Revenge of the ghostwriters

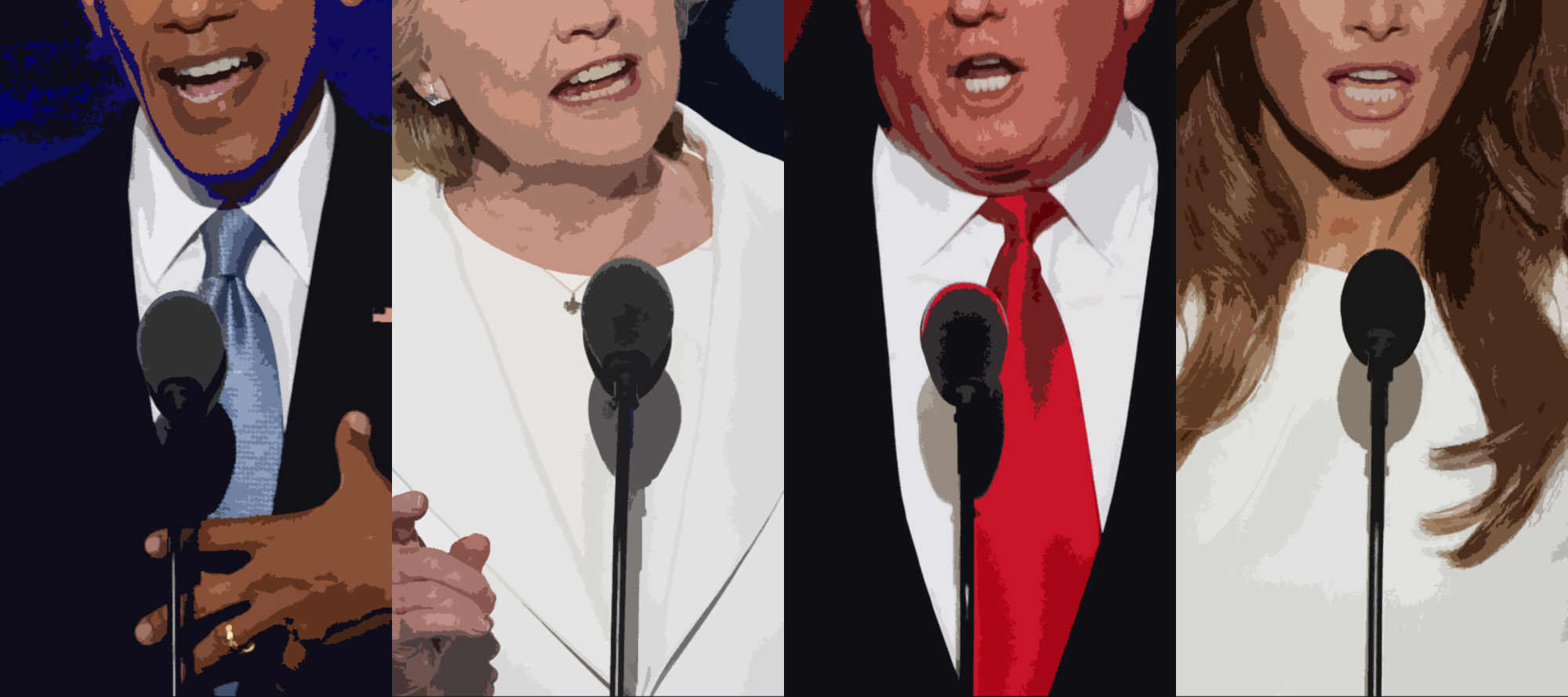

The 2016 race has seen a flood of ghostwriters and speechwriters peeking out from behind the curtain to remind us of their existence — and that these are not your politician's words

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When it comes to electoral drama, we live in debased but discerning times. Few Republican and Democratic conventions have more notoriously revealed our political theater to be just that: stagecraft and scripts. We've consented to this. We demand it, in fact: Critics on either side who feel that Bernie Sanders shouldn't have looked so glum, or that Ted Cruz should have endorsed Donald Trump, are explicitly demanding veneer over substance, and a lot of horse-race coverage frames its questions in terms that interrogate strategy rather than principle: How will Trump appeal to Bernie supporters? What demographic did Clinton hope to court with Katy Perry? Frankly, the expectation of sincerity is so passé that many observers (I include myself) are surprised when a moment that feels authentic takes place at an event that mostly doesn't.

This isn't as cynical as it seems: The people demanding that Sanders and Cruz conceal their true feelings believe — perhaps rightly — that political theater sometimes matters more than political fact. The appearance of unity has power in the same way that smiling can allegedly make you feel happier.

Nor is it necessarily symptomatic of greater corruption; if anything, it may be an unintended psychological consequence of greater transparency. Americans know so much about how these spectacles are produced now — or we think we do, thanks to shows like HBO's Veep and Netflix's House of Cards — that we easily slip into a knowing complicity. Instead of viewing these spectacles as consumers, we start thinking of them from the production side. (This is true of celebrity culture too: Much of the admiration viewers express toward savvy users of platforms like Twitter, Snapchat, reality TV, and Instagram has morphed from consumption to production — from simple admiration for the subject to admiration of the subject's management and manipulation of their own image.)

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But a major reason it feels like we have so much backstage access to the 2016 presidential race is the flood of ghostwriters and speechwriters peeking out from behind the curtain to remind us of their existence and that these are not your politician's words. They seem less discreet than they've ever been, these shadowy figures who write the things we like to pretend our speakers say. (Obama's speechwriter Cody Keenan told Northwestern he believed presidential aides should "be possessed of high competence ... and a passion for anonymity." Now he's showing up on TV.)

And what speechwriters and ghostwriters say matters, because they have access. Real, unfiltered access. That's why Tony Schwartz's decision to talk about his real impressions of Trump while ghostwriting The Art of the Deal for him was so damning: Schwartz listened to the man's phone calls. He saw his tantrums.There's real intimacy there — and its intensity is evident even in Melania Trump's plagiarism scandal (6 percent of her speech at the Republican National Convention was lifted from First Lady Michelle Obama's speech at the Democratic National Convention in 2008).

Once the Trump campaign stopped insisting that what had clearly happened never did, it came out with a different story: Two experienced speechwriters wrote a speech for Melania, but she didn't like it, and turned to longtime ghostwriter Meredith McIver for help.

Whether she's actually responsible for the error, McIver publicly assumed responsibility with a humility that reflects the odd temporary sacrifice of the self that hunts the ghostwriter (or speechwriter) and the subject or cause she serves. This is the compromise: You don't get the credit but you will get the blame. The Melania affair led to a kind of nationwide crash course in speechwriting: what it means, how you're supposed to do it, what's fair, and what isn't. Asked to weigh in, Michael Gerson — former chief speechwriter for George W. Bush — called the plagiarism a "staff failure." Sarah Hurwitz, the woman who actually wrote Michelle Obama's speech in 2008 (and Hillary Clinton's concession speech that same year!), got a profile. Obama speechwriter Jon Favreau speaks often on the experience of working with the president. He even has his own podcast at Bill Simmons' The Ringer. Michael Waldman, a speechwriter for Bill Clinton, talked about how Hillary helped edit her husband's first State of the Union address. (He has also said, elsewhere, that Bill Clinton reached out to lots of people for input from everyone and that George W. Bush "kind of took what was handed to him.")

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It's a big deal for a speechwriter to turn on a cause. It's a particularly big deal for Doug Elmets, a former speechwriter for Ronald Reagan, to call the 2016 Republican nominee a "petulant, dangerously unbalanced reality TV star" at the Democratic National Convention. Or for Mark Salter, former chief of staff and speechwriter for John McCain (and ghostwriter for several of McCain's books) to do the same.

This isn't exactly new: Proxy writers have always been menaces. Andrew O'Hagan's 2014 essay for the London Review of Books on ghostwriting Julian Assange's aborted memoir is well worth reading, and Paul Fenjves' introduction to the book he wrote for O.J. Simpson, If I Did It, is one of the more damning accounts I've read of that famous case. Barton Swain wrote a book on the misery of speechwriting for South Carolina Gov. Mark Sanford before his curious fall from grace.

But the speechwriters might be coming out in record numbers this election season because we need them. They yank us out of that eerie tolerance for fiction that "reality television" trains into its viewers. They force us to question our surrender to spectacle. Depending on their convictions, viewers tended to condemn a particular convention's spectacle for its dystopian aspects (some found Trump's speech and stagecraft fascist) or, on the flip side, to praise it for its entertainment value (others loved his showmanship). Or take the DNC video introducing Hillary Clinton:

It was directed by Shonda Rhimes and narrated by Morgan Freeman. Many of the responses I saw on Twitter were appreciations for the decision to have "God" narrate Clinton's life on what looked like a Nancy Meyers set. The same reflexive celebration of artifice takes place on the other side, perhaps more perniciously: When Trump is caught lying or distorting the truth, his supporters seem convinced that the lie itself is trivial — a bit of trolling meant to enrage their opponents — and that they themselves are in on the joke.

Here's what unites these tendencies: They aren't assessments of content. They're assessments of presentation. They're bad habits formed by the bizarre change in context Donald Trump has managed to exert.

If you have someone insisting he's the author of everything (and so is his wife), the ghostwriters have to come out. It's an intervention worth marking and appreciating. Americans may be slightly savvier consumers than we pretend to be when, for example, we praise someone for "his" or "her" speech at the conventions. What we really mean, in delivering that praise, is that we're impressed with its slot in the lineup. We're very likely impressed with the line-readings, the delivery that helped it work. We're impressed (or horrified) by whatever ideas the speaker articulates.

Now, ideally, we remember that we're assigning these attributes to the speaker only because it's more convenient to do so than to name the vast apparatus that goes into engineering these enormous theatrical arguments. But authorship — thanks to the gigantic claims Donald Trump has made on it — has never been more dead than it is this year. Blame whatever you want: Veep, reality TV, Twitter. But thank the ghostwriters and speechwriters, who are reminding us of the author's constructedness and coming out en masse.

Lili Loofbourow is the culture critic at TheWeek.com. She's also a special correspondent for the Los Angeles Review of Books and an editor for Beyond Criticism, a Bloomsbury Academic series dedicated to formally experimental criticism. Her writing has appeared in a variety of venues including The Guardian, Salon, The New York Times Magazine, The New Republic, and Slate.

-

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’Feature An office doormat is stranded alone with her awful boss and a frazzled therapist turns amateur murder investigator

-

Movies to watch in February

Movies to watch in Februarythe week recommends Time travelers, multiverse hoppers and an Iraqi parable highlight this month’s offerings during the depths of winter

-

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance iceberg

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance icebergIN THE SPOTLIGHT Federal troops are increasingly turning to high-tech tracking tools that push the boundaries of personal privacy

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred