Scientists want to fight malaria by poisoning mosquitoes with human blood

Drugging the bugs

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Scientists may have found a solution to stop the spread of malaria: poisoning mosquitoes with human blood. New research suggests that the mosquito-borne malady can be curbed by getting the insects to consume the drug nitisinone. As malaria and other illnesses spread by mosquitoes become increasingly prevalent, nitisinone could help to reduce infections worldwide.

Brandishing the blood

Nitisinone can make human blood incredibly toxic to mosquitoes, according to a study published in the journal Science Translational Medicine. The research showed that the insects "die within a few hours of feeding on samples from patients who received even relatively low doses," said National Geographic. "What's more, the drug remains effective for up to 16 days after the initial dosing."

The drug is typically used to treat rare genetic disorders like alkaptonuria and tyrosinemia type 1. Nitisinone blocks the enzyme 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase in the body. "While this helps patients with metabolic disorders, it disrupts digestion in mosquitoes that drink the blood of medicated individuals — ultimately killing them," said Interesting Engineering. The drug can cause side effects in humans — but the people with these rare disorders "typically have to take much higher quantities of the drug than would be needed for effective mosquito control," said National Geographic.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Nitisinone is not a preventative medication for malaria. But "by killing the mosquitoes before they can lay eggs, the drug might be able to knock down disease-transmitting mosquito populations to the point that it breaks the chain of infection," said National Geographic.

Double drugs

Ivermectin is another drug that is toxic to mosquitoes. It rose to fame following the false claim that it could treat Covid-19, but has long been used to kill the pesky insects. However, it can also be environmentally toxic, and resistance to the drug "becomes a concern" when it is "overused to treat people and animals with worm and parasite infections," said a news release. By contrast, nitisinone "specifically targets blood-sucking insects, making it an environmentally friendly option," said Alvaro Acosta Serrano, a professor of biological sciences at Notre Dame and co-corresponding author of the study.

In addition, nitisinone is faster acting than ivermectin. "While ivermectin given to humans or cows can kill mosquitoes at lower concentrations than nitisinone, the new drug acts more quickly, often within a day," and it "does not target the nervous system, so it is less neurotoxic," said Science Alert. Ideally, "it could be advantageous to alternate both nitisinone and ivermectin for mosquito control," Lee R. Haines, an associate research professor of biological sciences at the University of Notre Dame, honorary fellow at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and co-lead author of the study, said in the news release. "For example, nitisinone could be employed in areas where ivermectin resistance persists or where ivermectin is already heavily used for livestock and humans."

Climate change is expanding the range of mosquitoes, which allows for mosquito-borne diseases like malaria to spread wider. This makes it all the more important to take preventative measures. "You have more bites, more areas where they're able to live, more months when they're active, and more places for them to breed," Matthew Phillips, a research fellow in infectious diseases at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, said to the Harvard Gazette. "That means larger populations."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in Iraq

The President’s Cake: ‘sweet tragedy’ about a little girl on a baking mission in IraqThe Week Recommends Charming debut from Hasan Hadi is filled with ‘vivid characters’

-

Kia EV4: a ‘terrifically comfy’ electric car

Kia EV4: a ‘terrifically comfy’ electric carThe Week Recommends The family-friendly vehicle has ‘plush seats’ and generous space

-

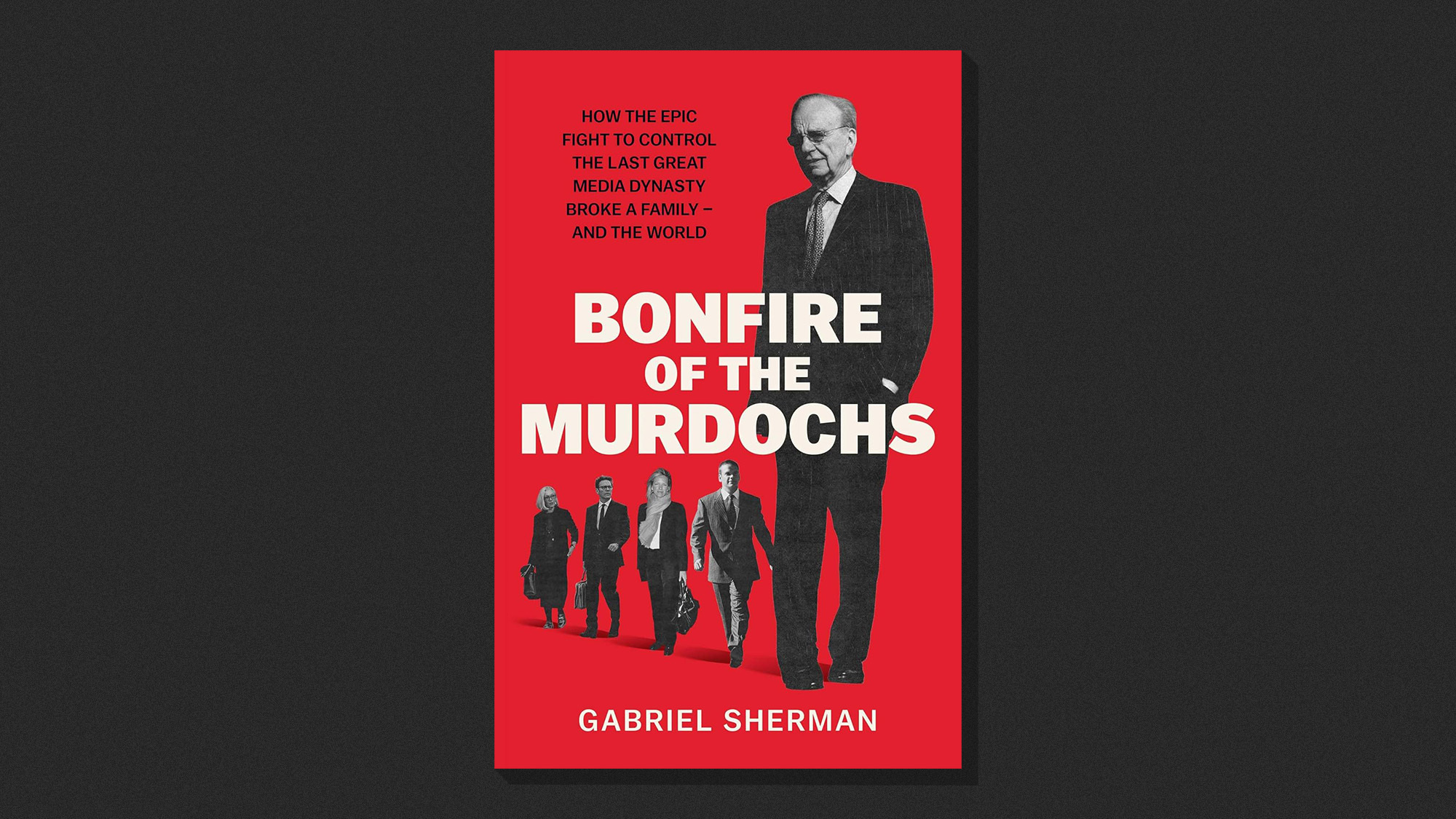

Bonfire of the Murdochs: an ‘utterly gripping’ book

Bonfire of the Murdochs: an ‘utterly gripping’ bookThe Week Recommends Gabriel Sherman examines Rupert Murdoch’s ‘war of succession’ over his media empire

-

AI surgical tools might be injuring patients

AI surgical tools might be injuring patientsUnder the Radar More than 1,300 AI-assisted medical devices have FDA approval

-

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific research

How roadkill is a surprising boon to scientific researchUnder the radar We can learn from animals without trapping and capturing them

-

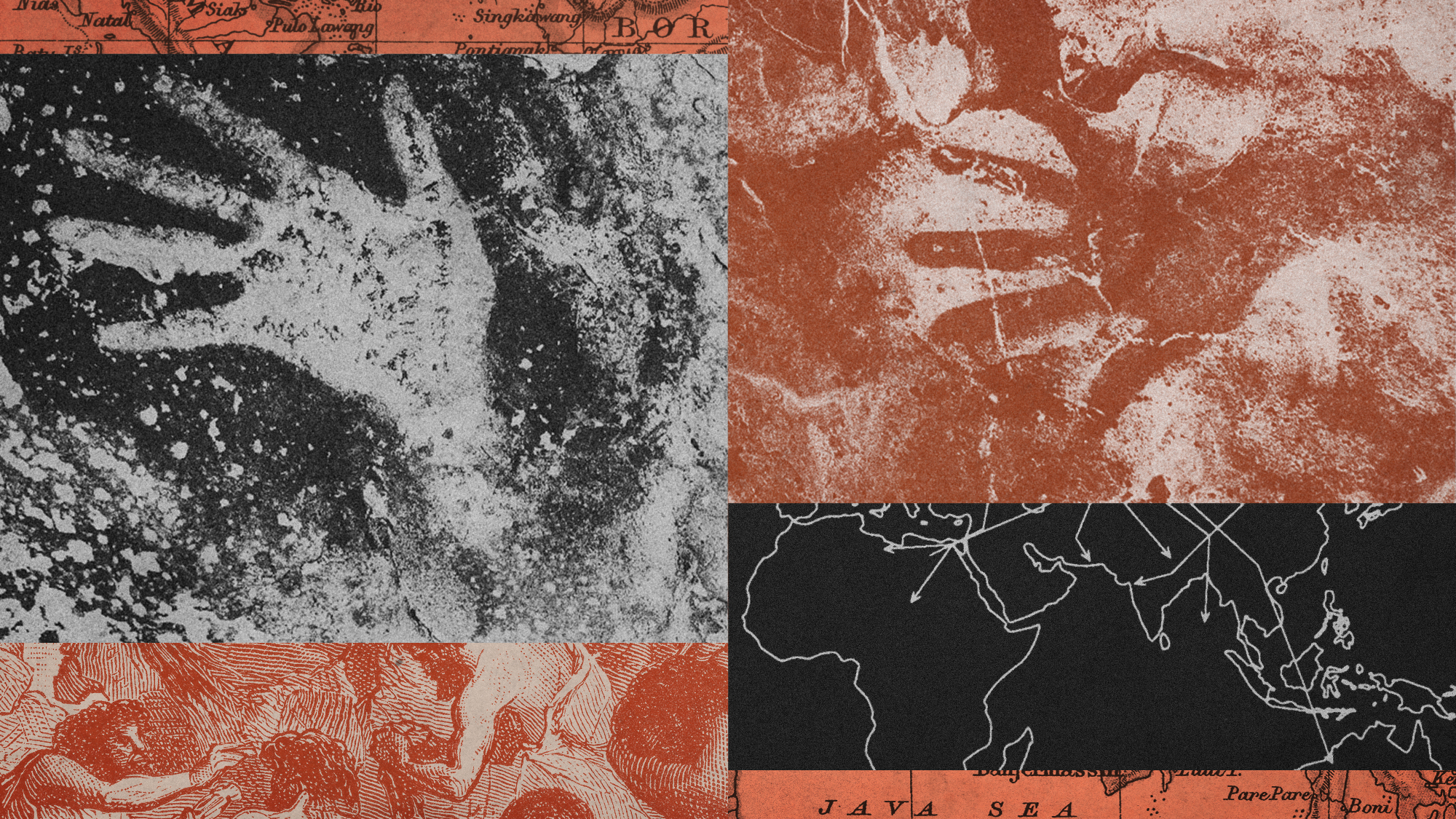

The world’s oldest rock art paints a picture of human migration

The world’s oldest rock art paints a picture of human migrationUnder the Radar The art is believed to be over 67,000 years old

-

Moon dust has earthly elements thanks to a magnetic bridge

Moon dust has earthly elements thanks to a magnetic bridgeUnder the radar The substances could help supply a lunar base

-

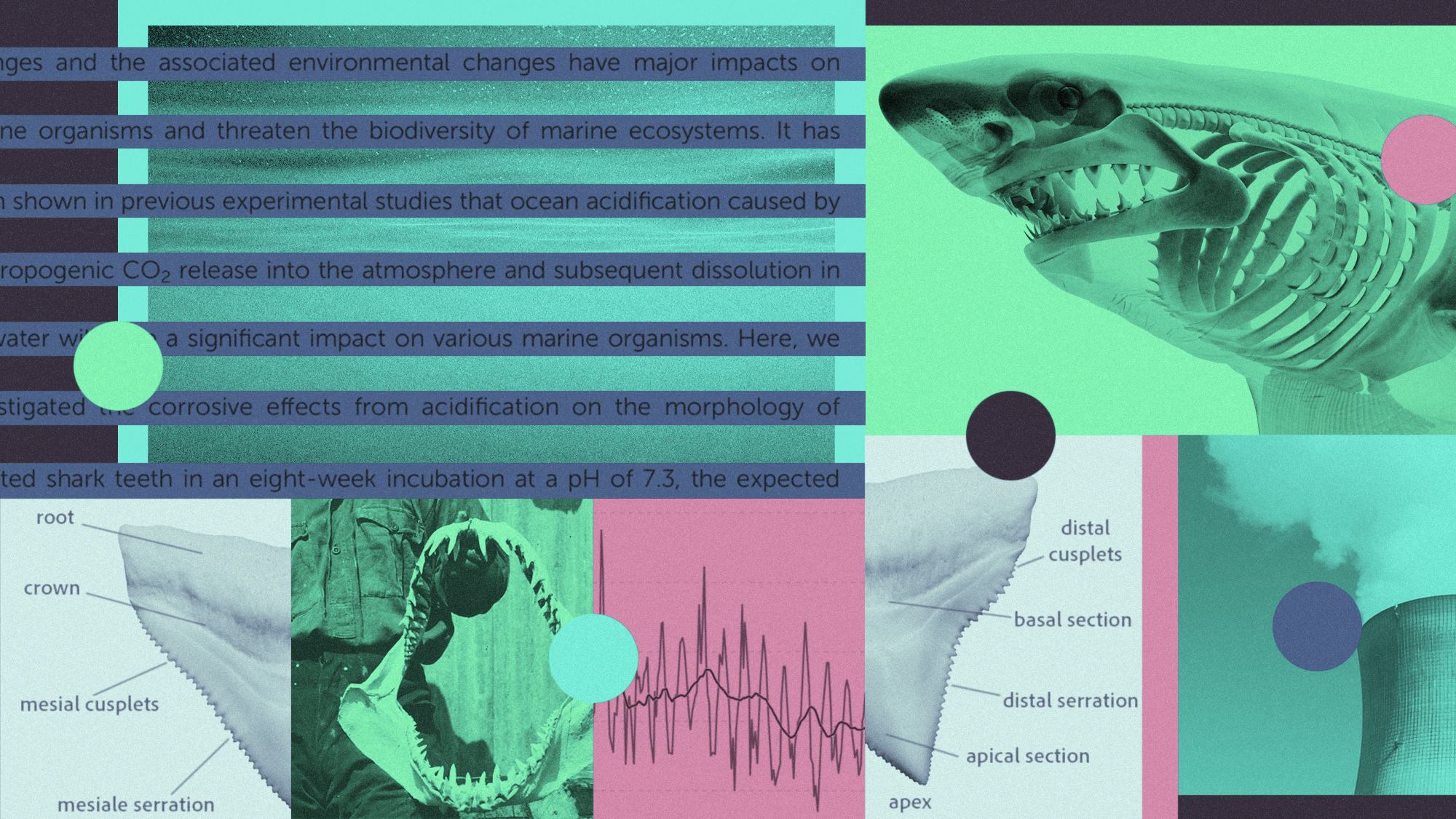

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teeth

The ocean is getting more acidic — and harming sharks’ teethUnder the Radar ‘There is a corrosion effect on sharks’ teeth,’ the study’s author said

-

The Iberian Peninsula is rotating clockwise

The Iberian Peninsula is rotating clockwiseUnder the radar We won’t feel it in our lifetime

-

The ‘eclipse of the century’ is coming in 2027

The ‘eclipse of the century’ is coming in 2027Under the radar It will last for over 6 minutes

-

NASA discovered ‘resilient’ microbes in its cleanrooms

NASA discovered ‘resilient’ microbes in its cleanroomsUnder the radar The bacteria could contaminate space