La La Land's clunky dancing

We are not the dancers we once were in America, and maybe that's okay

For all their crazy chemistry, the stars of Hollywood's new musical, La La Land, don't actually sing or dance all that well. Somewhat surprisingly, this actually makes the movie work.

Musicals are famously one of the most challenging art forms, not just because of their built-in artificiality, but because they require that a dramatist, choreographer, composer, and lyricist collaborate, and that every singer also be a decent actor and dancer. Yet for a movie in dialogue not just with movies but with musicals specifically, La La Land is an intentionally, even aggressively imperfect film.

Despite winks to Singin' in the Rain — one subplot of which includes dubbing one person's voice with another — La La Land Director Damien Chazelle (formerly of Whiplash) didn't even dub over the leads' wobbling voices. Gosling's piano playing is actually pretty convincing (he learned for the film), but even after two or three months rehearsing Mandy Moore's great choreography, his and Stone's tap routines have a charm that's more amateurish than masterful.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Here's Ryan and Emma:

Here, by way of contrast, are Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers:

As for Gosling and Stone's singing, it's... okay?

Stone told Vogue that it took two nights during the magic hour in Griffith Park to nail the six-minute dance sequence for "A Lovely Night." Still, that's just a few hours. By contrast, Debbie Reynolds' feet famously bled while filming the "Good Morning" song in Singin' in the Rain over a period of 15 hours, and Gene Kelly allegedly had a fever of 103 while performing the title song. Those lovely, easy musicals were extremely hard to make. So are contemporary films about obsessive performers, like Black Swan and, yes, Whiplash (Miles Teller's hands bled from drumming, too).

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Meanwhile, La La Land feels a tiny bit fragile as you're watching it. You see the performers' strain. If this means, paradoxically, that they actually weren't worked to death to eliminate the appearance of effort, it also means that Chazelle's homage to his Hollywood ancestors, while shot in the equivalent of Cinemascope, is experimentally inexact. It's a freckly, unshaven close-up of an entire tradition that built glamor out of perfect skin and perfect timing.

That's noteworthy, because Whiplash, about a drummer's punishing efforts to become a truly great artist, is specifically about obsession and perfection. It's about art with a capital A and the lengths human beings are willing to go to achieve greatness in their chosen field. The extent to which La La Land is not about this startles; it's tantamount to Wes Anderson making a film about functional and happily independent fathers and sons.

In keeping with the dreamy frivolity implied by the title, La La Land's protagonists are fantasists first, artists second. Mia, played by Stone, wants to succeed as an actress, but the role is secondary to the success (she'd be delighted to be cast in a mediocre police procedural, for example). Gosling's Sebastian wants to open a jazz club, but his love of jazz is incurably and even inappropriately nostalgic: Jazz was a cutting-edge, vibrant, experimental form. If Seb was really the purist he fancies himself, he'd find a way to restore it to vitality, to make it new. (This is a point made by Keith, played by John Legend: "How are you going to be a revolutionary if you're such a traditionalist?") But he doesn't: His investment in jazz is at least as much about the wardrobe, the paraphernalia that clutters his apartment. Even though he hates that it's become elevator music, Seb is as much in love with jazz's ambiance as he is with the music itself.

As Mia and Seb's romance develops into a mutual support society for their dreams, it becomes clear that the typical musical's love formulas don't actually translate well to a movie about show business. And despite La La Land's wild nostalgia, the film reveals showbiz in all its cruel and arbitrary grandeur. Musicians are forced to play Christmas jingles. Actors are discovered at horrible parties — or worse, they're ignored. The solution to all this is not pure art, and it certainly isn't love. No: In La La Land, the solution is to try and wait and see. In L.A., the love story is ironically the unromantic, pragmatic bit. It's the career that's dreamy.

It's tempting to try to read Chazelle's own aspirations through this complicated lens. A drummer himself, Chazelle had a personal connection to some of the material in Whiplash. He certainly experienced Mia and Seb's desperate relation to Hollywood, and he's spoken often of his love for the musical — an art form plenty of people consider to be as dead and obsolete as jazz. Is he himself, then, a Seb? A bellicose nostalgic providing a forum, however small, for those who miss the old greats? Or is he a revolutionary trying to revitalize the form?

The latter, I think. The mismatches between expectation and reality in La La Land are crucial to this redefinition of the musical as something that can thrill us in 2016. Stone is much too funny and wry a screen presence to fit the models of stardom to which Mia herself aspires, but that a Stone is in no way a Bergman does not make her any less a star. Gosling will never summon anything resembling Bogart's screen presence; it is still a joy to watch him sulkily play "I Ran." The film rhymes the past with the present carefully, and it knows when to give the parallels up. We are not the dancers we once were in America, and maybe that's okay.

The most fascinating difference between Chazelle and Seb is that La La Land, not Whiplash, was Chazelle's passion project. He wanted "to take the old musical but ground it in real life where things don't always exactly work out." It took him years to find a production and distribution company, and even after he did — Focus Features took it on — he walked away when they tried to modify it too much. (They wanted to gut the ending and to make Seb a rock star instead of a jazz pianist.) So he wrote Whiplash, knowing it would be much easier to sell.

In other words, the film about the obsessive, sensitive artist was Chazelle's sellout, his compromise. The one about the careerist, slightly shallow lovers — who all too happily walked out of Rebel Without a Cause when the projector malfunctioned — was the real dream. You don't make John Legend learn to play guitar for your movie if what you want is perfection. No, you're specifically interested in something else, the spontaneous energy immensely talented people give off when they're working outside their comfort zone and just barely pulling it off.

That, I think, is what makes La La Land work. Show business is about entertainment. It's about fun. It's good to be reminded of that, and even — given the weaponized nostalgia at the end — to wallow both in how imperfectly it all turned out, and in how perfect it all could have been.

Lili Loofbourow is the culture critic at TheWeek.com. She's also a special correspondent for the Los Angeles Review of Books and an editor for Beyond Criticism, a Bloomsbury Academic series dedicated to formally experimental criticism. Her writing has appeared in a variety of venues including The Guardian, Salon, The New York Times Magazine, The New Republic, and Slate.

-

The best dark romance books to gingerly embrace right now

The best dark romance books to gingerly embrace right nowThe Week Recommends Steamy romances with a dark twist are gaining popularity with readers

-

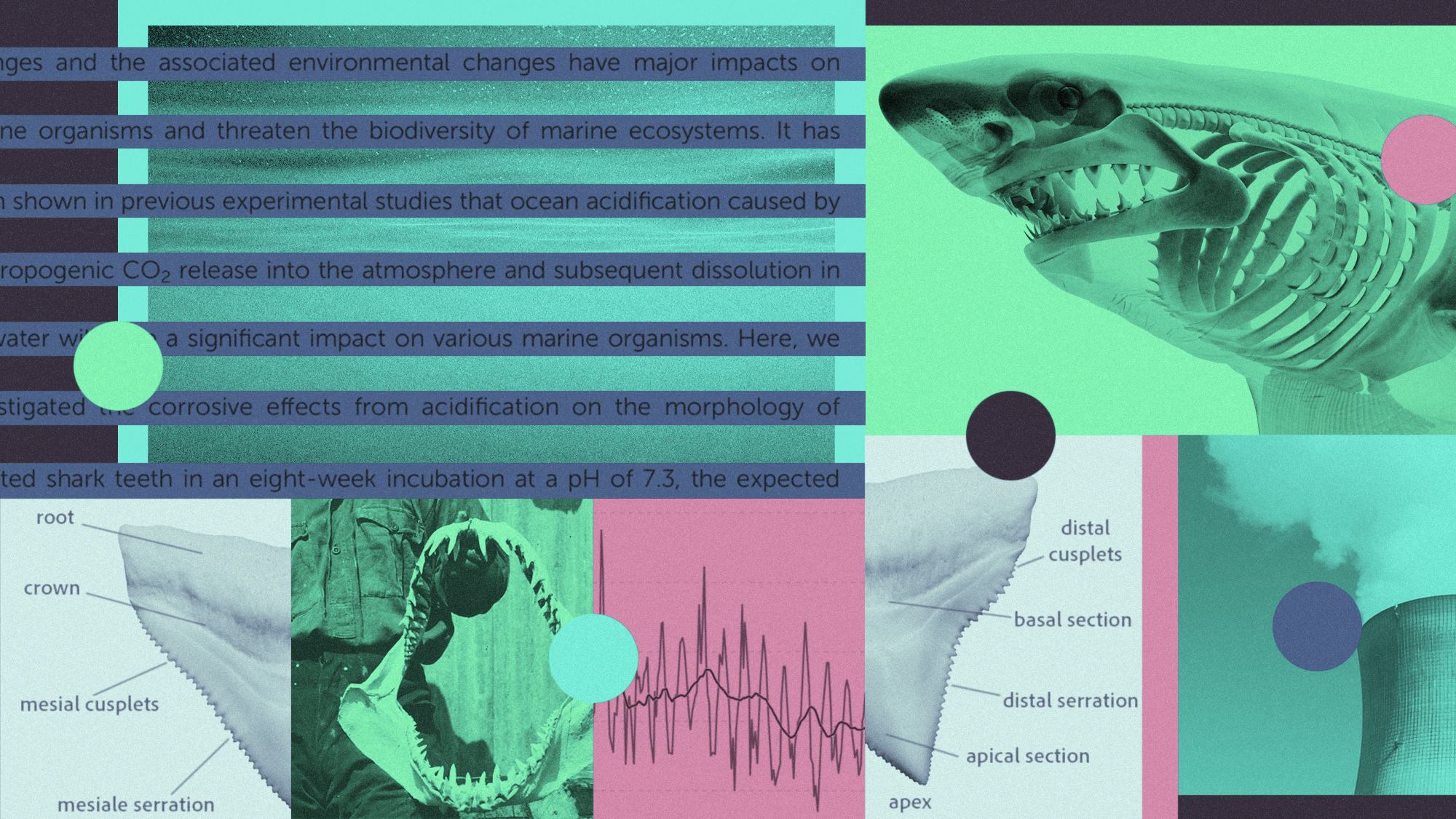

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teeth

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teethUnder the Radar ‘There is a corrosion effect on sharks’ teeth,’ a study’s author said

-

6 exquisite homes for skiers

6 exquisite homes for skiersFeature Featuring a Scandinavian-style retreat in Southern California and a Utah abode with a designated ski room

-

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'The latest biography on the elusive tech mogul is causing a stir among critics

-

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!The Explainer Please allow us to reintroduce ourselves

-

The Oscars finale was a heartless disaster

The Oscars finale was a heartless disasterThe Explainer A calculated attempt at emotional manipulation goes very wrong

-

Most awkward awards show ever?

Most awkward awards show ever?The Explainer The best, worst, and most shocking moments from a chaotic Golden Globes

-

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. deal

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. dealThe Explainer Could what's terrible for theaters be good for creators?

-

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'The Explainer Move over, Sam Elliott and Morgan Freeman

-

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020feature So long, Oscar. Hello, Booker.

-

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortality

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortalityThe Explainer This film isn't about the pandemic. But it can help viewers confront their fears about death.