How America's judges became feudal lords

It's time to hold the federal judiciary accountable

"What kind of person wants to have the same identical job for 35 years?"

For decades, activists across the political spectrum have debated whether the federal judiciary should have term limits. But the above question, recently posed in the hypothetical by retired judge Richard Posner, reveals how the jurists themselves may grow fatigued in their work.

The argument over lifetime appointments pits the need for detachment from politics in judicial decisions against the need for accountability for public officials. Thus far, the concern over political manipulation has outweighed the demands for oversight at the federal level, and no such term limits exist, though many states require specific terms of office and voter retention elections for judges at the district and appellate level.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But in an "exit interview" with The New York Times, Posner, a Reagan appointee who recently retired from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, inadvertently revealed how lifetime appointments can eventually make for sloppy judging. Speaking to the Times' Adam Liptak, Posner said that the long tenure since his 1981 appointment had worn him down to the point that his interest in the case work had waned. "I started asking myself, what kind of person wants to have the same identical job for 35 years?" Posner recalled about his decision to retire. "And I decided 35 years is plenty. It's too much. Why didn't I quit 10 years ago?"

Most disconcertingly, Posner told Liptak that one consequence of his long tenure was that he stopped worrying much about what the law said, or even how the Supreme Court had set precedent. "I pay very little attention to legal rules, statutes, constitutional provisions," said Posner, a prolific jurist, about his work in the federal judiciary. "A case is just a dispute. The first thing you do is ask yourself — forget about the law — what is a sensible resolution of this dispute?"

Forget about the law? If that strikes readers as arrogance, it only means their antennae are well tuned to it. In a single sentence, Posner validated the concerns that conservatives have had with the federal judiciary for decades. The job description he had developed for himself late in his 35-year run on the appellate bench equates more to a feudal lord than a public official in a self-governing republic, and it precisely aligns with the conclusion reached by more and more Americans that their government and the law have become captive to unaccountable elites.

The role of the judiciary in the American model of governance certainly can be described as dispute resolution — but within the law. At both the federal and state levels, voters elect representatives to legislatures, which write the laws under which we consent to be governed. The executive branch provides a check on that authority with veto power and enforces the laws that are by common agreement adopted. The judiciary has the authority to rule when laws violate federal and state constitutions, but their primary role is to use the law to either guide trials to just conclusions or to review cases on appeal — in the context of settled law and precedent.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The guiding principle of this system, imperfect as it can be, is due process under the law for everyone, regardless of rank or privilege. The end result should be a predictable system by which citizens in all situations can rely on both law and precedent to guide their decisions. The entire philosophy of judicial precedent, called stare decisis, is designed to keep the judicial branch from issuing rulings based on personal preference, bias, and flat-out whimsy.

That, unfortunately, precisely describes Posner's late-career approach. Posner speaks with derision about Supreme Court rulings and precedent, describing them as obstacles to his own whims. "When you have a Supreme Court case or something similar," Posner told Liptak, "they're often extremely easy to get around." Posner has even less regard for critics of his approach: Some, he allowed, are sincere believers in a "formalist tradition," but others are simply "reactionary beasts … who want to manipulate the statutes and the Constitution in their own way."

Remarkably, Posner said so without any hint that he grasps the irony of his complaint. One man's reactionary beast is another man's superior intellect — or the kind of unpredictable outcomes from which the rule of law is supposed to protect Americans.

Just how long did Posner ignore the law in favor of his own preferences? He described his exhaustion as having begun "10 or 15 years" prior to his retirement. But that question is entirely academic; there is no way to go back and relitigate those cases and undo any damage Posner did. Even if Posner was still on the court, a solution would be almost impossible short of impeachment and removal by Congress, a remedy rarely applied and usually only in cases of outright corruption.

The better question to ask is how many other Posners we may have on the bench. That should prompt us to seriously discuss how to prevent them from elevating themselves to star-chamber status, and demand accountability on the terms of the governed.

Our founders created this nation to distance themselves from actual feudal lords and force regular accountability on our leaders. It's time to bring that same accountability to the federal judiciary.

Edward Morrissey has been writing about politics since 2003 in his blog, Captain's Quarters, and now writes for HotAir.com. His columns have appeared in the Washington Post, the New York Post, The New York Sun, the Washington Times, and other newspapers. Morrissey has a daily Internet talk show on politics and culture at Hot Air. Since 2004, Morrissey has had a weekend talk radio show in the Minneapolis/St. Paul area and often fills in as a guest on Salem Radio Network's nationally-syndicated shows. He lives in the Twin Cities area of Minnesota with his wife, son and daughter-in-law, and his two granddaughters. Morrissey's new book, GOING RED, will be published by Crown Forum on April 5, 2016.

-

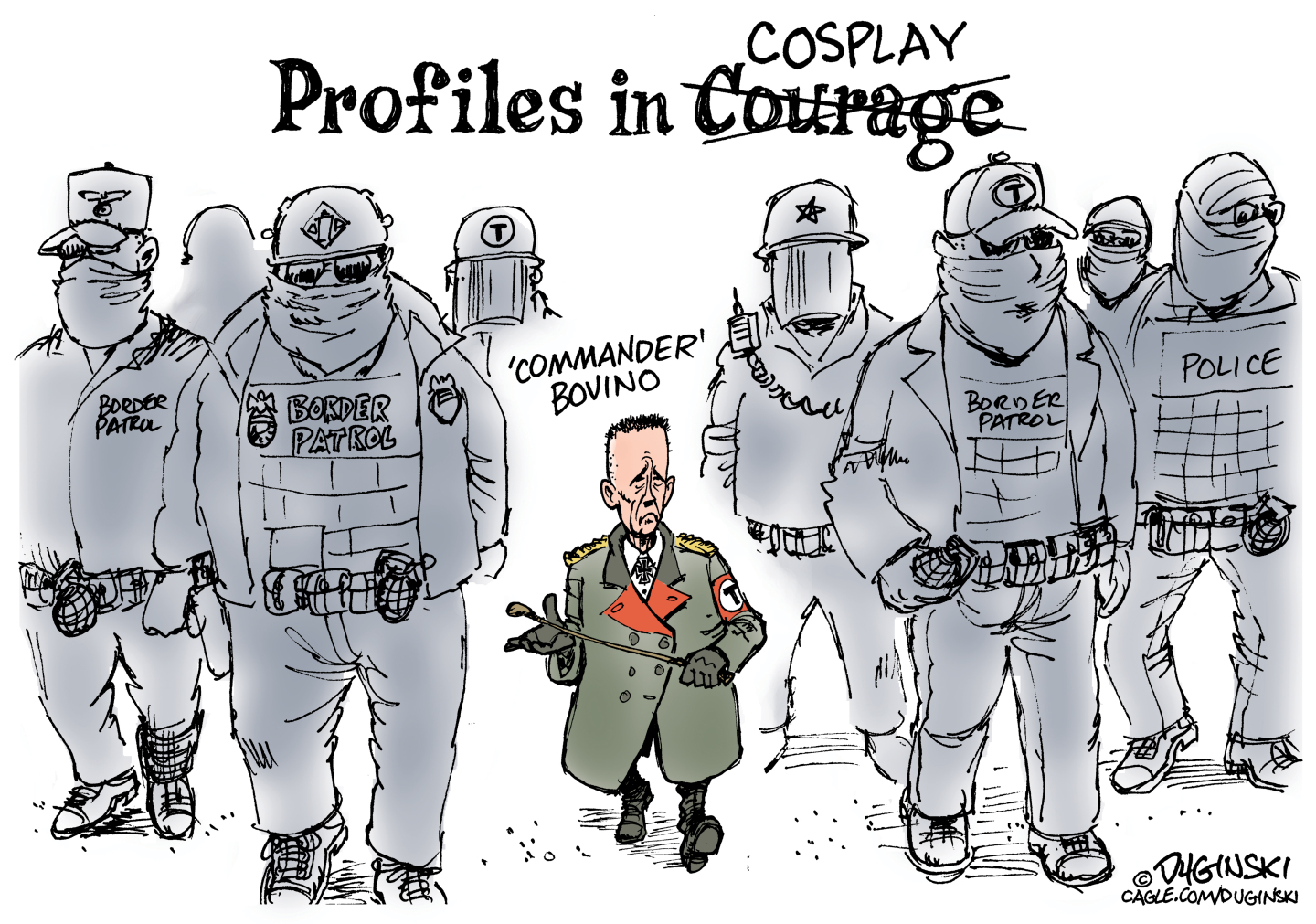

Political cartoons for January 20

Political cartoons for January 20Cartoons Tuesday's political cartoons include authoritarian cosplay, puffins on parade, and melting public support for ICE

-

Cows can use tools, scientists report

Cows can use tools, scientists reportSpeed Read The discovery builds on Jane Goodall’s research from the 1960s

-

Indiana beats Miami for college football title

Indiana beats Miami for college football titleSpeed Read The victory completed Indiana’s unbeaten season

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred