How to make growth great again

Look to the mid-century — and its high rates of public investment and taxation

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The problems with President Trump's new budget are almost too numerous to comprehend. It contains countless cruelties and the most elementary accounting errors. But among economic experts, the big hit on Trump's budget is that it's actually too optimistic: It assumes we'll return to a growth rate of 3 percent.

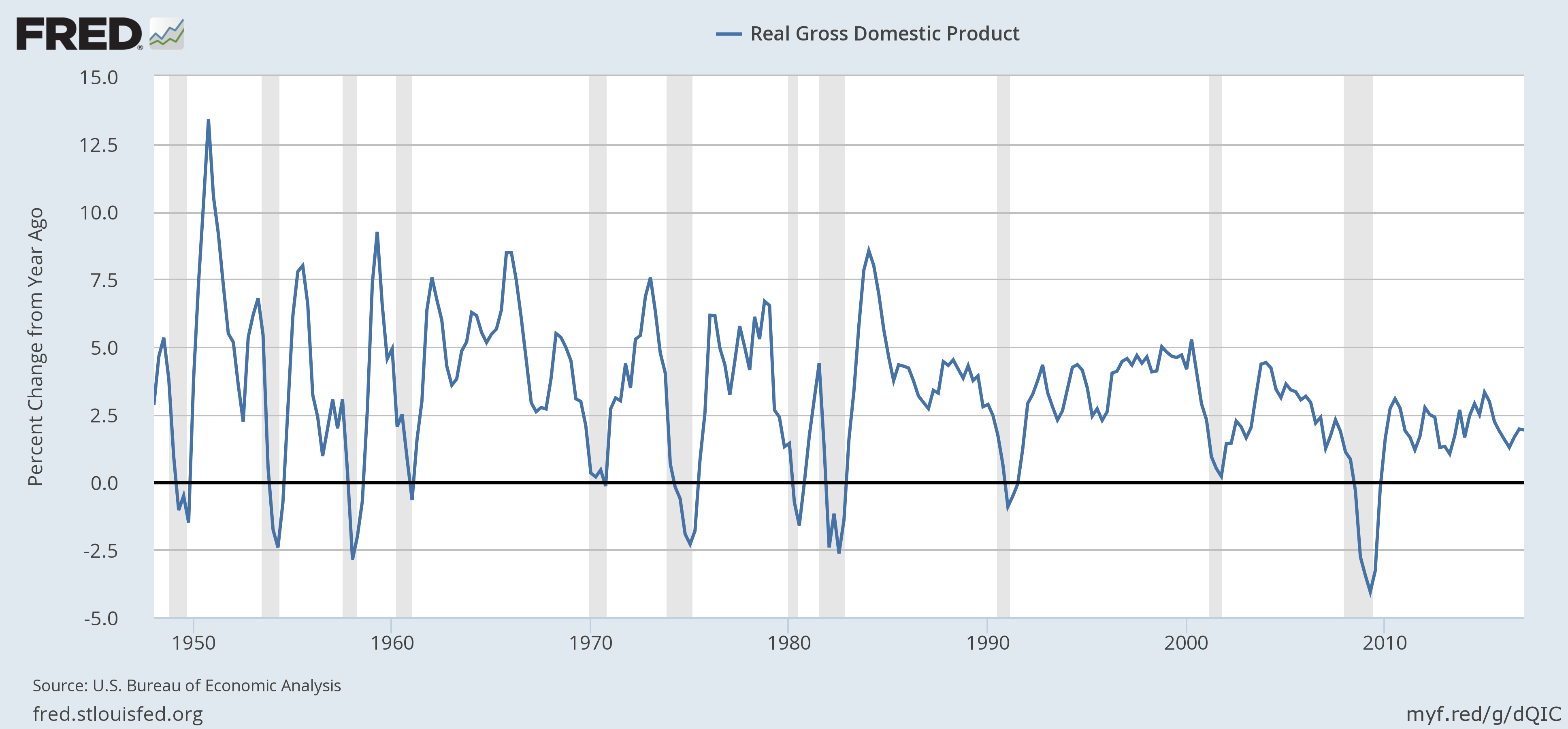

Overly ambitious projections of economic growth from presidential administrations are hardly new. But we averaged 1.8 percent growth over the last decade-and-a-half, and the Blue Chip consensus and the Congressional Budget Office project around 2 percent going forward. As Jason Furman, the former head of President Obama's economic advisers, pointed out, the Trump White House is indulging in a rare level of rosiness here.

At the same time, it's hard not to sympathize with Trump's team when they rage against accepting anemic economic growth as "the new normal." We actually did achieve 3 percent growth for a bit during the 1990s. And before then, back in the 1950s and 1960s, we regularly did quite a bit better. So we know it's possible.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Of course, if we want to get back to those sorts of growth rates, the obvious thing we should ask is: What were we doing then that we aren't doing now?

The answers are also pretty obvious. And they get us to the real problem with Trump's growth forecast: His policy recommendations are the exact inverse of what we were doing in the booming mid-century.

Take taxes: Back in the mid-century, America had a ton of income brackets, and the tax rates on the highest brackets were so overwhelmingly confiscatory they effectively imposed a maximum income on the entire economy.

Then there's public investment: It's hard to overstate how much World War II and Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal set the stage for the prosperity of the '50s and '60s. The government basically set out to employ millions of Americans, first to build everything from dams and bridges to art installations, and then to fuel the American war machine. The Federal Reserve backstopped the government's borrowing with massive money-printing, and then those same tax rates were used to control inflation. All those incomes circulated back into the private economy, leading to a cornucopia of jobs and remarkably low unemployment rates.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The government funded the national highway system, and the G.I. Bill functioned as a massive public investment project, paying for education and housing for millions of Americans. In that era we also launched Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and the war on poverty.

Why did all this matter? Furman notes that economic growth is driven by two factors: Maintaining full employment and keeping productivity growth high.

The mid-century tax rates prevented money from getting dammed up in the financial system and instead forced companies to share more of their profits with workers through higher wages. The flood of jobs made employers compete for workers, which also improved wages and working conditions. That brought us about as close as the country has ever gotten to employing everyone we could possibly employ. Widespread high wages maintained aggregate demand, which created jobs and kept labor markets tight, which in turn kept high wages widespread.

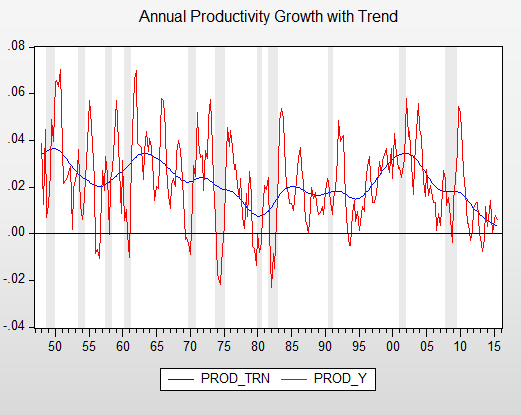

As for productivity, that boils down to businesses doing more with less. And the simplest and most effective way to force businesses to do more with less is to deny them cheap labor. So, not surprisingly, the mid-century is also our historic benchmark for high productivity rates:

Of course, America turned away from the mid-century wisdom well before Trump.

The rise of the business lobby in the 1970s, culminating in Ronald Reagan's presidency, led to massive tax cuts and deregulation. Republicans and Democrats alike spent the 1980s and 1990s abandoning full-employment policies and the fight against inequality. Conventional wisdom settled on the notion that growth was mainly a matter of keeping wealthy investors happy.

Admittedly, we achieved a brief burst of full employment and high productivity in the '90s while balancing the budget. But in retrospect, this was pretty clearly an unsustainable fluke, driven by the stock market bubble. As you can see from the first graph above, the post-Reagan era has been one long slide into stagnation.

What stands out about Trump's budget is how desperately and mindlessly it doubles, triples, and quadruples down on the conventional wisdom, despite decades of failure. Rather than expand public investment, Trump's budget would slash and burn everything in sight, in a self-destructive war against the deficit. It would cut tax rates and reduce the number of brackets still further, showering the bulk of its benefits on the wealthiest.

The deeper problem, though, is how much both parties have forgotten the lessons of history.

That Furman focuses on how unreal Trump's growth projections are only indicates the limits of the modern liberal imagination. We certainly don't want another world war, but there are plenty of other ambitious employment projects we could take on. Mainstream Democrats may finally be realizing this: Their flagship think tank, the Center for American Progress, recently proposed a "Marshall Plan" for the U.S. economy. But they still have a ways to go.

Yet while the Democratic Party implicitly accepted the "new normal," the GOP did something much worse: It embraced a mutant optimism that would destroy the U.S. economy in the name of saving it — largely because doing so would benefit the Republicans' wealthy donor base.

To really push back against the economic vision of the Trump White House will require avoiding both mistakes.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

6 exquisite homes with vast acreage

6 exquisite homes with vast acreageFeature Featuring an off-the-grid contemporary home in New Mexico and lakefront farmhouse in Massachusetts

-

Film reviews: ‘Wuthering Heights,’ ‘Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,’ and ‘Sirat’

Film reviews: ‘Wuthering Heights,’ ‘Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,’ and ‘Sirat’Feature An inconvenient love torments a would-be couple, a gonzo time traveler seeks to save humanity from AI, and a father’s desperate search goes deeply sideways

-

Political cartoons for February 16

Political cartoons for February 16Cartoons Monday’s political cartoons include President's Day, a valentine from the Epstein files, and more