How conservatives' choice fetish doomed Paul Ryan's plan to dismantle ObamaCare

Americans don't need more health-care "choice." They need health-care security.

There are many reasons why the Republican plan to "repeal and replace" the Affordable Care Act crashed and burned so spectacularly.

The American Health Care Act managed to alienate GOP moderates and the hard-line libertarian right, not to mention every single Democratic lawmaker in Washington. It antagonized all the major medical lobbies, including the American Medical Association, as well as all the leading conservative think tanks. It was rushed through committees and the Congressional Budget Office, the latter of which predicted it would result in 24 million fewer people covered by insurance. It received rhetorically strong but substantively ill-informed backing from a White House weighed down by low job approval numbers.

But underlying all of these weaknesses was a single, foundational error: House Speaker Paul Ryan's decision to craft and sell the AHCA as a reform that treated "patients as consumers" and sought above all to give them "more choices."

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It's hardly surprising that Ryan took this approach. The right is obsessed with the cost of health care, both for individuals and in the aggregate, and it believes that spending can be most effectively contained by increasing options and competition. That makes choice a means to the end of cost savings. Then there's the fact that the right also makes a fetish of choice for its own sake. It's simply better, apparently, for individuals (acting as consumers) to have more insurance policies, doctors, and hospitals to choose from.

But is more choice always better? When it comes to health care, the answer is often no. What people want isn't choice in medical care, but security. They want to know that when they get sick or suffer an injury they will be able to see a doctor, get medicine, be admitted to a hospital, and receive necessary treatment. They'd also like access to enough preventive care that medical problems can be detected and treated before they become life-threatening. And they would prefer to have all of this without the fear that they'll be bankrupted by the bills.

If the right responds by saying that greater choice is the surest path to achieving these goals, it should at least acknowledge that following that path comes with considerable additional costs.

My colleague Ryan Cooper recently highlighted those costs by way of linking to an old blog post by Bloomberg View economist Noah Smith. In his post, Smith noted that in Tokyo many things Americans assume will be freely available in a city — places to sit down, parks, water fountains — are either off-limits to the public or available only at cost. This creates the need for numerous additional market transactions — and many more choices — than an American is accustomed to.

Does this proliferation of choice produce an improvement in quality of life? The answer is clearly no, because each choice involves a transaction cost — not just a monetary one, but a psychological one as well. In many cases, the costs are small, but they add up. Each choice (Should I pay to enter this park or look for another place to sit? Should I purchase a drink here or hope I find something cheaper before my thirst becomes intolerable?) requires that preferences be ranked, a decision made, and consequences lived with — all of which increases anxiety, and the potential for regrets if the decision proves not to have been a wise one. This is a phenomenon to which social psychologists have devoted increasing attention in recent years, showing that the proliferation of choices in our lives may well contribute to an increase in unhappiness.

Now let's think about how this might play itself out when it comes to the individual market for health insurance.

As options proliferate, individuals face the need to choose among a growing list of high-stakes possibilities. Should I opt for catastrophic coverage that costs less but allows me to see a doctor only if I'm in a severe car accident or suffer a heart attack? Should I purchase something more expensive that will enable me to make an appointment if I'm merely running a fever, worried about the occasional tightness in my chest, or concerned about the mysterious lump in my neck? Or should I take on the enormous medical and financial risk of foregoing coverage altogether?

If I opt for little or no coverage, I'm gambling that I'll be lucky. If I win that bet, the choice will be retrospectively vindicated. But if I'm unlucky, the choice will seem horribly foolish, contributing either to much worse medical outcomes, much worse financial consequences, or both. If, on the other hand, I opt to pay for maximal coverage and I get sick, I'll feel wise. But if I stay healthy, I'll likely end up feeling like a sucker who's wasted enormous resources just to ease my mind.

But of course I can't know any of this in advance, which means that my choices are likely to be fraught with anxiety at the moment I make them — and that anxiety is likely to linger in the background of my life, following me through my days, plaguing me with doubts about my choices. Might I have made a medically and financially catastrophic mistake? Will I regret my choice tomorrow? How about 10, 20, or 30 years from now? Increasing the number of choices before us doesn't address this anxiety. In fact, it makes the anxiety worse.

The right will likely respond that this is life — and what insurance is all about. But that isn't true. It's merely what life is like when health care is treated like a product to be purchased and citizens looking to protect themselves from catastrophe are treated like consumers on the hunt for a good deal.

There is another way — a single-payer system in which access to health care is open to all comers. In such a system, everyone pays in, and everyone is eligible for benefits. Choice has nothing to do with it. Many millions are familiar with precisely such a system because every American over the age of 65 lives with it in the form of Medicare, an enormously popular government program.

The solution to America's health-care woes isn't more choice; it's less. As long as Republicans deny this, they're likely to reenact Paul Ryan's faceplant over and over again.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

By The Week Staff Published

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are the billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are the billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

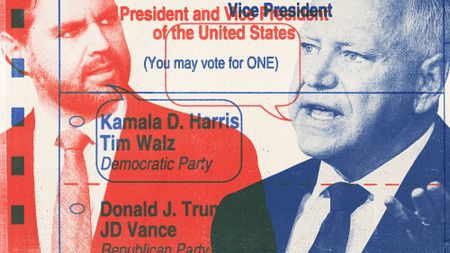

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

The life and times of Kamala Harris

The life and times of Kamala HarrisThe Explainer The vice-president is narrowly leading the race to become the next US president. How did she get to where she is now?

By The Week UK Published

-

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?Today's Big Question 'Diametrically opposed' candidates showed 'a lot of commonality' on some issues, but offered competing visions for America's future and democracy

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published