Democrats are in denial on immigration

Liberals can't just call Trump's immigration policy racist. They need a plan of their own.

There are plenty of good reasons to oppose President Trump's proposed crackdown on immigrants and refugees.

For one thing, there's little evidence that migrants from the Middle Eastern countries the administration would like to ban pose an elevated risk to the United States. For another, "illegal immigration to the U.S. ended a decade ago," according to economist Noah Smith (relying on data from the Pew Research Center), and it "has been zero or negative since its peak in 2007." Then there's the fact that rounding up and deporting the estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants who continue to live in the country would require police-state tactics that may well be more pernicious than allowing those people to stay.

These are pragmatic arguments, and the evidence speaks against Trump's proposals. But what if the pragmatic calculus changed?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What if the U.S. began to suffer deadly attacks perpetrated by terrorists who originated from Muslim-majority countries? What if the number of unauthorized immigrants in the country started to rise sharply (as it did over the two decades prior to 2007)? Or what if a plurality of Americans wanted to drastically curtail rates of legal immigration, or restrict who gets in on the basis of national origin or skill-level?

Judging from the sweeping moral arguments being marshaled against the Trump administration, many left-leaning critics of the president would oppose policy adjustments in such circumstances as well.

Many liberals argue that refugees are among the most vulnerable people on Earth and so must be welcomed with open arms. That forcing undocumented immigrants to leave the country is gratuitously cruel, violates their rights, and so justifies municipalities flouting federal law by turning themselves into "sanctuary cities." That banning entry to refugees or immigrants not yet within the United States can violate their due process rights under the U.S. Constitution. And that the desire to restrict immigration is invariably an expression of xenophobia, racism, and other forms of irrational animus and so morally (and perhaps constitutionally) indefensible.

All of these claims are, at bottom, expressions of a fundamentally anti-political humanitarian ideology that is unlikely to fare well in the next presidential election. Democrats desperately need to confront the vulnerabilities of this position and stake out a more defensible and pragmatic one if they hope to push back against Trump's populist-nationalist message in upcoming years.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Many Americans believe that their constitution presumes or appeals to certain timeless, universal moral truths that apply to all human beings. But the U.S. Constitution itself — like the constitutions, fundamental laws, and commonly affirmed norms and rules of all political communities — is nonetheless instantiated in a particular place, rooted in a particular tradition. It also pertains and applies only to people who are members of the political community known as the United States of America.

Those who are members of this community are known as American citizens. They get a say in what laws get passed and how they get enforced. Those who are not members of this community — who are not citizens — don't get such a say. The community is perfectly within its rights to decide which and how many of these outsiders will be allowed to visit the country, how long they will be allowed to stay, when they will need to go, and how many, if any, will be permitted to join the community permanently by becoming citizens.

This is one of the most elemental acts of politics: the community deciding who to admit and on what terms. To treat this act as somehow morally illegitimate is to treat politics as such as morally illegitimate.

Note that nothing I've said tells us anything about how many immigrants or refugees the political community of the United States should welcome at any given moment of history, or what criteria should be used to make this determination. I generally favor liberal immigration policies; many Trump voters take a very different view. The point, as Josh Barro recently argued in an important column, is that the policy debate needs to be made in terms of the good of the political community as a whole and in its parts, not in terms of abstract, extra-political moral duties owed to prospective newcomers. A political community exists in large part to benefit itself — to advance the common good of its citizens. There's nothing shameful in that. It's to a considerable extent what politics is.

All of Trump's claims about immigration are made in terms of the good of the country as a whole or in part: Immigrants from the Muslim Middle East threaten the U.S. with terrorism; undocumented Latin American immigrants commit crimes, steal American jobs, and depress working-class wages. The Democratic response needs to be made in equal and opposite terms. In some cases, this is easy: There have been no terrorist attacks in the U.S. perpetrated by immigrants from the seven Muslim-majority countries Trump included in his original executive order; undocumented immigrants commit crimes at lower rates than American citizens; and so forth.

Things get more complicated when it comes to jobs and wages — and there a fruitful debate about the relative advantages and disadvantages of low- vs. high-skilled immigration for various socioeconomic groups and regions needs to take place.

Most challenging of all is fostering a mutually respectful civic conversation about the relative benefits and harms of allowing high rates of immigration from specific regions, cultures, and religions — not in terms of crime or terrorism, jobs or wages, but in terms of intentionally shaping the ethnic, cultural, and linguistic character of the nation. Explicitly or implicitly affirming humanitarian universalism, many on the left deny the moral legitimacy of having any such conversation at all, since those on the opposing side must be guilty of xenophobia and racism.

But citizens of a political community are allowed to have and express opinions about such issues as whether, for example, the country has admitted a disproportionate number of immigrants from Mexico in recent decades, and to craft policies in response to those opinions. Refusing to engage in the debate and denouncing those on the restrictionist side won't keep it from happening. It will merely ensure that those of us who favor a more cosmopolitan vision of American citizenship and patriotism lose out on the opportunity to make our case.

President Trump has jumpstarted an important and rancorous debate about immigration that is likely to drag on for several years. Democrats are vitally important participants in that debate. But they will be more likely to shape its outcome if they make their case on the merits instead of denying the legitimacy of having the debate in the first place.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

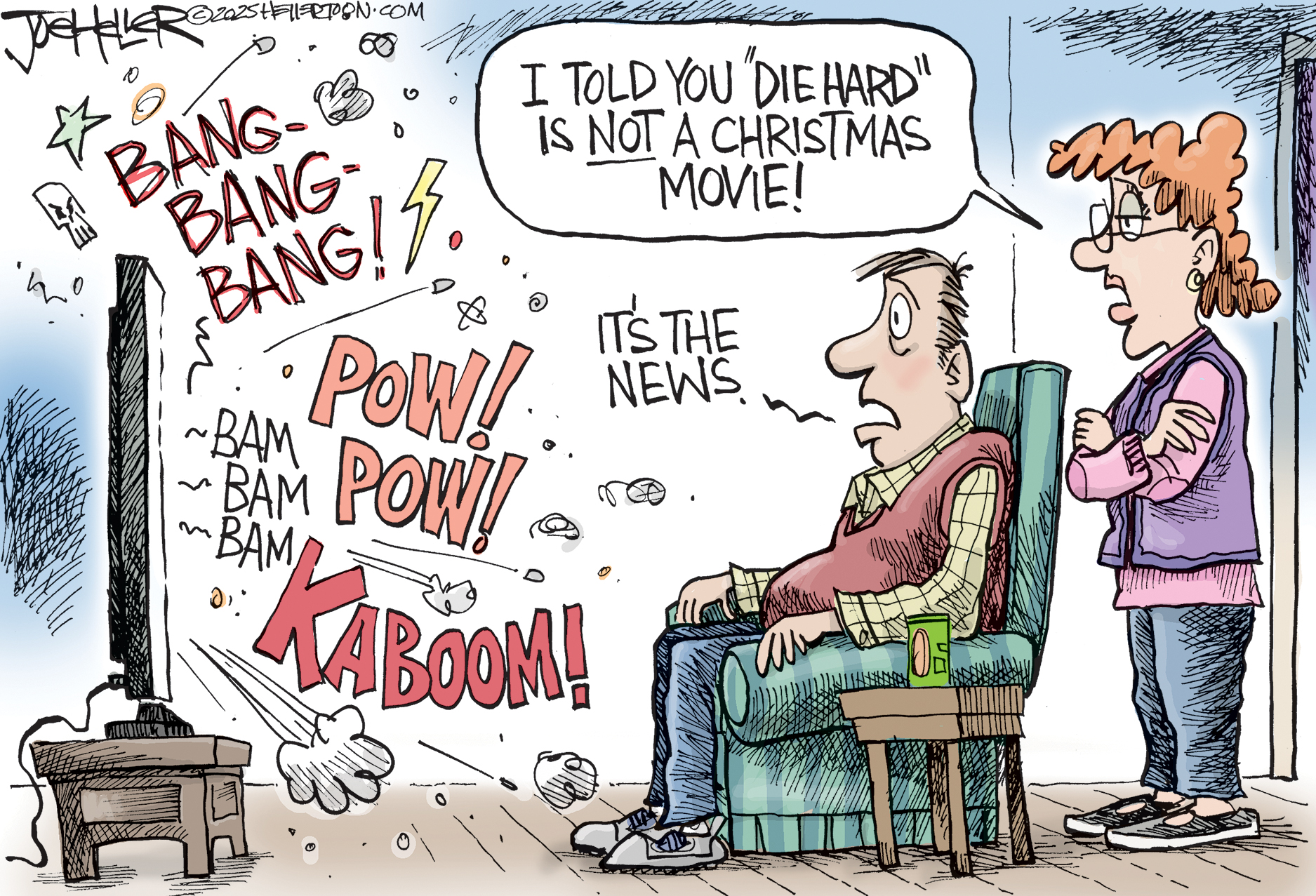

Political cartoons for December 21

Political cartoons for December 21Cartoons Sunday’s political cartoons include Christmas movies, AI sermons, and more

-

A luxury walking tour in Western Australia

A luxury walking tour in Western AustraliaThe Week Recommends Walk through an ‘ancient forest’ and listen to the ‘gentle hushing’ of the upper canopy

-

What Nick Fuentes and the Groypers want

What Nick Fuentes and the Groypers wantThe Explainer White supremacism has a new face in the US: a clean-cut 27-year-old with a vast social media following

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration