Neil Finn's ageless wonder

Reflections on the chilliness and beauty of Neil Finn's Out of Silence

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

All too many pop stars have trouble figuring out how to age gracefully.

After all, since the dawn of the rock era, pop music has been a genre primarily by and for young people. That has remained true even as some of the biggest stars from its first two decades have blown through middle age to reach their 70s. There's something faintly ridiculous about a geriatric Rolling Stones or Blondie going out on stage to grind out salacious hits from decades ago, as if Mick Jagger and Debbie Harry weren't now in significant danger of falling over and breaking a hip in front of an audience of thousands.

Neil Finn's band Crowded House never reached such stratospheric levels of fame in the U.S., where the group is mainly known for its debut hit single from 1986, the ballad "Don't Dream It's Over," which has become something of a latter-day pop standard. In much of Europe, Australia, and Finn's native New Zealand, the band was much bigger, selling roughly 10 million records and becoming known as a worthy successor to The Beatles in crafting melodically sophisticated pop singles. (More than one critic has drawn parallels between Finn's best tunes and those of Paul McCartney at his early peak.) Finn's solo career and records with his brother Tim Finn have also enjoyed commercial success Down Under.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Finn is now 59, but he's always had something of an old soul. Crowded House's self-titled debut album was chock full of tuneful, catchy songs, but a few showed glimpses of the darkness that came to the fore on the band's sophomore effort Temple of Low Men from 1988. Now the songs began with verses in moody minor keys or moved through disorienting shifts in tonality before finally reaching gloriously uplifting choruses. It was all tension and release — a harmonic version of the quiet verse/loud chorus dynamic that came to define grunge a few years later. As time has passed, Finn's songs have grown progressively darker, with a little more tension and a little less release on every record.

The trend reaches a culmination of sorts on Finn's new album, Out of Silence. Most of the record was recorded live in the studio in one four-and-a-half-hour session that was streamed live online on Aug. 25, with digital files available for purchase seven days later. (CDs will be released in the U.S. on Oct. 6.)

The sessions were fascinating to watch, but recording the album this way was also an awkward match for this material. A live-in-the-studio experiment would seem to be best suited to an improvisational approach in which each take of a song is allowed to develop organically in subtly different directions. Yet this record has what may be the most meticulous (and scrupulously rehearsed) arrangements of Finn's career — along with instrumentation furthest removed from the informality of rock's ubiquitous guitars, bass, and drums.

Drums appear on just two of its economical 10 songs. Electric bass can be heard on just a handful of tracks. If there's electric guitar, it's imperceptible. In its place we have subtle, complex arrangements for strings, brass, woodwinds, and a 12-person choir, as well as acoustic guitar and Finn's own piano and vocals. In its musical ambition and complexity, Out of Silence somewhat resembles Elvis Costello's The Juliet Letters, the 1993 album on which the once-punky bad boy of the New Wave implausibly teamed up with the Brodsky Quartet to produce a classically infused song cycle for string quartet and voice.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Finn's new album isn't quite that unorthodox, but it is filled with challenging music that pushes hard at the boundaries of rock. Many of its songs have as much in common with Franz Schubert's Lieder as they do with the all-too-perfect team-built synthetic pop confections that typically top the charts in 2017. There are moments of unadulterated beauty here — especially on the album's first two songs, the luminescent "Love Is Emotional" and the hymn-like "More Than One of You." But most of the remaining tracks resemble a chilly walk in the woods on a cloudy fall afternoon, with minor keys and major-seventh chords casting shadows on a landscape of muted colors. The clouds invariably break for brief bursts of life-giving sunshine and warmth in the form of a few fleeting measures of major-chord resolution. But just as surely the clouds return, along with the shadows.

This is emphatically adult music, written and performed by a great songwriter well into middle age and eager to share bittersweet wisdom, hard won over the course of a life now well over halfway done.

Most of the album turns inward, to the heartache and struggles of a lifelong marriage ("Love Is Emotional," "I Know Different"), to the toll exacted by black moods ("Chameleon Days"), to the plague of loneliness ("Alone"). But Finn also takes stock of a troubled world, reflecting on the human cost of war ("Widow's Peak"), police brutality ("The Law Is Always On Your Side"), and terrorism ("Terrorize Me").

Regardless of his subject, Finn and the characters he writes about are haunted by death and the difficulty of accepting our powerlessness before the inevitable. The moody soul who nearly breaks his thumb punching a wall in "Chameleon Days" pronounces, "Anyone could tell you / That it's out of your hands / God is rolling numbers / While you're making a plan." "Independence Day," a melancholy meditation on finitude that could be an excerpt from Ecclesiastes, opens with the lines, "As it was in the beginning / So it will be in the end," and reaches a climax with the pronouncement that "One day it's over / Like it never happened / Disappeared without a trace." The narrator of "Alone," suffering in solitude in a "city 10 million strong," describes himself as "Lonely as a body / Left behind when souls have fled."

On "Second Nature," the most upbeat and straightforwardly tuneful track on the album, a man admires a beautiful couple speeding around a corner on a Vespa and is prompted to reflect on his own timidity and indecisiveness: "How many days that you waste as you make up your mind / Freaking out with the knowledge that everyone dies" — at which point a chorus of background singers mocks his pretense to honesty: "You don't believe it."

The album culminates in two expressions of defiance, one public, the other emphatically private. "Terrorize Me," lyrically the most accomplished song on the record, responds to the Bataclan attack in Paris, which killed 89 and injured 413 at a rock concert in November 2015, by reminding us that for the perpetrators "music is an evil force." Pondering the carnage, Finn wonders how he might respond when "there are no words" to capture the evil of their act. Then he hits on an idea:

In my distant homeI will write a melodyThat I will sing for you when I returnIt may not change a lotBut I'll give it everything I've gotIt will come to lifeBecause of you

In their horrific act of violence directed against people gathered to enjoy an evening of music, the terrorists inspired Finn to write the mournfully beautiful melody of this very song. From death comes life, and in that affirmation the terrorists' aims are defeated.

The album's concluding track, "I Know Different," may be its most moving — an impressionistic portrait of a long-term relationship pulled back from the brink of dissolution, with an achingly sad melody delicately sung over piano and strings and backed by an angelic chorus. A spouse worries about her partner's distance and emotional darkness as she watches him search for peace alone on a wild beach, "Just staring out to sea … / A silhouette against the ocean spray."

Eventually the gloom lifts, as the man surrenders to the "rhythmic tide / That pushes darkness out and shows in light." The turning of the emotional tide gives him the resolution to own up to the hurt he's caused the person he loves, as well as to offer a pledge to "stay with you, if you'll let me." He and his partner "came close up / To believing that we're through," but the man no longer thinks so. "I know different," he asserts reassuringly in the record's final line.

Will the reconciliation last? We'd like to think so. Yet as Finn declares in a song earlier on the album, "The world will never change." The tides will ebb and flow, darkness and light will succeed one another, in our moods no less than in the world in which we live out our days against a backdrop of certain annihilation. Every reconciliation is destined to issue in another falling out, each confident proclamation of knowledge to dissolve into renewed doubt, as the circle begins again.

The words "out of silence" do not appear in any of the album's songs, which renders its title somewhat mysterious. It seems fitting to think of the phrase as offering a musical variation on the biblical line about human beings originating from and eventually returning to dust: From out of silence we come, and to silence we shall return. But while we're here, let us sing about our sorrows and struggles no less than our joys.

Neil Finn does exactly that on Out of Silence.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

El Paso airspace closure tied to FAA-Pentagon standoff

El Paso airspace closure tied to FAA-Pentagon standoffSpeed Read The closure in the Texas border city stemmed from disagreements between the Federal Aviation Administration and Pentagon officials over drone-related tests

-

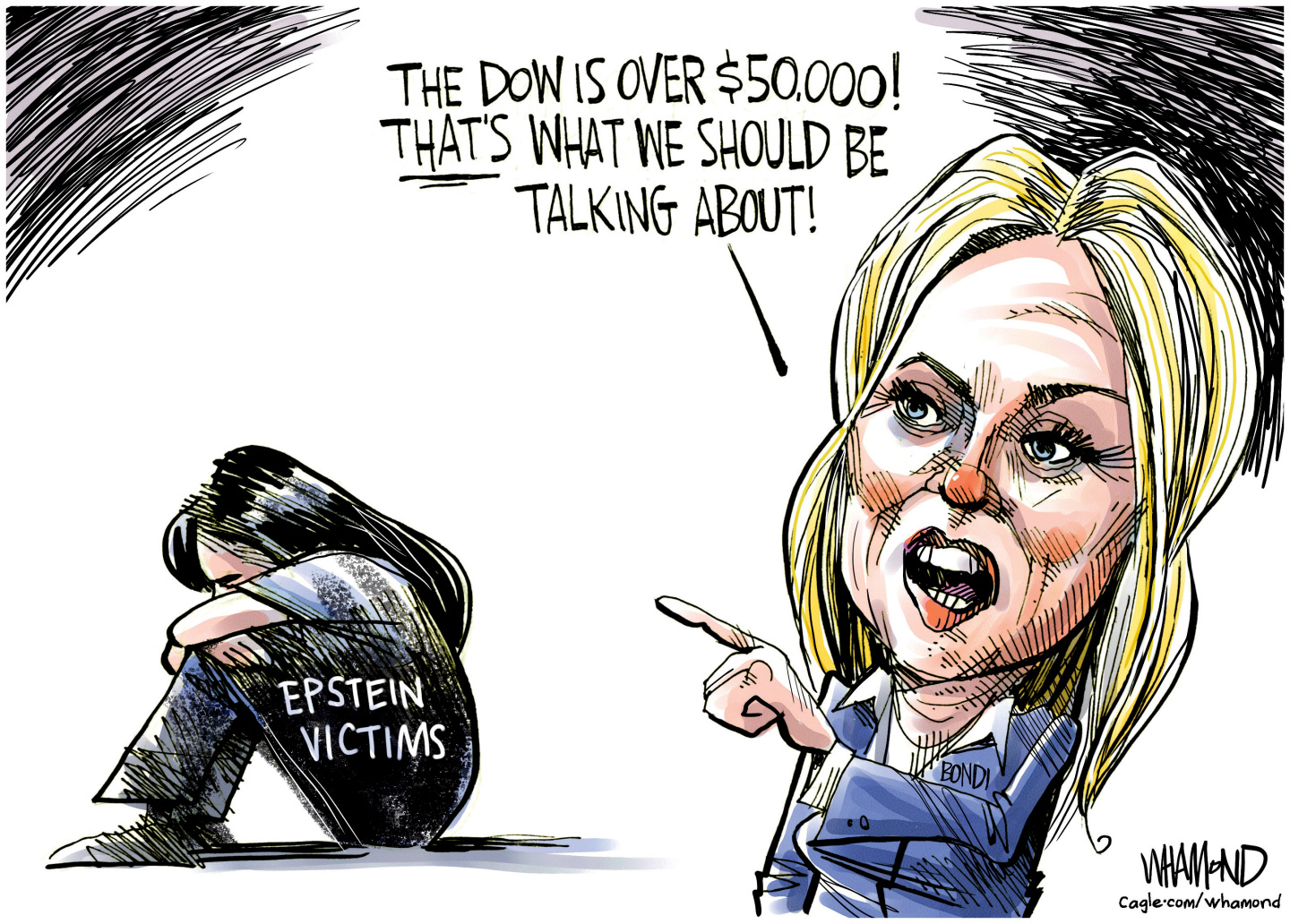

Political cartoons for February 12

Political cartoons for February 12Cartoons Thursday's political cartoons include a Pam Bondi performance, Ghislaine Maxwell on tour, and ICE detention facilities

-

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ return

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ returnThe Week Recommends Carrie Cracknell’s revival at the Old Vic ‘grips like a thriller’