Why Trump is beating a hasty retreat from populism

The betrayal was inevitable

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It's practically official: The Trump administration is in full retreat from its array of right-wing populist promises.

Instead of scrapping NAFTA, they are merely looking for minor adjustments. Instead of showing China who's boss, they have retreated on Taiwan, and are promising a far more favorable stance on trade in exchange for whatever help China might offer on North Korea — while telegraphing that they know help is bound to be limited. Most dramatically, Trump reversed the overwhelming thrust of his campaign with respect to foreign policy, ordering an attack on Syria and welcoming Montenegro into NATO, saying that the Atlantic alliance is "no longer obsolete." Even if advisor Steve Bannon doesn't lose his job, evidence of his influence is at this point distinctly thin.

But why is Trump beating this retreat? It's not because his new course is more popular. The effort to repeal ObamaCare failed spectacularly in large part because the proposed replacement was obviously inferior, and was wildly unpopular with virtually the entire public. But there is no popular movement clamoring for intervention in Syria, or for the defense of Montenegro. And while the politics of trade are exceedingly complex, with big losers inevitable even if there are also big winners, a committed administration could surely build a case and a constituency for a new trade paradigm. Instead, Trump is rapidly bargaining away his entire agenda.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Are the forces of populism on the wane? From a glance around the world, it doesn't look like it. Take France, where it is increasingly possible, if still less than likely, that the runoff will be a face-off between the National Front's Marine Le Pen and the far left Jean-Luc Mélenchon. If that happens, the established parties — and even novel parties with establishment roots like Emmanuel Macron's En Marche! — would be completely shut out, and France would be certain to be led by a populist of either the left or the right.

But how much would change even if that happened? If the example of Donald Trump's presidency is a caution for right-wing populists, Greece's Syriza should be a caution to those on the left. Elected with an explicit mandate to reject the harsh austerity demanded by the European Union, within months Syriza wound up accepting terms at least as harsh as those they had campaigned against rather than risk an open breach with their German financiers. Capturing the government did not, as it happened, materially change the distribution of power, because that's not where the real power lay. How certain are France's voters that the power to change the terms of their relationship with Europe really lies in the Élysée?

If this is a rule, though, Washington ought to be at least a partial exception. America's military supremacy is arguably unprecedented in world history. The U.S. dollar remains the world's reserve currency. For all the hand-wringing about the decline of American manufacturing, we remain fully capable of producing the vast majority of our strategic materials, and we are more energy independent than we have been in over a generation. Washington should have the capacity to risk reverses that Paris, to say nothing of Athens, cannot.

So why the retreat?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The simplest explanation is that it's a matter of presidential character, or lack thereof. While Trump campaigned as a right-wing populist, he isn't actually a conviction politician, but a vain, lazy celebrity. Faced with any difficult problem, he chooses the easiest way out, which in politics will mean appeasing whoever presents the most current threat. For those of us who pointed out Trump's overwhelming character flaws during the campaign, there is the temptation to say we told you so, and leave it at that.

But we oughtn't to leave it there. For while Washington's national power does give us more latitude to make material policy adjustments than most states, within Washington the exercise of power is not so unconstrained as populists assume.

Presidents don't make foreign policy alone, for example. They rely on the military and on the career diplomatic corps — as well as on policy advisors from the world of think tanks, academia, and the like. All of these people have career advancement to consider, which inevitably shapes their analyses of any given foreign policy problem. It takes considerable sophistication to override those considerations, and in the absence of a clear alternative policy direction, even that sophistication will likely prove inadequate.

Presidents also don't make foreign policy in a global vacuum; other actors on the international stage are fully capable of making their own moves on the chess board in response to — or in anticipation of — our own. Rivals like China and Russia, as well as allies and clients like Japan and Saudi Arabia, will naturally try to manipulate us into situations where they are at an advantage — and they frequently start with an information advantage at a minimum to begin with.

And all of the above have access to the administration's political opposition and the increasingly partisan press to further their particular agendas.

None of that means that policy can't be changed. It means it can't be changed easily, simply by changing leadership at the top. When President Obama sought a nuclear deal with Iran, he faced opposition from all quarters. Allies like Israel and Saudi Arabia were bitterly opposed. Much of the military brass was skeptical, as were a host of foreign policy professionals both outside the government and within his own administration. The deal did finally get done, after years of painstaking work, but it was a close thing, and the ugly compromises along the way that made it possible included supporting Saudi Arabia's brutal war on Yemen.

An even larger reorientation of American foreign and trade policy in an "America First" direction would surely require even greater patience, skill, and determination. These are not character traits generally associated with President Trump. But they are also not the character traits generally associated with populist movements.

Trump's rapid retreat to the path of least resistance does reflect his own callowness, insecurity, and sloth. But it may also reflect the objective correlation of forces. His strongest supporters don't really have anywhere else to turn, because their political movement consisted largely of supporting him. So how will they hold him to account for any betrayal?

That power dynamic won't change until populists stop looking for someone who will speak for them and start organizing to speak for themselves.

Noah Millman is a screenwriter and filmmaker, a political columnist and a critic. From 2012 through 2017 he was a senior editor and featured blogger at The American Conservative. His work has also appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Politico, USA Today, The New Republic, The Weekly Standard, Foreign Policy, Modern Age, First Things, and the Jewish Review of Books, among other publications. Noah lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.

-

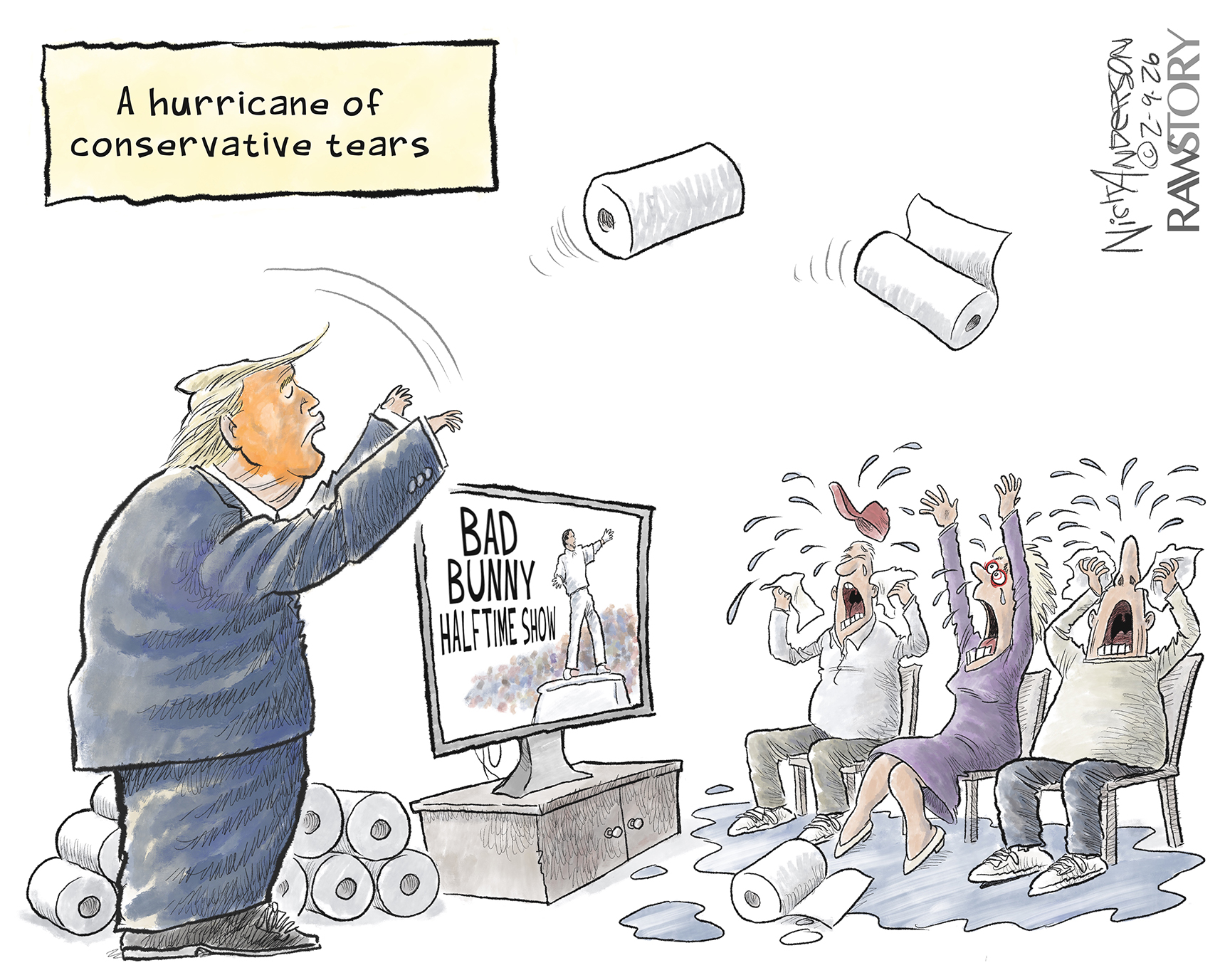

Political cartoons for February 10

Political cartoons for February 10Cartoons Tuesday's political cartoons include halftime hate, the America First Games, and Cupid's woe

-

Why is Prince William in Saudi Arabia?

Why is Prince William in Saudi Arabia?Today’s Big Question Government requested royal visit to boost trade and ties with Middle East powerhouse, but critics balk at kingdom’s human rights record

-

Wuthering Heights: ‘wildly fun’ reinvention of the classic novel lacks depth

Wuthering Heights: ‘wildly fun’ reinvention of the classic novel lacks depthTalking Point Emerald Fennell splits the critics with her sizzling spin on Emily Brontë’s gothic tale

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred