Why Britain should leave the EU

Instead of the EU frightening Britain about the consequences of Thursday's vote, the British people should make the EU know the consequences of its kludgy, overweening, snotty, and undemocratic form of government

Britain is not my country. But I sincerely hope that my British friends, former colleagues, and relations in Ireland vote to leave the European Union in the so-called "Brexit" vote on Thursday. Why? Because Britain is the only country large, powerful, and confident enough to give the EU the shock of recognition that could lead it to reform.

The "Remain" campaign will probably win in the end, a result that can largely be pinned on the serious strategy errors of the "Leave" campaign, which has been far too focused on immigration. Further, much of the Leave camp adopted the slogan "Take Control," which emphasizes all the responsibilities and duties of political sovereignty, but none of the fun or adventure of true independence. "Screw 'em" would have been a more appropriately 2016 slogan.

Regardless, Britain should leave — because the EU cannot possibly reform itself without real upheaval.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Europe is a tangled failure of undemocratic bureaucracy. The European Commission, which makes an alarming number of laws Britons must abide by (perhaps as much as 60 percent of them in recent years), is an unelected body. The European Parliament has no mechanism for repealing laws, no properly organized opposition at all. As many Leave campaigners never tire of pointing out, plenty of commissioners are chosen to serve only after they have been defeated in their own national elections. Men like Neil Kinnock lost successive elections in Britain, only to get a promotion to the European Commission.

At every level, the EU lacks the kinds of institutionalized opposition or checks on power that are the hard-won victories of the people in their national parliaments. You see it in the impotent European Parliament that acts as a rubber stamp for the Commission, or the unanswerable and supreme European Court of Justice. The history of the EU is a history of making countries vote repeatedly on treaties they have rejected until they accept them.

When the people of Greece elected a government to save them from the economic calamity that they could not escape for lack of their own currency and central bank, the Germans made an awful example of them. Many of the same people who want Remain to win now argued that it was atavistic for Britain to retain the pound. Has anything in the last decade of economic life in the EU made Britons regret retaining their own currency?

The Remainers say that Leave has campaigned on the fear of modernity, or of immigration. Even fear of capital-P Progress itself. For some, like the redoubtable Alex Massie, Leave amounts to "a howl against the realities of modern Britain; a desperate cry for a reversion to an imagined earlier age when the world was a simpler, and better, place. A revanchist cri de coeur. Britain has changed and many people dislike that."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Nevertheless, it has changed for the better. This is a grander, kinder, more relaxed and liberal country than it was half a century ago. If you doubt that, ask yourself whether you'd rather be a woman, a homosexual, or an immigrant now or in 1966? It shouldn't be a difficult question to answer. [The London Spectator]

Unfortunately, Massie is merely invoking the universal prejudice people have against their grandparents. We are so much more knowing than they are. But if there is any truth about what Massie says of Britain, it isn't the EU's doing. The same run of cliches could be said of almost any non-EU country, like Switzerland, or Canada. The EU still includes Catholic Poland, and the "revanchist" Victor Orban. Instead of an argument for Brussels' supremacy over Downing Street, Massie has made an argument for praising the universal culture being built by Hollywood in America, not the eurocrats.

The Remainers have fear, too. They fear the classes of people in Britain who were impoverished by the successive economic liberalizations under Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair. They fear Nigel Farage so much that they prefer political union with Victor Orban.

But I've always sensed that the biggest fear of Remainers is not expressly political. They never argue that the EU has democratic legitimacy — most admit it doesn't. They don't argue that British sovereignty is worth effacing. Instead, many Remainers simply invoke that sense of openness and possibility that presented itself to them as young people, the easy and inexpensive trips to Portugal, the education in Dublin, the destination wedding in northern Italy. Even nationalist-leaning euroskeptics, if they are under 40, understand that any hardening of European borders is as much a psychic trauma as a political event. Much of that enlarged sense of possibility is as much the product of ever-cheapening air travel, and the communications revolution, as it is of the Schengen arrangements.

But now those who first enjoyed the fruits and fission of the EU's free travel are discovering that it comes with serious costs. The cost is found in cracked home foundations leftover from Ireland's property boom, in the sunk costs your friend had in that dumb Bulgarian property idea, in the shattered Greek economy, in the economic sclerosis that has afflicted Spain, or left so many youth underemployed in France and Italy. It has a political cost in renewed populist nationalism — from Hungary to Poland, and possibly soon to France and Germany.

Britain, because it retained its currency, has the ability to escape. It has the ability to strike its own free-trade agreements with Canada or India without consulting Italian unions. Britain's economic and military might makes it a top-tier country apart from the EU. And its market is large and rich enough that Continental Europe will not be able to bring itself to really make Britain pay dearly for Brexit. French and German firms don't want to lose all their British national employees, and they certainly don't want to lose the British market.

Britain is not helpless the way Greece was helpless. Instead of the EU frightening Britain about the consequences of Thursday's vote, the British people should make the EU know the consequences of its kludgy, overweening, snotty, and undemocratic form of government. The rest of Europe may thank Britons in the end.

Michael Brendan Dougherty is senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is the founder and editor of The Slurve, a newsletter about baseball. His work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, ESPN Magazine, Slate and The American Conservative.

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

The Week contest: Post-surgery Spanish

The Week contest: Post-surgery SpanishPuzzles and Quizzes

-

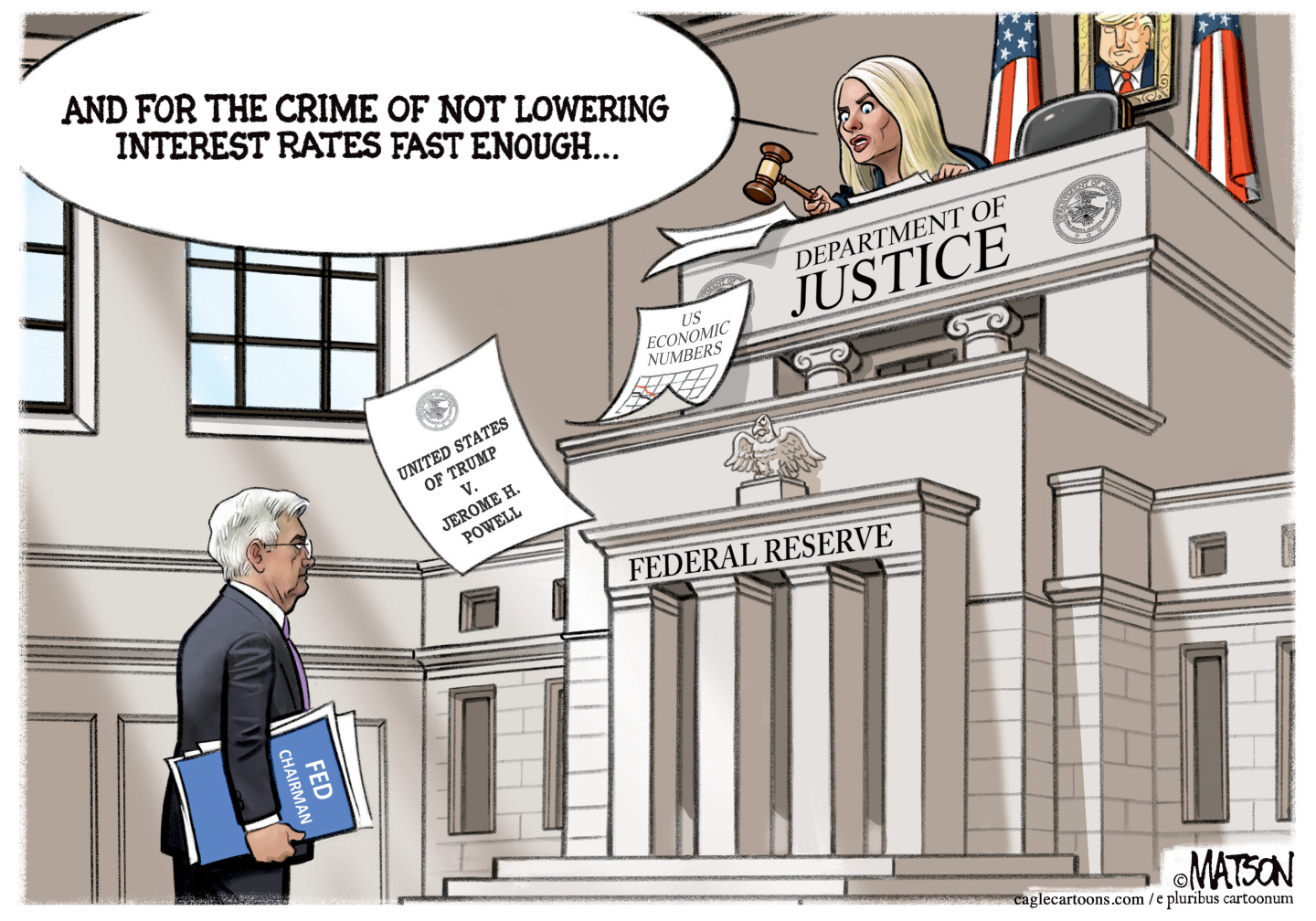

Political cartoons for January 14

Political cartoons for January 14Cartoons Wednesday’s political cartoons include Jerome Powell's rap sheet, holiday bill blues, and more

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult

-

Iran cuts internet as protests escalate

Iran cuts internet as protests escalateSpeed Reada Government buildings across the country have been set on fire

-

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by Russia

US nabs ‘shadow’ tanker claimed by RussiaSpeed Read The ship was one of two vessels seized by the US military

-

How Bulgaria’s government fell amid mass protests

How Bulgaria’s government fell amid mass protestsThe Explainer The country’s prime minister resigned as part of the fallout

-

Femicide: Italy’s newest crime

Femicide: Italy’s newest crimeThe Explainer Landmark law to criminalise murder of a woman as an ‘act of hatred’ or ‘subjugation’ but critics say Italy is still deeply patriarchal

-

Brazil’s Bolsonaro behind bars after appeals run out

Brazil’s Bolsonaro behind bars after appeals run outSpeed Read He will serve 27 years in prison

-

Americans traveling abroad face renewed criticism in the Trump era

Americans traveling abroad face renewed criticism in the Trump eraThe Explainer Some of Trump’s behavior has Americans being questioned

-

Nigeria confused by Trump invasion threat

Nigeria confused by Trump invasion threatSpeed Read Trump has claimed the country is persecuting Christians