The grotesque criminalization of poverty in America

Money bail is a vast moral abomination

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

If you are arrested for a serious crime, you're supposed to be taken to jail and booked. Then there's some sort of hearing, and if the judge doesn't think you will skip town or commit more crimes, you are either released on your own recognizance, or you post bail, and you are free until a pre-trial hearing. After that, you either go to trial, or plead guilty and accept punishment.

But for a great many people, this is not how it works. As a new report from the Prison Policy Initiative demonstrates, over one-third of people who go through the booking process end up staying in jail simply because they can't raise enough cash to post bail. For millions of Americans in 2016, poverty is effectively a crime.

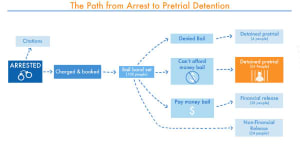

This flowchart lays out the basic reality for people who get booked. A very small minority (4 percent) are denied bail, while about a quarter are released without bail. Thirty-eight percent manage to make bail, while 34 percent can't scrape together the cash:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

(Courtesy Prison Policy Initiative)

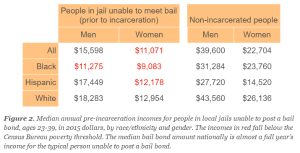

People who can't make bail (let's call them "bailed-in") make little money, with a median pre-jail income of $15,109 — less than half the median income for the general population. Unsurprisingly, African-Americans have it the worst, with the lowest median income and the largest difference between the bailed-in population and their non-incarcerated cohort:

(Courtesy Prison Policy Initiative)

This makes a complete mockery of the criminal justice system's pretense of fairness and impartiality. There are a dozen other ways it is rigged in favor of wealth and social status, of course, but most of these are more subtle and underhanded. Here there are people openly sitting in jail, being punished without conviction or a guilty plea, simply because they don't have enough money.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Jail is an absolutely horrible place. The living conditions are hellish, prisoners and guards are frequently abusive, and medical care is atrocious. Particularly for people who haven't been arrested before, being booked for the first time is so traumatic that suicide — typically within the first 24 to 48 hours — is the single leading cause of death in jails.

Jail is a big business, both for bail bondsman and for cash-strapped counties in the South (some of which are notorious for stopping out-of-state black people on any imaginable pretext so as to hold them up for bail money). Many court dockets, particularly in poor, populous locations, are completely swamped with cases without remotely enough resources to process everyone according to the rules of due process. One quick and easy shortcut is to load up the accused with as many charges as possible, demand a gigantic bail, and rely on fear and economic pressure to secure a guilty plea. (Some 97 percent of cases which are not dismissed are settled by plea bargaining.)

It's hard to say how many legally innocent people are jailed in this way. At any given moment, roughly 646,000 people are in American jails, but there is also tremendous churn in and out of the jail system — 11.4 million admissions in 2014 alone.

The fact that millions of these people probably sat in jail for lack of money is nothing less than a moral abomination.

Many if not most of the people who end up in jail have committed crimes, some of them violent. But a society's commitment to due process and the rule of law can be measured by how it treats its least sympathetic members. It's easy to endorse constitutional treatment for the drug-addicted daughter of middle-class parents. But accused murderers deserve the same exact consideration.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdown

'Once the best in the Middle East,' Beirut hospital pleads for fuel as it faces shutdownSpeed Read

-

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figures

Israeli airstrikes kill senior Hamas figuresSpeed Read

-

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancing

An anti-vax conspiracy theory is apparently making anti-maskers consider masking up, social distancingSpeed Read

-

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens dead

Fighting between Israel and Hamas intensifies, with dozens deadSpeed Read

-

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictions

United States shares 'serious concerns' with Israel over planned evictionsSpeed Read

-

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 dead

Police raid in Rio de Janeiro favela leaves at least 25 deadSpeed Read

-

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trial

Derek Chauvin's attorney files motion for new trialSpeed Read

-

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapse

At least 20 dead after Mexico City commuter train splits in overpass collapseSpeed Read