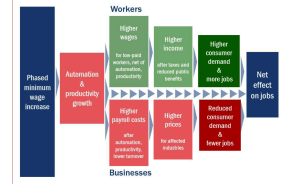

Now, when a business is required to raise its wages, it has a few options. First, it can try to increase its productivity. This allows them to sell the same amount of goods and services at the same price, but for a lower operating cost. The excess money can go into the wage increase. But once that option is tapped out, businesses generally have to hike prices. This reduces demand in the market, which lowers the overall amount of jobs. The UC Berkeley team classified this as the scale effect on employment.

Another reaction businesses have to rising wages is to hire less and invest in more equipment and automation. Again, that provides the same goods and services while keeping labor costs down by employing fewer people at the higher wage. This is the substitution effect on employment.

But the minimum wage is also a legal inducement for businesses and firms to shift how they distribute income: more to workers, less to management, owners, and/or shareholders. That means consumers in the market have more purchasing power, which means more aggregate demand, which means more jobs. That's the income effect on employment.

The Berkeley researchers mapped out all the different parts and how they interact:

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

(Graph courtesy of the UC Berkeley IRLE Minimum Wage Research Group.)

The UC Berkeley team then went through empirical studies of past minimum wage hikes to figure out values for all these different effects: To what degree do employers substitute automation for labor? To what degree does productivity increase? Etc. They picked the mid-range values pulled from the various studies and used those in the model.

They also noted a few things. For one, paying workers more reduces turnover (they leave for better pay less often) and improves worker morale. This increases productivity and saves employers money. Another thing, which surprised me, is that employers tend to avoid allowing wage hikes to eat into profits — they're much more likely to just hike prices.

After gaming out all these different factors, the economists' work concluded that the $15 minimum wage hike should increase employment in New York State — albeit just barely. The scale effect would lower jobs by 36,764, and the substitution effect would lower them by 41,590. But the income effect would increase them by 81,532, for a net job gain of 3,178.

That's just a 0.04 percent jump in projected employment for New York in mid-2021, which is obviously small. And given this is a projection, uncertainty could easily tip it over into modest negative territory. But that tiny jump in the raw number of jobs comes with a huge increase in living standards — a 23.4 percent jump in average wages for 3.16 million workers. "This improvement in living standards would greatly outweigh the small effect on employment," the economists wrote. "And the increase in wages would help reverse decades of wage declines for low-paid workers."

It's also worth noting that higher incomes lead to better health and well-being for both workers and their children — a positive side effect the study didn't account for.

Now, obviously there's some point at which a minimum wage would rise too high. Americans in the bottom 40 percent of the income distribution tend to save little or nothing, so income increases for them would go right into spending which means more demand and more jobs. But once households' income gets high enough, they start saving more. So after a certain point, minimum wage hikes will begin delivering smaller and smaller jobs gains, until the substitution and scale effects completely overwhelm it. The question is where that inflection point is.

In big cities like Los Angeles, San Francisco, and New York, unemployment tends to be lower (ranging from roughly 3 to 6 percent), so there's not that much slack in demand and job creation. This would seem like a big problem, since there wouldn't be as much room for wage increases to boost employment. But inequality and costs of living are also higher in these areas. Low-wage jobs in cities only pay slightly more than in cheaper markets, but unlike in smaller towns, there are also far more high-end jobs. That means there's enough rich people in LA, New York, and San Francisco to absorb price increases before they become a problem.

Most minimum wage skeptics worry about damage to the cheaper labor markets, though: the ones where a lot more workers are due for bigger pay gains, and where both overall wages and costs of living are lower than the big cities. But in California, for instance, unemployment is also considerably higher in these places — often topping 10 percent, versus the 5.7 percent for the whole state. So rising demand should lift many people out of unemployment before automation and rising prices become issues.

So maybe both big cities and more rural areas have lots of room to absorb a minimum wage hike, just in different ways: The big cities can take much higher price increases, and the small towns have a lot more idle workers who'll be lifted by the rising tide.

Point being, we need to do a better job of thinking through how a minimum wage actually impacts the economy — both at the specific level of an individual business and at the broader ecological level of an entire labor market. There are risks, but we need to state them and describe their contours. Because when we do, it starts to look like we may know what we're jumping into after all.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

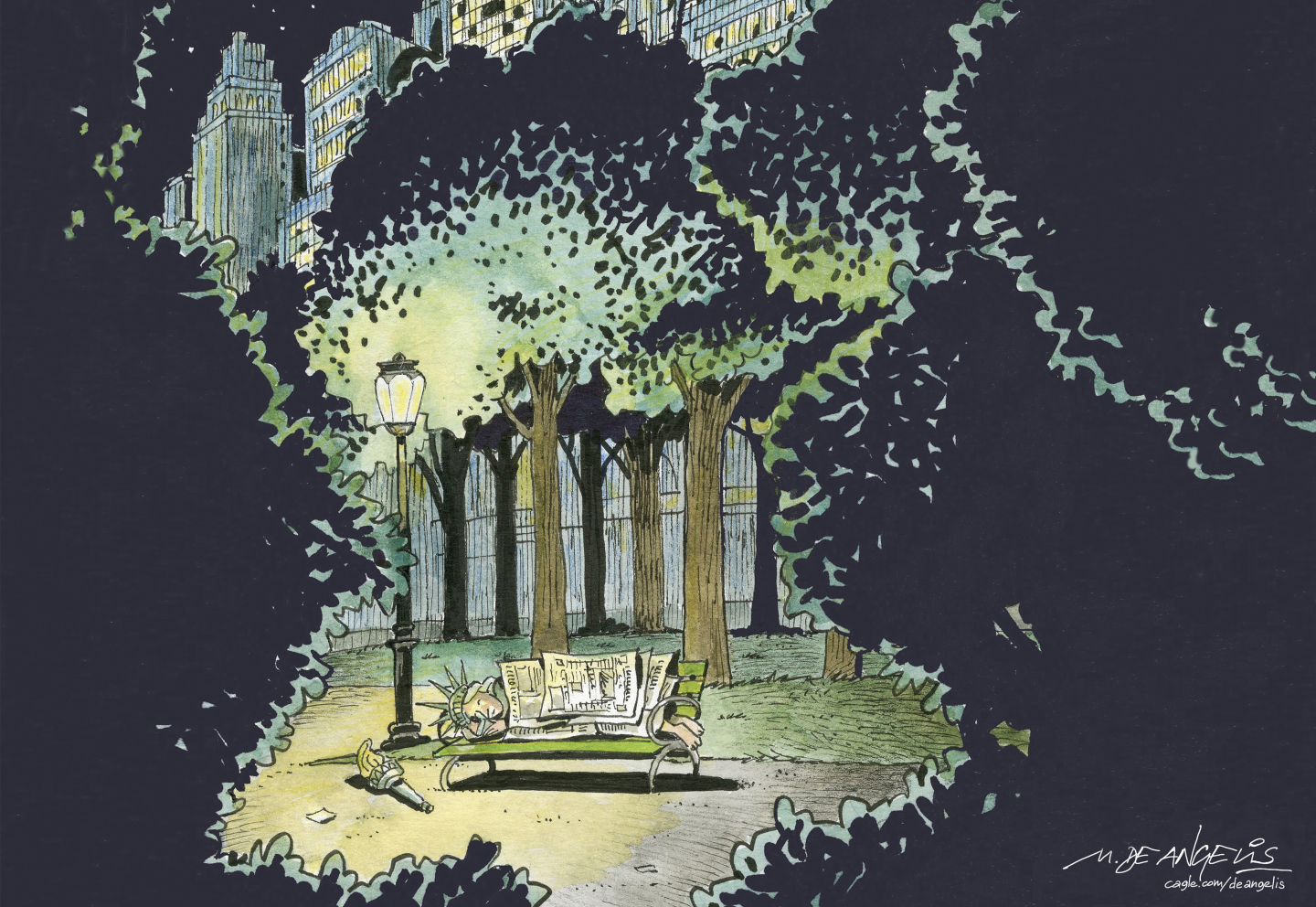

5 torch-carrying cartoons about Lady Liberty’s rough week

5 torch-carrying cartoons about Lady Liberty’s rough weekCartoons Artists take on dark nights, Lady Lineup, and more

-

Could Democrats lose the New Jersey governor’s race?

Could Democrats lose the New Jersey governor’s race?Today’s Big Question Democrat Mikie Sherrill stumbles against Republican Jack Ciattarelli

-

‘Porsche’s luxury credentials are now hanging by a thread’

‘Porsche’s luxury credentials are now hanging by a thread’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The pros and cons of noncompete agreements

The pros and cons of noncompete agreementsThe Explainer The FTC wants to ban companies from binding their employees with noncompete agreements. Who would this benefit, and who would it hurt?

-

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contraction

What experts are saying about the economy's surprise contractionThe Explainer The sharpest opinions on the debate from around the web

-

The death of cities was greatly exaggerated

The death of cities was greatly exaggeratedThe Explainer Why the pandemic predictions about urban flight were wrong

-

The housing crisis is here

The housing crisis is hereThe Explainer As the pandemic takes its toll, renters face eviction even as buyers are bidding higher

-

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkers

How to be an ally to marginalized coworkersThe Explainer Show up for your colleagues by showing that you see them and their struggles

-

What the stock market knows

What the stock market knowsThe Explainer Publicly traded companies are going to wallop small businesses

-

Can the government save small businesses?

Can the government save small businesses?The Explainer Many are fighting for a fair share of the coronavirus rescue package

-

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shock

How the oil crash could turn into a much bigger economic shockThe Explainer This could be a huge problem for the entire economy