Why the Great Merger Frenzy of 2015 signals another recession

You get a spike in deal-making, and then a year to a year-and-a-half later, you get the recession

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When is the potential merger of two centuries-old chemical industry behemoths not the biggest story in economics news?

The answer: When it's merely the capstone to one of the biggest frenzies of corporate mergers in years.

Dow Chemical and DuPont — established in 1897 and 1802, respectively, and with a market value of about $60 billion each — are in talks to combine forces. The proposal may yet come undone, but if it goes through, it would just add to 2015's flurry of mergers: Think Pfizer and Allergan for $160 billion (the second-biggest health care deal on record), Dell and EMC Corp. for $67 billion (the biggest tech deal on record), and Anheuser-Busch InBev and SABMiller for $108 billion (the biggest beer deal on record).

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

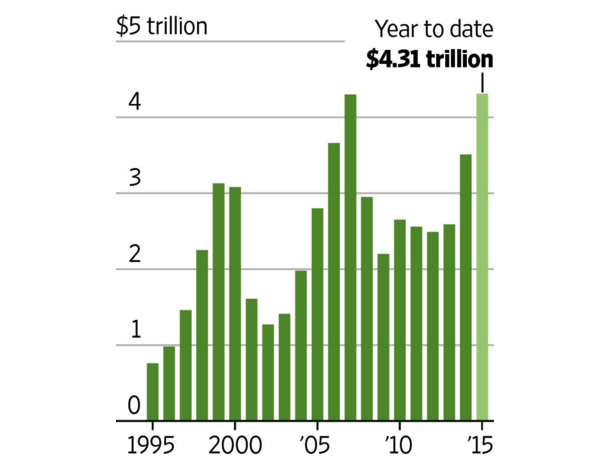

In fact, when U.S. coffee maker Keurig Green Mountain got bought out for $13.9 billion earlier this month, 2015 hit the all-time record: 18,603 deals completed for a total value of $4.614 trillion. The previous peak was 2007, which had a higher number of deals at 23,577, but topped out the total value at $4.610 trillion. Before that the highest peak was 2006, and before that it was 1999, and then 2000.

Hopefully, observant readers are now arching their eyebrows.

We saw a run-up through the late 1990s that collapsed in 2001, then another run-up that collapsed in 2008. Each spike in merger deals has been reliably followed by a recession the next year. And here we are, seven years after the Great Recession, rapidly heading for new heights. Here's a chart of the dollar value of mergers and acquisitions announced globally, by year.

(Courtesy of the Wall Street Journal, data from Dealogic.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Those are the global numbers, but America has been home to the considerable bulk of the deals, hitting $1.47 trillion back in August. The runner-up was China, at $350 billion.

So is this yet another sign that the United States is barreling toward a recession?

The conventional wisdom is that a rising tide of mergers and acquisitions signals business confidence in the economy. But earlier this year, Andrew Ross Sorkin laid out at The New York Times how, in line with a pattern of pre-recession spikes, mergers and acquisitions flurries could also signal the opposite.

Lots of the big players in the recent mergers — Dell, EMC Corp., Anheuser-Busch and SABMiller — have seen revenue collapse by tens of billions of dollars, and profits turn to losses in the hundreds of millions. The fundamental, organic engine for any company to see revenue and profits rise is vibrancy in overall economic activity. You need lots of customers with the means and the motive to buy goods and services, which all adds up to robust aggregate demand. So in the absence of that bottom-up force, according to a Citigroup study that Sorkin cited, companies can turn to mergers and asset restructuring to cut costs through new economies of scale, rejigger financial flows, and thus get their financial books back in the black.

Big companies that have been cutting their way to profitability for the last several years have run out of costs to cut. So what do they do? Merge to cut costs even more."Corporate consolidation can perhaps provide some last drops of stock market intoxication," Spiros Malandrakis, an analyst at Euromonitor, wrote last month about the potential beer merger. [Andrew Ross Sorkin, The New York Times]

One added wrinkle in DuPont and Dow's case is the talk that, following the merger, the new company may split three ways: a business for agricultural chemicals, specialty products, and materials like plastics. That's not necessarily surprising, since a slowing economy can put different pressures on different sectors depending on what other forces are in the mix. The companies have faced weak demand for agricultural chemicals, but the natural gas boom has saved their plastics division through lower energy costs. There's also the question of how rising inequality layers atop the economic slowdown, since it means some pockets of the economy — namely, the ones that both serve and employ the upper class — are doing fine.

At any rate, all this activity temporarily maintains companies' profits, keeping them attractive to investors. But it's not profit or revenue that's grounded in any foundation. So as the bottom-up force of the economic vibrancy keeps waning, the mergers become more and more frenzied to stay ahead of the inevitable, and to keep squeezing a little more blood from the stone. Then the economy goes into a downturn and the bottom falls out of the merger boom.

Crucially, this makes mergers a symptom, not a cause, of recessions. But it also makes them an early symptom: You get a spike in deal-making, and then a year to a year-and-a-half later, you get the recession.

It might be a big recession, or it might be a small one. The 2008 collapse was much worse than the 2001 bust. The total number of mergers in 2007 was higher than in 2015, which could've signaled a broader level of desperation throughout the business world. And a lot of the big buyouts this time around have been undertaken by companies already flush with extra cash holdings, so the deal-making hasn't relied on debt financing to the same degree as in 2007.

It all depends on the deeper forces driving the recession, and how far they reach into the fundamentals of the economy. Which also implicates macroeconomic efforts by the government, like monetary policy and fiscal stimulus.

Eyeballing the previous patterns, we may well have at least another year for the buyouts to rise to all-new frenzied heights before the fall-off hits. But you can add it all to the growing list of evidence that the U.S. economy is about to fall on its face again.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day