What if Donald Trump is super popular in 4 years?

If the economy keeps improving, he might be

Friday's jobs report was more evidence of the kind of slow, plodding improvement we've grown accustomed to since the end of the Great Recession. But now that Donald Trump is about to become president, what happens if the slow, plodding improvement keeps up? The answer is a nightmare for Democrats: Come 2020, Trump could be very popular.

Political science suggests the economy is enormously important in predicting how an election will swing. In fact, the most stupidly simple models of Americans' voting behavior — the ones that account for the economy, which party is incumbent in the White House, Americans' natural tendency to change course, and little else — predicted the outcome of the 2016 election just fine. In fact, they were saying Trump was the likely victor months ago. It's just no one believed them.

Contrary to some triumphalist assessments you may have read when everyone still thought Hillary Clinton was a shoe-in, the economy is not doing well. Labor force participation and the prime-age employment ratio are still unusually depressed, and under-employment is still unusually high. The rate of wage growth still shows we haven't flipped from workers competing for jobs to employers competing for workers. Costs of health care, housing, education and such are still crazy high compared to past decades, and huge numbers of American households are still financially insecure. Simply put, the economy still kind of sucks.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Now, according to the models, it's the rate at which the economy improves, especially in the year prior to the election, that really matters. That rate did speed up noticeably in 2015. But it wasn't enough to save the Democrats. If things stay as they are, that rate might not help Trump/Pence 2020 much either.

At the same time, it seems weird to assume the overall health of the economy doesn't matter at all. Four years of improvement at this rate will result in a much healthier economy, and one much closer to what Americans have historically associated with prosperity.

All of which certainly isn't a slam dunk case that Trump will waltz back into the White House in 2020. But it certainly seems like a plausible case.

To which you might ask: What about that looming recession I keep hearing about? Well, the biggest reason economists all have their eyes peeled for one is just historical precedent. Recessions in the modern era have tended to hit every 8 to 10 years. So if past is prologue, we're due for one. But there's not really much in the way of concrete evidence that a recession is looming on the horizon.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Since 1980, recessions have been driven by bubbles that pop. The two obvious candidates for a new bubble are student loans and auto loans. But while both problems are doing a lot of damage to Americans' livelihoods, they have nowhere near the scale or market reach of either the 2001 tech bubble or the 2008 housing bubble. Their internal dynamics are also different: They're unlikely to unravel and bring down the whole economy, the way the dotcom bust or the housing crisis did.

You can also look for signs of a recession in the economy's fundamentals: Layoffs are still trending down, which is good; initial jobless claims and the quits rate don't show any warning signs either. The rate of hiring looks sketchy, but it can plateau for years before the economy tanks.

So again, it's not a slam dunk case that we won't see a bubble and recession in the next four years. But the possibility we avoid one is very real.

This means if Trump and the Republicans want to win in 2020, doing absolutely nothing between now and then would actually be a pretty smart strategy. More realistically, if Trump just pulls off some publicity stunts while not doing anything substantive to affect the economy, he might be in a very strong position. Think the recent Carrier deal or even building the Mexican-border wall. (At the same time, we don't actually know how the U.S. populace would react if it actually got a taste of hardcore white nationalist policy in action — but the 2016 election results are not promising.)

The great hope for Democrats, then, is that their opponents will do something about the economy. Because most of what the GOP is talking about doing would be a disaster. Passing House Speaker Paul Ryan's budget would gut government aid and public investment, sucking huge amounts of aggregate demand out of the economy. Trump's tax cuts would allow the rich to claim bigger slices of the wealth generated by businesses, making wage stagnation for everyone else more likely. If Trump and the Senate GOP fill the Federal Reserve's two open seats or replace Fed Chair Janet Yellen with inflation hawks, the Fed might hike interest rates faster, thereby depressing the economy.

Of course, Trump was all over the place in terms of policy during the campaign. So maybe he'll fight Ryan's budget. Maybe he'll work with the Democrats to pass an infrastructure bill that isn't useless corporate giveaways. But presidents tend to dance with the party that brung 'em.

If the Democrats want to win again in 2020, their best hope — and it's a very reasonable hope — is that Trump and the Republicans sabotage themselves.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

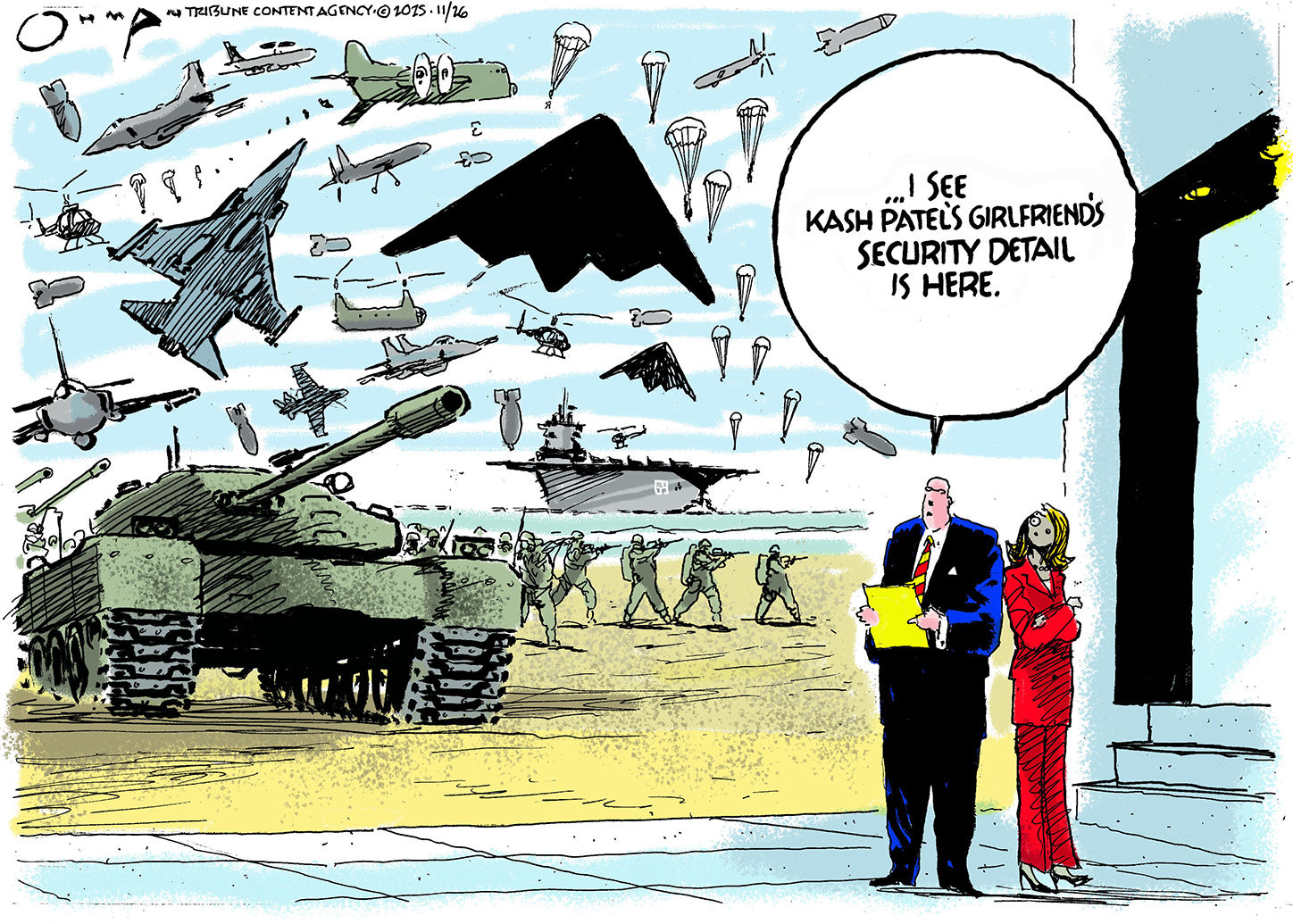

Political cartoons for November 29

Political cartoons for November 29Cartoons Saturday's political cartoons include Kash Patel's travel perks, believing in Congress, and more

-

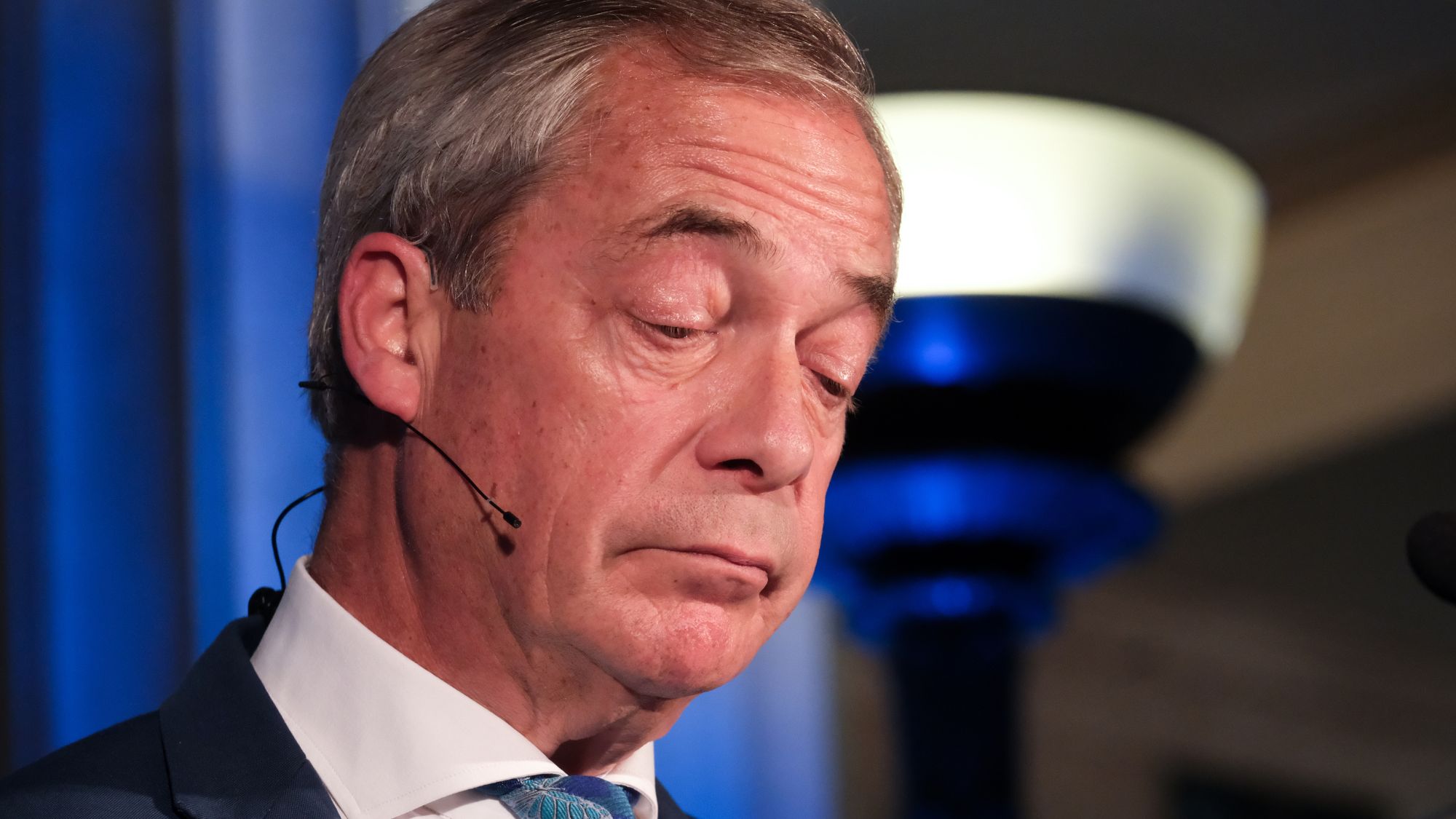

Nigel Farage: was he a teenage racist?

Nigel Farage: was he a teenage racist?Talking Point Farage’s denials have been ‘slippery’, but should claims from Reform leader’s schooldays be on the news agenda?

-

Pushing for peace: is Trump appeasing Moscow?

Pushing for peace: is Trump appeasing Moscow?In Depth European leaders succeeded in bringing themselves in from the cold and softening Moscow’s terms, but Kyiv still faces an unenviable choice

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration