Is it no longer 'the economy, stupid'?

Cultural issues seem to have superseded pocketbook concerns in this wild election

This bit of down-home political wisdom was at the heart of Bill Clinton's successful 1992 presidential campaign. And indeed, jobs, income, and living costs are awfully important to voters, if not paramount. Many election forecasting models center on economic variables.

So you'd think the state of the U.S. economy would go a long way toward explaining voter mood in 2016, particularly Donald Trump capturing the Republican nomination. But it's not so simple. A March analysis of GOP primary results by the Manhattan Institute's Scott Winship found Trump performed no better in states where voters said the economy was the biggest issue than in other states. Likewise, Mother Jones economics blogger Kevin Drum noted that Trump was actually doing slightly worse with economically anxious voters than with voters overall.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

If it's no longer "the economy, stupid," than what is it?

Maybe it's the culture. There is, after all, apparently deep Republican unease about America's transformation into a nation that is less white and less Christian. A recent Pew Research analysis found GOP voter attitudes about Trump are "strongly associated" with their views on "immigration, Islam, and racial diversity." And when looking at Trump's broader base of Republican support, conservative thinker Avik Roy reluctantly concluded "the gravitational center of the Republican Party is white nationalism," rather than, say, limited government or supply-side economics.

This theory of the party's collective racial and ethnic panic seems to explain a lot. Not so long ago, Republicans were outraged by Obama's big budget deficits, apologetic foreign policy, executive arrogance, and disdain for free enterprise. Now the party has just nominated someone who proposes an economic plan that would double the national debt, claims the U.S. lacks moral authority, would persecute political enemies in the media, and dismisses some 200 years of free-market economic thinking on trade.

Still, it's hard to ignore the macroeconomic environment in which this nativist, populist, Trumpist backlash is happening. And we probably shouldn't. In his 2005 book The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth, Harvard University economist Benjamin Friedman argued that the value of rising living standards is hardly limited to the cool stuff it provides us. Just as importantly, Friedman wrote, economic growth "more often than not fosters greater opportunity, tolerance of diversity, social mobility, commitment to fairness, and dedication to democracy."

In this view, the fast growth of the late 1950s and 1960s helped propel the Civil Rights movement, just as stagnation spurred the late 19th century populist era. It's not a perfect theory; Friedman concedes that Great Depression America "strengthened its commitment" to openness and tolerance, as typified by the New Deal. Of course, the 1930s still saw the emergence of populist politician Huey Long and the isolationist Charles Lindbergh. And it's at least suspicious that after the worst downturn since the Great Recession and the weakest recovery in American history, movements against openness, tolerance, and diversity again have momentum.

Then there's the populism of the inequality alarmists of the left, as represented by Team Feel-the-Bern. Yet high-end inequality is about the same as it was in 2000. When it did rise sharply in the 1990s, people seemed to care far less because pretty much everyone benefited from the strong economy. Households "of virtually every type experienced large, steady income gains, whether they were headed by men or women, by blacks, whites, or Hispanics, or by people with high school diplomas or college degrees," notes a 2015 Brookings study.

Economic growth and opportunity, broadly shared, still matter when it comes to having a nation, as President Ronald Reagan said in his final speech in office, "teeming with people of all kinds living in harmony and peace … [humming] with commerce and creativity." But the Trump campaign is focused on "law and order" — though not necessarily in that order — while the new Democratic platform has little to say about boosting growth through innovation-driven productivity gains.

Back in 2007, British Prime Minister Tony Blair said that the "real dividing line … in modern politics has less to do with traditional positions of right versus left, more to do today, with what I would call the modern choice, which is open versus closed."

But where is America and its politics today? A recent PRRI/Brookings survey found 58 percent of white Americans say "they are not comfortable being around immigrants who speak little or no English," 55 percent of all Americans believe "the American way of life needs to be protected against foreign influence," 52 percent say free trade agreements with other countries "are mostly harmful," and 43 percent say "immigrants are a burden on the country" including 65 percent of Republicans.

The shared prosperity of a dynamic economy may not be the only thing needed for a flourishing society of openness and opportunity, but it sure helps. Maybe this election is about "the culture, stupid." But don't forget about economic growth.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

James Pethokoukis is the DeWitt Wallace Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute where he runs the AEIdeas blog. He has also written for The New York Times, National Review, Commentary, The Weekly Standard, and other places.

-

5 cartoons about the TACO trade

5 cartoons about the TACO tradeCartoons Political cartoonists take on America's tariffs, Vladimir Putin waiting for taco Tuesday, and a new presidential seal

-

A city of culture in the high Andes

A city of culture in the high AndesThe Week Recommends Cuenca is a must-visit for those keen to see the 'real Ecuador'

-

The Chagos Islands: Starmer's 'lousy deal'

The Chagos Islands: Starmer's 'lousy deal'Talking Point The PM's adherence to 'legalism' has given Mauritius a 'gift from British taxpayers'

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are the billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are the billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration

-

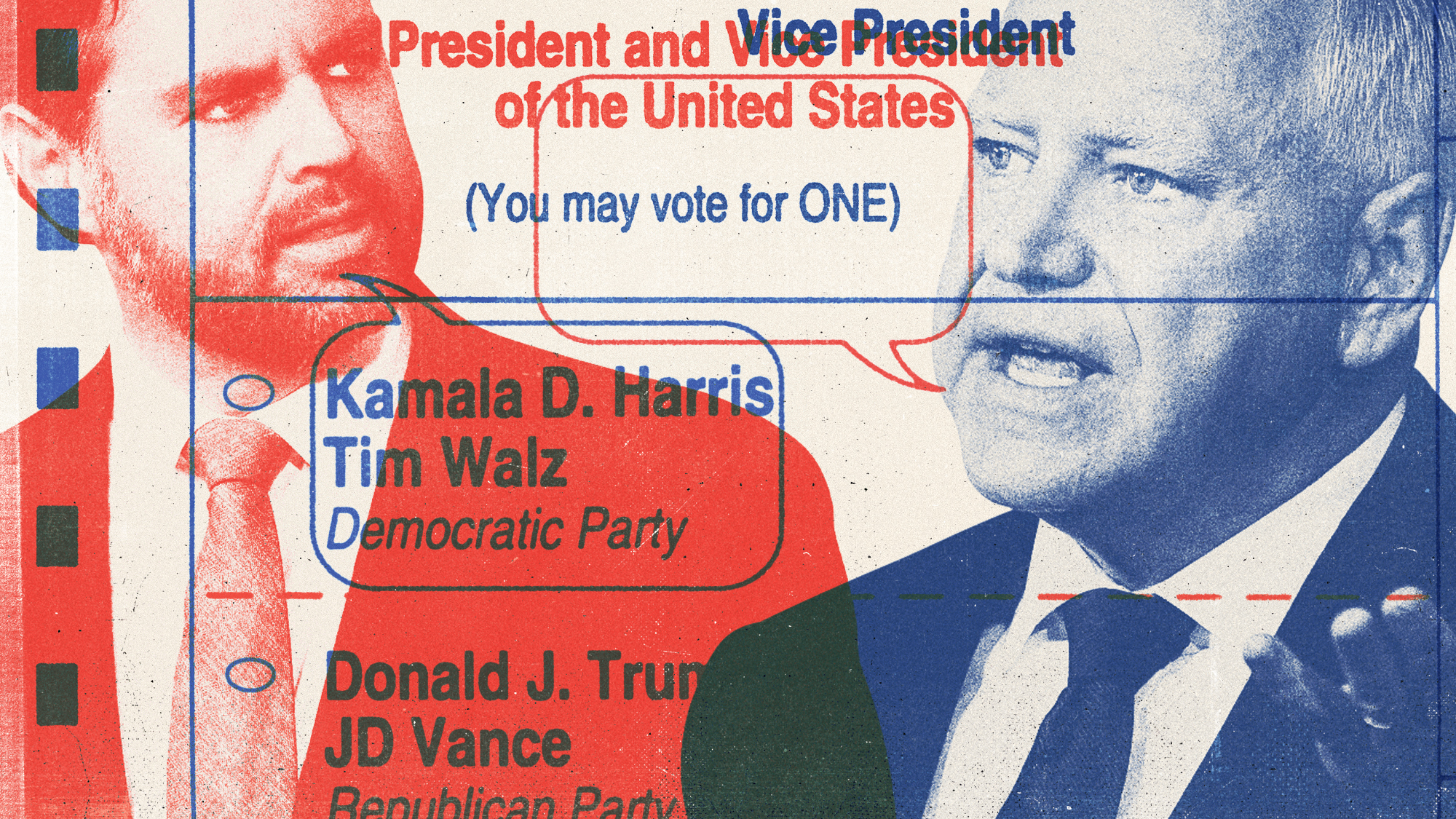

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event

-

The life and times of Kamala Harris

The life and times of Kamala HarrisThe Explainer The vice-president is narrowly leading the race to become the next US president. How did she get to where she is now?

-

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?Today's Big Question 'Diametrically opposed' candidates showed 'a lot of commonality' on some issues, but offered competing visions for America's future and democracy