20th Century Women, and the movie as mixtape

How Mike Mills' new coming-of-age story challenges narrative convention

Can you write a portrait of the artist as a young man by writing the women around him? That's Mike Mills' question in 20th Century Women. The film, which hit theaters on Christmas, manages to be both a bildungsroman — that single-minded story of the artist's spiritual formation — and its opposite, an ambitious and intertextual ensemble work so promiscuous in its sympathies that there's barely room for a plot. A coming-of-age story for a teenage boy named Jamie Fields (Lucas Jade Zumann), the film is also — maybe even principally — an almost encyclopedic portrait of how two and a half generations of women lived in 1979.

If those seem like competing narrative impulses, they shouldn't. It ought to be possible, given our long experience as discerning observers of screens, to take in a complete story, a story that doesn't capitulate to a zero-sum logic of narrative subordination that holds that, for some characters to be round and retain our emotional investment, others must become flat.

Still, the convention of the spotlight exists for a reason: Complete stories are messy and aimless. In this sense, they swing a little too close to history. We're used to dealing with one protagonist at a time, and there can be an irritatingly untethered quality to a story that takes on several. It makes it hard to meaningfully empathize in any particular direction (this is an area where the TV series, with its broader canvas, has consistently outperformed film — see Transparent, Getting On, Orange is the New Black, etc.). And writing those empathetic cross-currents concisely without descending into unearned feel-goodery or utopianism — honoring the inevitable conflicts, in other words — is harder still. 20th Century Women rises to that challenge and it almost pulls it off.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Almost, but not quite.

The most widespread criticism of this film is that it lacks a plot. The critique has merit — there is no real arc in this film — but this is more a genre problem than a narrative one. 20th Century Women is really more mixtape than movie. It's a funny and idiosyncratic amalgam of scenes in lieu of songs, a collection whose charm derives more from messy, seductive juxtapositions than from anything as coherently ordered as an album. For that to coalesce into a plot in the sense these critics mean, someone's story would have to achieve centrality. No one's ever does. (To take one example: When one character snaps a photo of another, saying she's photographing everything that happened to her that day, the other says, "I don't like having my picture taken. I didn't happen to you." Rarely has the arrogance of protagonism been so explicitly called out.)

The film opens with a Ford Galaxie on fire in the parking lot of a grocery store. Dorothea Fields, played by Annette Bening, watches the family car — the one she brought newborn Jamie home from the hospital in — burn. Bummed but gracious (Bening does this affect so well), she invites the firefighters to a party to thank them. It's a peculiar invitation, as Jamie points out, made even stranger when we learn that it's Dorothea's birthday. (Is she trying to date, perhaps? No, nothing so predictable.) Jamie brings out the birthday cake Dorothea baked, she acts surprised, and everyone — including the firemen, who inexplicably came — sings. It's a lovely introductory vignette of a woman we'll come to know well: dismayed, intelligent, open, tough, and a great believer in the healing power of parties. An odd duck.

It's no coincidence that Dorothea shares a last name with Hal Fields, the gay father played by Christopher Plummer in another of Mike Mills' films, Beginners. Mills wrote the latter about his father as he was dying, and 20th Century Women is largely based on the women in his early life: his mother, his sister (who inspired the character Abbie, a 24-year-old photographer with cervical cancer played by Greta Gerwig), and several of his friends, many of whose stories he mined to write Julie, Jamie's 27-year-old friend (played by Elle Fanning). If Mills were a more conventional filmmaker, this movie would follow his stand-in Jamie's struggle to understand How to Be A Man by toggling between the "real world" (this would include his guy friends, one of whom beats him up for talking about clitoral stimulation) and these women.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Typically, this kind of man-in-training story requires jettisoning the girls and their enervating influence. There'd be a poignant scene about the agony of masculine self-fashioning. We'd see the artist abandon womanish things in order to define himself and his quest. To its credit, 20th Century Women refuses that clichéd and artificial frame: Jamie is clear on where his loyalties lie, and so is Mills. The lens follows the women. At no point does it deny or downplay their influence. They are not obstacles to be outgrown. (This may not seem all that revolutionary until you try to make a list of movies about sons and mothers that doesn't pathologize the relationship.)

Here is the plot, such as it is: Dorothea is worried about her son, whose father is no longer in the picture. She invites men to the house — a wonderful half-ruin she's trying to restore with scaffolding up the side — not for herself but for him. Her hope is that Jamie will bond with and learn from them what he can't learn from her. Jamie, unfortunately, has nothing to say to their lodger, William (Billy Crudup), a weak but well-meaning handyman who fixes cars and helps Dorothea with house projects. Instead, he spends his time with Julie, an unsmiling 17-year-old who routinely sneaks into his room to sleep chastely next to him and "do therapy" in imitation of her mother, and Abbie, a Bowie-loving cancer patient whose mother turned mean with guilt after learning that her daughter's cervical cancer was caused by a drug she took while pregnant.

When Jamie plays an asphyxiation game with some other boys and winds up hospitalized, Dorothea enlists Abbie and Julie's help in raising him, entrusting them with his education and well-being in domains that she herself can't reach.

There is no deputizing teenagers and 20-somethings as co-parents without side effects, and Jamie resents the arrangement almost as much as they do. Still, 24-year-old Abbie shows Jamie The Raincoats. She gives him Sisterhood is Powerful and Our Bodies, Ourselves, and takes Jamie along to her cervical cancer appointment, where he reads magazines about pregnancy tests and buys one for Julie, who talks to him about the sex she's having with other boys and recently informed him that one didn't pull out.

This is not quite what Dorothea had in mind.

It becomes clear that Jamie feels wounded by what he sees as his mother's decision to delegate his upbringing to his friends. If Dorothea tries to understand her distant son through music — one of the film's best scenes has Bening and Crudup listening to Black Flag and the Talking Heads, trying to understand — Jamie tries to understand his mother through feminism. In a particularly heartbreaking scene he reads her a passage from Zoe Moss' "It hurts to be alive and obsolete: The ageing woman." Dorothea understands what he's thinking immediately and shuts him down. She tells him, gently but firmly, that he thinks that's her, but she does not need a book to know about herself.

Films set in specific historical periods tend to get a little fetishistic about historical markers; what's wonderful about 20th Century Women is that the Moss essay isn't there just for color; it appears in the service of a particular dramatic moment. As hard as it is to watch Bening's Dorothea swat down Jamie's effort to connect through Zoe Moss, you can kind of see her point: She doesn't quite fit the description, and it's insulting to be slotted into it by her son. Despite her openness, Dorothea turns out not to be especially receptive to feminist thought. In fact, she tries to rescind the parental authority she gave Abbie, asking her to stop giving Jamie "hard-core feminism."

Abbie refuses, and this is the richest conflict in the film. Unfortunately, Mills doesn't nail the conflict or the landing. The friction between Abbie and Dorothea is much too intense for it to dissipate the way it does. It should have yielded an actual crisis, maybe even a breakage. Mills is a little reluctant to pull the trigger on dramatic scenes, and this is one place where a little plot would have gone a long way.

But there is a plot if you zoom out just a little farther than the camera invites you to. 20th Century Women is about a period of distance between a mother and a son, and it spends a lot of time on footage of Dorothea thinking: in the tub, in her bedroom, smoking. She's always trying to solve a problem, always ruminating, always trying to keep track, to understand, to learn. Sometimes she can't. Sometimes she won't. But she tries. Perhaps the real story — the missing resolution in a film that announces its ending without quite earning it — is that Jamie does all this too. The film itself is a record of Mills' Dorothean ruminations, his Fieldsian effort to learn and describe and understand the person to whom he was once closest.

Lili Loofbourow is the culture critic at TheWeek.com. She's also a special correspondent for the Los Angeles Review of Books and an editor for Beyond Criticism, a Bloomsbury Academic series dedicated to formally experimental criticism. Her writing has appeared in a variety of venues including The Guardian, Salon, The New York Times Magazine, The New Republic, and Slate.

-

'America's universities desperately need a reset'

'America's universities desperately need a reset'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

8 hotels that show off the many facets of Japan

8 hotels that show off the many facets of JapanThe Week Recommends Choose your own modern or traditional adventure

-

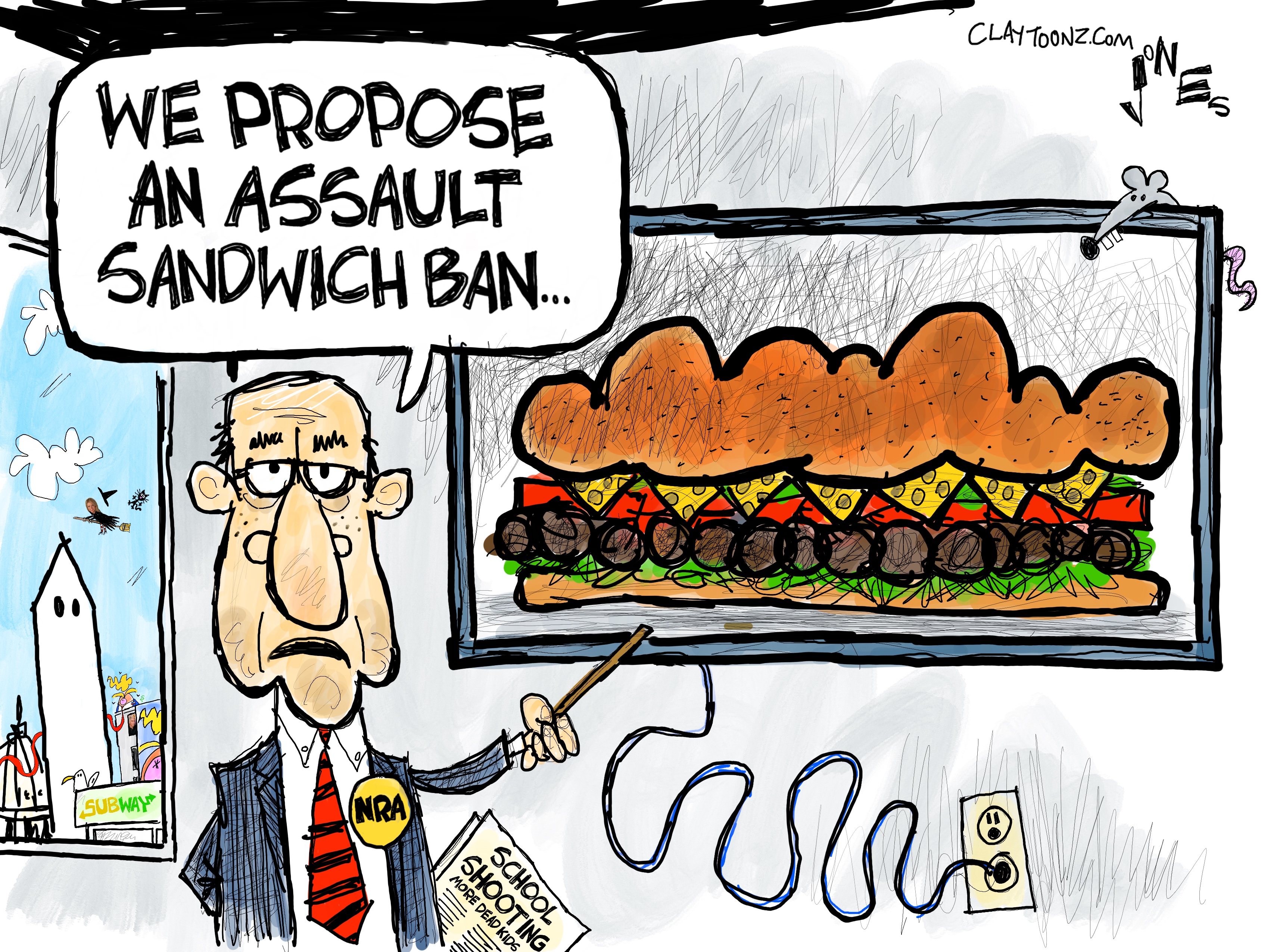

10 Editorial cartoons for August 29

10 Editorial cartoons for August 29Cartoons Friday’s political cartoons include a modest NRA proposal, Smithsonian revised, and the difference between Donald Trump and Abraham Lincoln's hats

-

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'The latest biography on the elusive tech mogul is causing a stir among critics

-

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!The Explainer Please allow us to reintroduce ourselves

-

The Oscars finale was a heartless disaster

The Oscars finale was a heartless disasterThe Explainer A calculated attempt at emotional manipulation goes very wrong

-

Most awkward awards show ever?

Most awkward awards show ever?The Explainer The best, worst, and most shocking moments from a chaotic Golden Globes

-

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. deal

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. dealThe Explainer Could what's terrible for theaters be good for creators?

-

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'The Explainer Move over, Sam Elliott and Morgan Freeman

-

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020feature So long, Oscar. Hello, Booker.

-

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortality

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortalityThe Explainer This film isn't about the pandemic. But it can help viewers confront their fears about death.