Are we actually headed toward a recession?

The economy is sending lots of mixed signals

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There's a scarily familiar question that's been itching the back of America's skull as of late: Namely, are we about to hit a recession? The data is in and the answer: Maybe?

Let's start with the bad news. One thing that can show you how worrisome things have gotten in the economy is called a "junk bond spread." Bonds, remember, are debt: the financial instruments governments and corporations use to borrow. And while it might sound rather dramatic to call something a "junk bond," it actually just means a bond with an unusually high level of risk. There's a place for them in any economy: Some investment projects are just intrinsically riskier than others, but could still be valuable. And the flip-side of being unusually risky is that the bonds pay out an unusually high yield, which can be attractive to investors depending on their strategy or situation.

Generally speaking, junk bonds get rated BB or lower by the major credit rating agencies. "Investment grade" bonds get rated AAA or BBB; these are the ones that people who are looking to save for the long-term, who want low risk and are thus willing to put up with a low yield, park their money in.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

For a range of reasons, government bonds are generally considered the best of the best for "investment grade" bonds. So it's companies and businesses gambling in the private sector that provide the junk bonds. And that means that junk bonds can provide a useful signal. If you look at the "spread" between the yields on junk bonds and the yields on government bonds — i.e. the difference in yields between the safest and riskiest bets in the economy — you can get a rough sense of the overall level of risk in the economy.

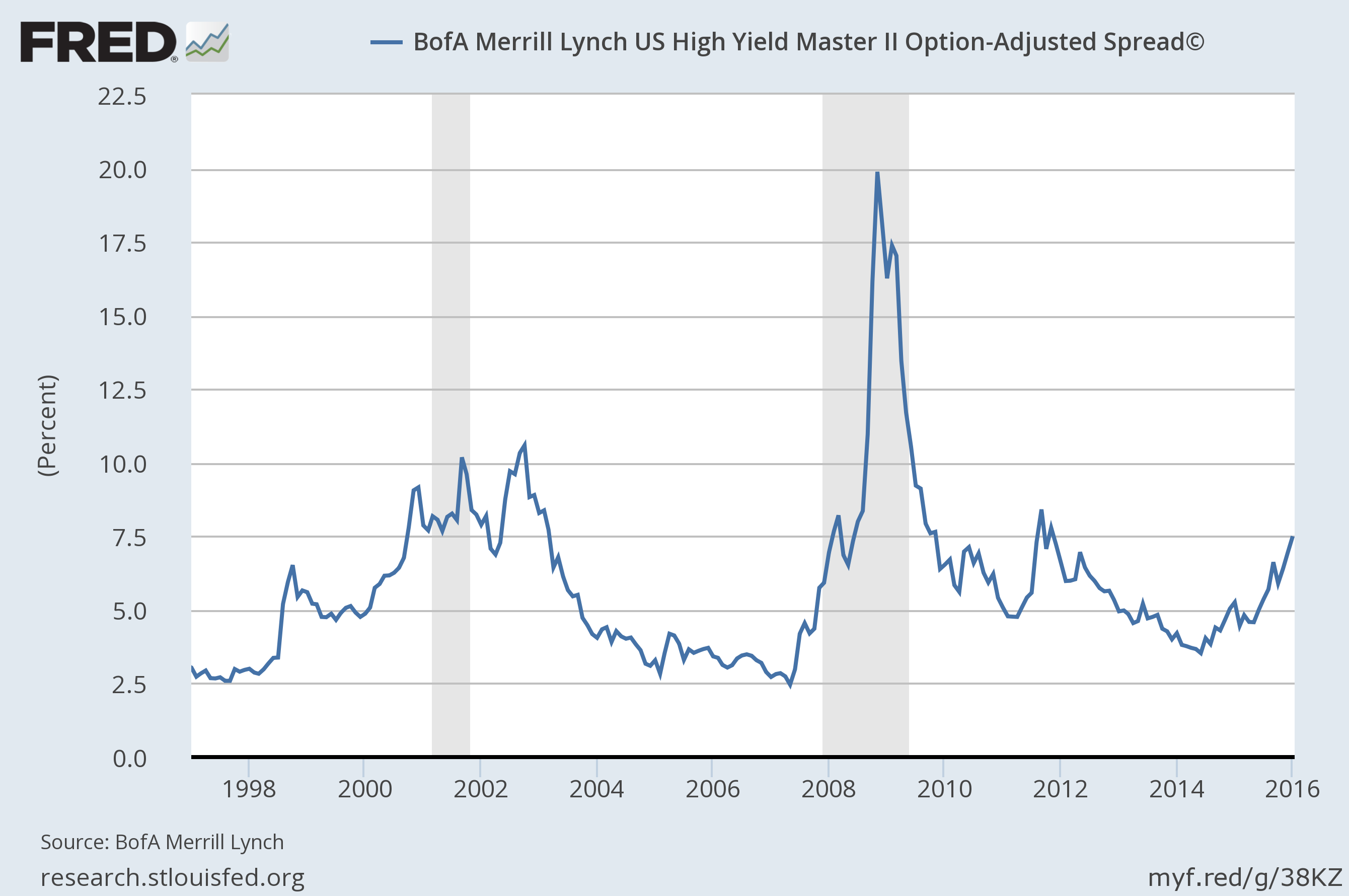

There are lots of different packages of junk bonds you can look at. But recently the spreads have been increasing as the yields on various junk bond packages have gone up, suggesting more individual parts of the economy are becoming riskier. Here's one spread put together by Bank of America and Merrill Lynch that's indicative of the trend:

That spread looks at junk bonds rated BB or below, but another that looks at everything below CCC is doing the same thing. The spreads have typically gone into a decisive uptick in the year and a half or so before a recession, and that's been happening again.

It's not a slam dunk metric; you're talking about a very broad indicator pushed around by lots of forces in the economy. For instance, there's been a huge collapse in oil prices, which drove up the riskiness for bonds related to the oil industry. So that's a big part of the story in what the spreads are doing. But a drop in oil prices isn't an indication of overall weakness in the economy. It's just a really big supply shock in the oil market specifically.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

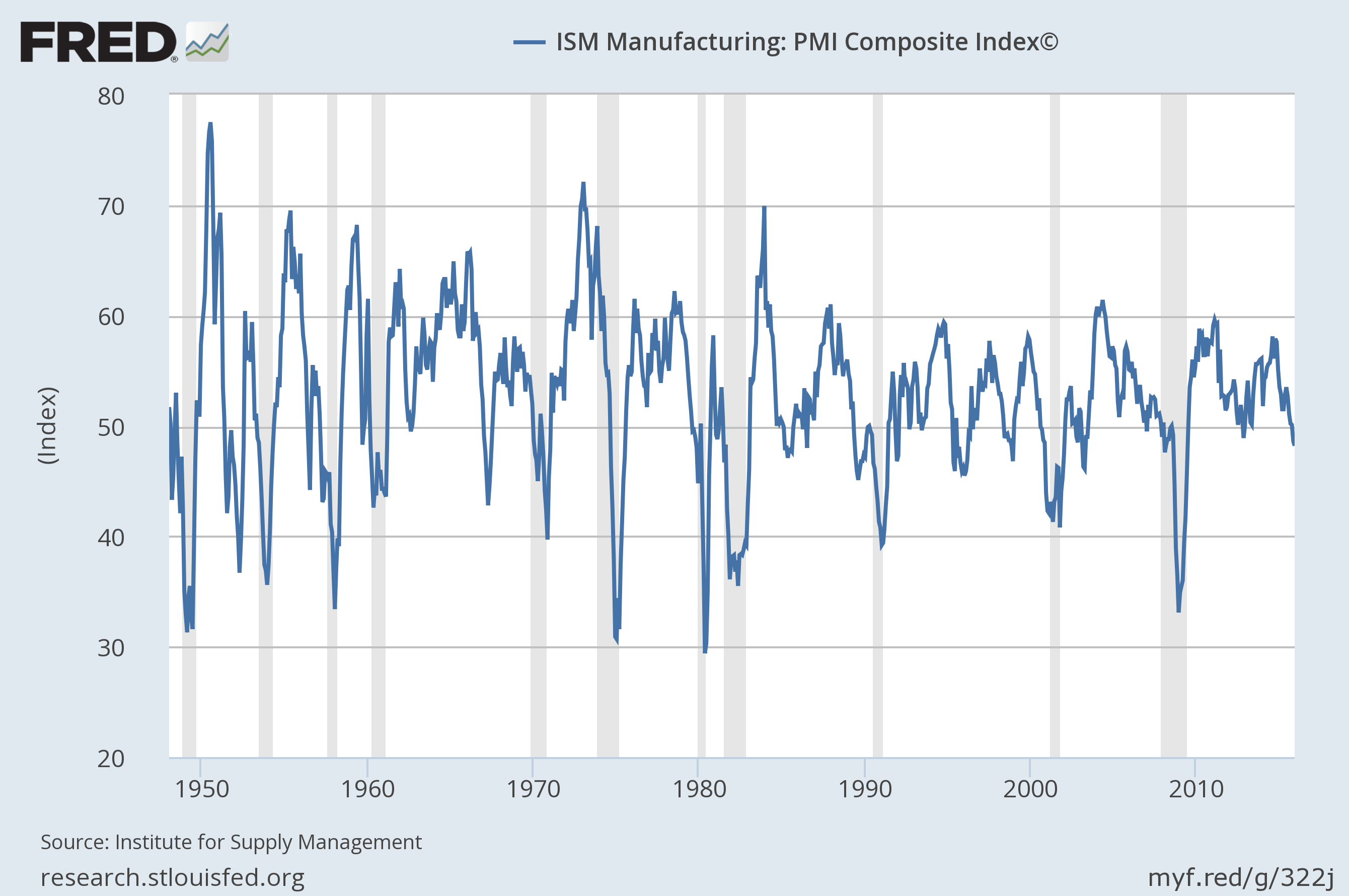

Furthermore, if you look at the graph above, just prior to a recession isn't the only time the spreads have temporarily increased. Another indicator, the ISM manufacturing index, suffers from the same problem. By the index's measure, the manufacturing sector started contracting around the end of 2015, which it tends to do just before a recession. But if you look at the whole history of the index, recessions aren't the only time it contracts (i.e. dips below a reading of 50).

There's also the question of data points. Economics is, in many ways, still a developing field. A lot of the trends we look at are ones we actually haven't been gathering numbers on for that long. You can look at the pattern for mergers and acquisitions, for example, and it sure looks like a recession is coming within a year or two. But then the numbers only go back about two decades. Who knows how long these trends stick with particular predictable forms of behavior?

Ultimately, many clues indicate we could be heading for a recession. But they're all circumstantial.

Tim Duy, an economist at the University of Oregon, noted on his blog that, "It's not a recession until you see it economy wide in the labor markets. When it's there, you will see it everywhere." How many jobs there are and how well they pay is really the foundational question when it comes to an economy's health. Unfortunately, as Duy acknowledged, this doesn't help us much. Employment is also a lagging indicator, so by the time you see the drop in overall employment, the recession's already here.

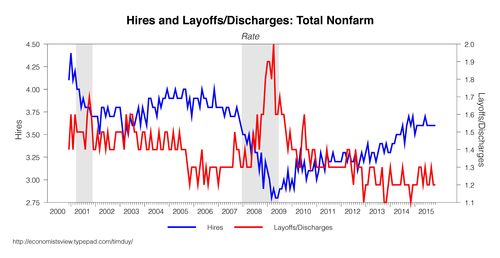

But if you look under the hood at some indicators related to employment, you can find trends that tend to do some distinct things ahead of recessions. Duy mentioned several, but three that really stand out are the rate of hires versus layoffs and discharges in the economy, the rate of quits in the economy, and initial jobless claims. Here they are:

As you can see, the rate of hires and the rate of layoffs and discharges tend to converge — the former slowing down and the latter speeding up — in the runup to a recession. As of the end of 2015, they weren't doing that yet.

(Graph courtesy of Tim Duy.)

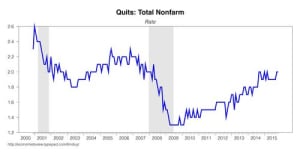

Similarly, the rate of quits slows down before a recession. In a booming economy there are lots of job opportunities, so people have more confidence that if they quit a job they're not happy with they can find something better. Conversely, when the economy is headed for a slowdown, things look worse, so people quit less often. As of the end of 2015, there was no real slowdown in the quits rate.

(Graph courtesy of Tim Duy.)

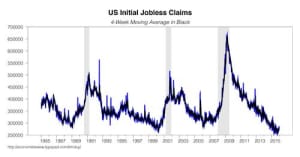

And finally jobless claims, which are how people file for unemployment benefits, tend to jump upwards before a recession for obvious reasons, but that doesn't seem to be happening yet either.

"I am not seeing conclusive evidence of an impending recession in manufacturing, let alone the overall economy," Duy concluded, though he allowed "there are perfectly good reasons to be wary that a recession will bear down on the economy in the not-so-distant future." Other economists like Paul Krugman and Dean Baker don't think a recession is imminent either, though Baker thinks we're likely in for slower growth in 2016.

The big worry is China and the global economic slowdown. But China's financial linkages to us are far stronger than our linkages to them. And while America exports more in a globalized world than it did a few decades ago, the sizeable majority of the demand that drives our economy is still provided internally. It would just take an enormous crash on China's part to hurt us much.

That said, the Fed did finally begin tightening recently, and Duy admitted in his blog post that usually means the clock is ticking: "By that time, the economy is typically in a late-mid to late-stage expansion, and you are looking at two to three years before the cycle turns, four at the outside."

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.