Paul Manafort, the gentleman thief

This is what happens when you stop enforcing the law on rich people

One of the most striking things about the indictment of President Trump's former campaign chairman Paul Manafort and adviser Rick Gates — and the guilty plea from another Trump campaign adviser George Papadopoulos for lying to the FBI — is the brazenness and incompetence of it all. Manafort and Gates allegedly barely even tried to hide their ill-gotten gains, while Papadopoulos communicated through a hilariously insecure channel (namely, Facebook chat).

It's emblematic of the culture of impunity that has developed in the American elite over the last generation. Rich people like Manafort and Trump have learned that they can get away with just about anything. Why even bother trying to hide things, if nobody will even try to catch you?

If nothing else, perhaps the investigation of Special Counsel Robert Mueller will put some long-overdue fear into the huge population of upper-class American criminals.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Now, it's important to note that while Papadopoulos pleaded guilty, Manafort and Gates pleaded not guilty, and have not been convicted of anything yet. Like any other accused criminal, they deserve their day in court (or perhaps their chance to plead guilty and roll on other criminals further up the food chain in exchange for a reduced charge).

However, the alleged money laundering conducted by Manafort was so obvious that a couple attorneys spotted it months before the indictment landed. The alleged scam, as detailed in the indictment, worked like this: First you create a company in some foreign tax haven (in this case Cyprus, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and the Seychelles), and buy some property with that company. Then, take out a loan against the property and claim it's for home improvements. Hey presto, you've got a bunch of money, and you don't have to claim it on your taxes or say where you got it. It's a super-common way to launder money.

But it can also be a fairly easy crime to root out, because you're obviously not spending the money on home improvements. Two lawyers in New York, Julian Russo and Matthew Termine, discovered Manafort's transactions through public records, and published them on their own site back in February. The transactions looked extremely suspect. The Intercept's David Dayen did some digging of his own, and confirmed the story. Among other odd things, on a couple of Manafort's properties he had borrowed far more than the property was worth — and he reportedly spent the money on a slew of obvious and extremely expensive luxury goods. If you wanted to get caught laundering money, that's pretty much exactly how you'd go about it.

Or consider another of Manafort's alleged crimes: failing to register as a foreign agent. The Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938 requires lobbyists for foreign governments to register as such. In elite Washington circles — where roughly every fourth person is taking money to downplay human rights abuses conducted by Kazakhstan, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, or similar countries — violating this law is absolutely rampant, because the Justice Department has barely enforced it for decades. Trump's former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn, who is reportedly another target of the Mueller probe, also may have violated this law, when he lobbied on behalf of Turkish interests and only afterwards registered as a foreign agent (just as Manafort did).

Indeed, Manafort's indictment created a wave of unease among the well-heeled dictator shills of both parties in Washington. "It’s a swampy place, and the swampy stink knows no partisan allegiance," a senior Democratic congressional aide told Buzzfeed News' John Hudson and Zoe Tillman. A broad crackdown is probably unlikely — but there have already been some bipartisan career casualties. Tony Podesta, founder of the Podesta Group and brother of Hillary Clinton's campaign chair John Podesta, stepped down from his firm on Monday because he had lobbied on behalf of the same Ukrainian interests as Manafort and is now under investigation by Mueller as well.

Papadopoulos, by contrast, appears merely real stupid. The unsealed indictment (which he admitted as fact as part of the plea deal) says that after lying to the FBI about trying to arrange contacts with Russian sources through a professor at the London Academy of Diplomacy, and the director of programs at the Russian International Affairs Council, Papadopoulos deactivated his Facebook account (which had chats with Timofeev) and got a new phone number. The FBI, of course, had no problem obtaining the chats, and Papadopoulos was arrested on July 27. What a complete chump.

As Jesse Eisinger writes, punishment for crime committed by elites has all but collapsed over the past couple decades. Whether it's allegedly paying the district attorney not to prosecute a sexual assault charge or the rise of deferred prosecution agreements for white-collar crime, elites have lately gotten away with a staggering amount of lawbreaking.

This is the result: an absolute plague of dimwitted swindlers, liars, and two-bit cheats in the highest circles of government.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

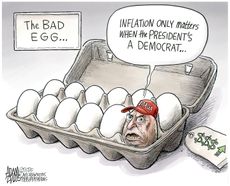

Today's political cartoons - February 1, 2025

Today's political cartoons - February 1, 2025Cartoons Saturday's cartoons - broken eggs, contagious lies, and more

By The Week US Published

-

5 humorously unhealthy cartoons about RFK Jr.

5 humorously unhealthy cartoons about RFK Jr.Cartoons Artists take on medical innovation, disease spreading, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Brodet (fish stew) recipe

Brodet (fish stew) recipeThe Week Recommends This hearty dish is best accompanied by a bowl of polenta

By The Week UK Published

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published

-

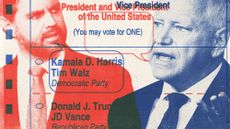

US election: who the billionaires are backing

US election: who the billionaires are backingThe Explainer More have endorsed Kamala Harris than Donald Trump, but among the 'ultra-rich' the split is more even

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

The life and times of Kamala Harris

The life and times of Kamala HarrisThe Explainer The vice-president is narrowly leading the race to become the next US president. How did she get to where she is now?

By The Week UK Published

-

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?Today's Big Question 'Diametrically opposed' candidates showed 'a lot of commonality' on some issues, but offered competing visions for America's future and democracy

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

1 of 6 'Trump Train' drivers liable in Biden bus blockade

1 of 6 'Trump Train' drivers liable in Biden bus blockadeSpeed Read Only one of the accused was found liable in the case concerning the deliberate slowing of a 2020 Biden campaign bus

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

How could J.D. Vance impact the special relationship?

How could J.D. Vance impact the special relationship?Today's Big Question Trump's hawkish pick for VP said UK is the first 'truly Islamist country' with a nuclear weapon

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published