Morality in the age of sex robots

Liberalism is going to need a new toolbox

If you think that the world today is a much better place than it was 50 or 60 years ago, consider the fact that, as I write this, there is a man in Japan whose company sells robotic sex dolls meant to simulate the experience of raping a child.

Shin Takagi, whose products have been routinely seized by customs authorities in the United Kingdom and Australia, is a self-proclaimed pedophile, albeit one who says he has never harmed a child.

"We should accept that there is no way to change someone's fetishes," he told The Atlantic in an interview last year. "I am helping people express their desires, legally and ethically. It's not worth living if you have to live with repressed desire." He insists that if he had not been allowed to perform repeated acts of self-abuse in the presence of his youthful androids, he would now be a rapist.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It is worth pointing out that Takagi's optimistic view of the quasi-therapeutic use of his products — or, as he insists, works of art — are generally dismissed in the mainstream robotic sex community. "Treating pedophiles with robot sex-children is both a dubious and repulsive idea," Professor Patrick Lin of California Polytechnic Luis Obispo, an expert in "robotic ethics," recently told the Telegraph of London.

The fact that raping kids is wrong even if it's just make believe! is an actual point that needs to be addressed by a credentialed academic in an obscure discipline might seem depressing. But I cannot help but take it as a sign of hope.

Perhaps without realizing it, Lin has pulled the rug out from under higher liberalism, that alliance of progressives who think there is a connection between people doing what they want with their private parts and economic justice, cynical neoliberals, #woke capitalists, and libertarian absolutists. For adherents of the higher liberalism, all moral questions can be decided with reference to the so-called "harm principle" of John Stuart Mill, according to which nothing can be considered immoral — and therefore subject to legal penalty — if it does not inflict injury upon a person other than whoever is responsible for the action in question. It is a simple, elegant, and hysterically wrong-headed argument that is nevertheless difficult to refute.

Part of this is because it is difficult to arrive at a broadly agreed upon definition of what exactly constitutes "harm." Surely bodily injury in the strict sense cannot be the limit. Everyone, even those who do not believe in the soul, acknowledges that there is such a thing as psychological harm. But generally the view of what is morally licit ends up coming down to whether or not two or more adults consent to a given course of action: fornication, sodomy, adultery, appearing in humiliating pornographic videos. (It is generally admitted that there are certain things — cannibalism, for instance — that no one can ever consent to, though an earnest libertarian did once admit to me that he had no problem with someone signing a contract during his lifetime stipulating that his body was to be given to necrophiliacs in exchange for a sum of money.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Which brings us back to kid sex robots. In this case, there is no issue of anyone, a child or otherwise, being subjected to bodily harm in the strict sense. Nor is there any party to whom consent must be given. It ought, according to standard harm-principle reasoning, be a straightforward case of Let 'er rip!.

Yet one imagines that Lin speaks for most people when he says that this cannot be countenanced. One could say that this is because it is possible that indulging in these appetites in an ostensibly harmless manner will sooner or later encourage pedophiles to seek out the real thing. But I doubt it.

The truth is that all of us at some level or another understand as if by instinct that certain desires are in and of themselves wrong. They should not be acted upon, placated, appeased, or in any sense met halfway. Most of us, one hopes, feel this way about pedophilia and bestiality (how far away are we, I wonder, from dog sex robots?), at the very least. It is the moral duty of people who want to hurt children or animals to banish such desires from their mind, to seek help, to pray — to do whatever it takes to ensure not only that they never carry out their fantasies but that they no longer have them. "Acting upon them" is beside the point; that anyone anywhere is contemplating such things is inherently evil.

Once this truth is acknowledged and it is accepted that certain impulses are immoral not simply because they have potential to lead to others' being harmed but because they are in themselves wicked, it becomes much more difficult to make the usual facile arguments in favor of everything from legalized marijuana to secular liberals' redefinition of marriage. The argument is no longer about abstract "harm" but about those old stalwarts good and evil.

Liberalism is going to need a new toolbox.

Matthew Walther is a national correspondent at The Week. His work has also appeared in First Things, The Spectator of London, The Catholic Herald, National Review, and other publications. He is currently writing a biography of the Rev. Montague Summers. He is also a Robert Novak Journalism Fellow.

-

‘It is their greed and the pollution from their products that hurt consumers’

‘It is their greed and the pollution from their products that hurt consumers’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Jane Austen lives on at these timeless hotels

Jane Austen lives on at these timeless hotelsThe Week Recommends Here’s where to celebrate the writing legend’s 250th birthday

-

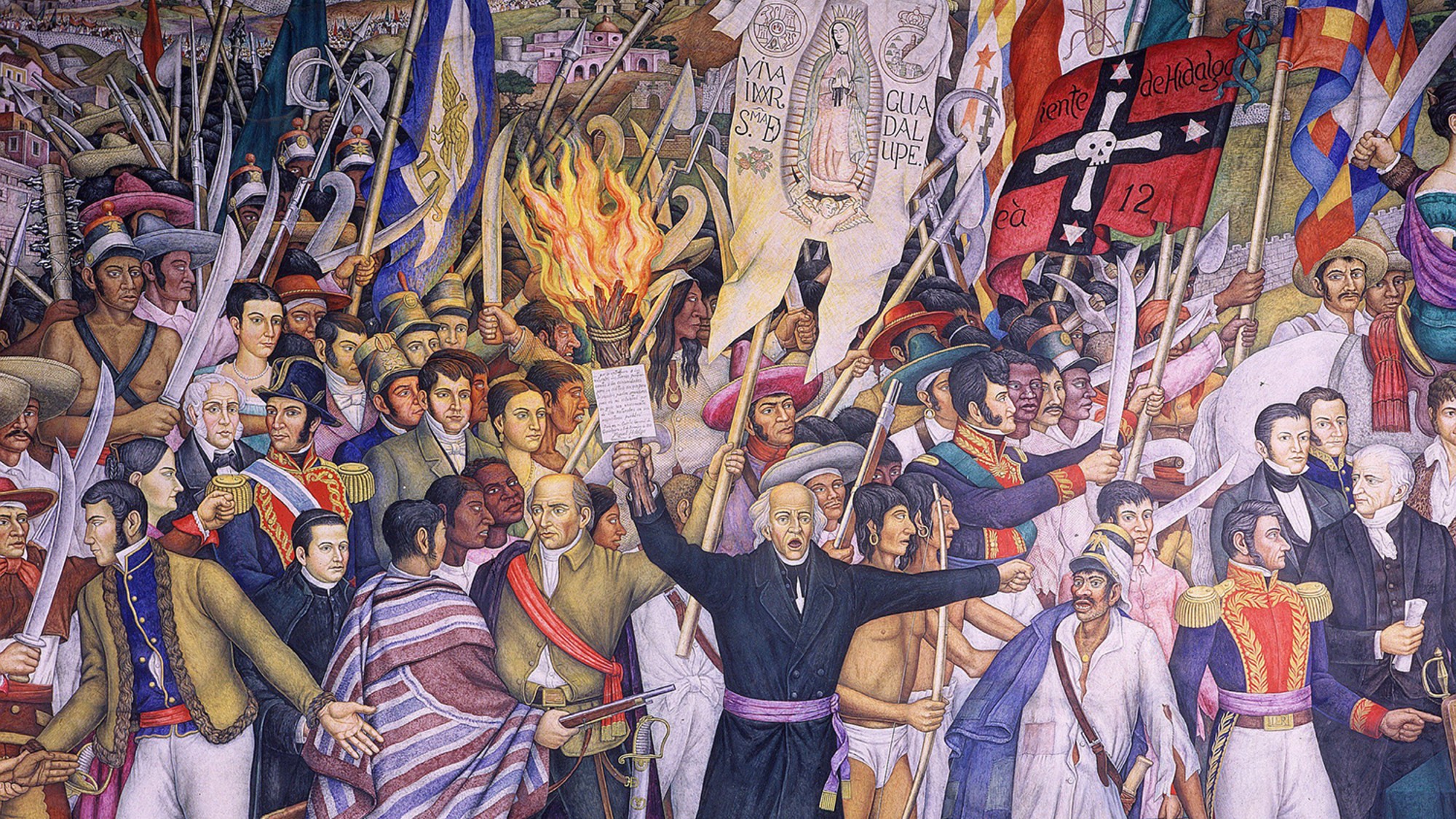

‘Mexico: A 500-Year History’ by Paul Gillingham and ‘When Caesar Was King: How Sid Caesar Reinvented American Comedy’ by David Margolick

‘Mexico: A 500-Year History’ by Paul Gillingham and ‘When Caesar Was King: How Sid Caesar Reinvented American Comedy’ by David Margolickfeature A chronicle of Mexico’s shifts in power and how Sid Caesar shaped the early days of television

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration