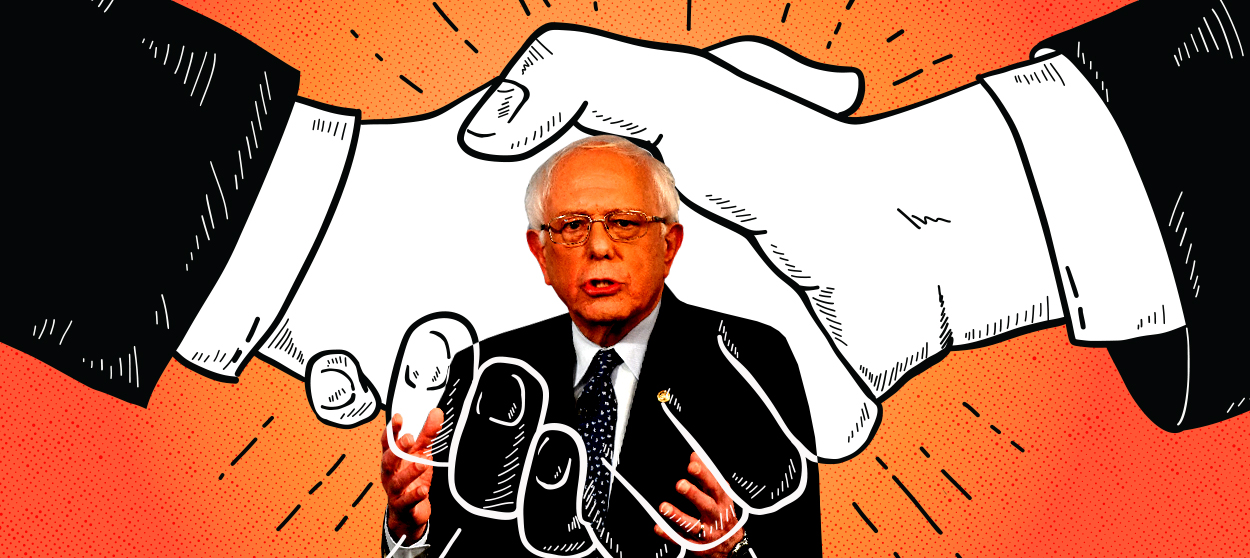

Bernie Sanders has conquered the Democratic Party

His best ideas are rapidly becoming party orthodoxy

Bernie Sanders' bid for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2016 was not universally welcomed, to put it mildly. His basic argument was that Democrats could assemble a cross-ethnic and cross-class coalition by offering big universal public programs like Medicare-for-all and free college tuition. But large portions of the party dismissed him as an interloper, a naive radical, or even just another entitled white male.

Which makes developments since the 2016 election rather interesting: Quietly but steadily, the Democratic Party is admitting that Sanders was right.

Let's begin with the signature issue of Sanders' campaign: a national single-payer health-care program, or Medicare-for-all as it's known.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Hillary Clinton, who ultimately bested Sanders for the party's nomination, insisted the idea "will never, ever come to pass." Fast forward roughly a year, and Sanders' proposed Medicare-for-all legislation attracted 16 Democratic co-sponsors, including likely presidential contenders Sens. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), Corey Booker (D-N.J.), Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.), and Kamala Harris (D-Calif.).

Meanwhile, the liberal think tank Center for American Progress has proposed bundling Medicare, Medicaid, and CHIP into a public health coverage option on steroids. It would use bargaining tactics similar to Medicare to hold down health-care costs; premiums and cost-sharing would be capped to make it affordable for low-income Americans; and children and new retirees would be enrolled in it automatically. This isn't the same as Sanders' proposal, which would involve no premiums or cost-sharing at all (a provision unlikely to survive), and would blow up the whole health-care system in one fell swoop. But the idea is clearly for the new public option to ultimately swallow the rest of the system.

To the extent the CAP proposal disagrees with Sanders, it's over theories of change rather than the end goal. Furthermore, CAP is closely aligned with the centrist Clinton wing of the Democratic Party, and does a lot of the party's policy construction. That the think tank felt the need to release this proposal shows how profoundly the ground has shifted in a short time.

Then there's the minimum wage. During the 2016 campaign, the Democrats were nervously tip-toeing up to $12 an hour as the new national minimum they wanted. But Sanders' surprisingly strong bid for the nomination had its effect, forcing a $15-an-hour minimum onto the party platform. Since then, it's been the Democratic default: The bulk of the party in the Senate has consolidated around a $15-minimum legislation.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Meanwhile, a Democratic bill to make college tuition and living expenses debt-free has eight senators and 14 House members co-sponsoring.

In fact, parts of the Democratic Party are arguably trying to out-Sanders Sanders.

The social democrat from Vermont never got around to endorsing a universal child allowance, for instance. But the idea clearly comports with his overall philosophy and preference for Nordic-style welfare states. Enter Sens. Michael Bennet (D-Colo.) and Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio), who have a bill that would transform the currently-inadequate child tax credit into the closest possible thing to a universal child allowance, while still being run through the tax code.

But the most interesting policy here is a federal job guarantee. This would be a public option for work, offering employment with a living wage and benefits to anyone who wants it. The idea goes back at least as far as the Civil Rights movement. Stephanie Kelton, one of Sanders' key economic advisers, has been working on the idea for years with economists associated with the University of Kansas City-Missouri and the Levy Institute, and pushing it up through Sanders' network of political outfits. Meanwhile, another group of economists, including Mark Paul, William Darity and Darrick Hamilton, has also been building out the idea. And Sanders himself organized a townhall with Hamilton to talk about it.

CAP suggested a watered-down but still admirable version of a job guarantee a few months ago. Then Gillibrand publicly endorsed a job guarantee in mid-March. And she's kept up the drumbeat since. This past Friday, Booker released legislation for a pilot program version of the job guarantee, built off Paul, Darity and Hamilton's work. Then on Monday, Sanders pushed his chips in, announcing legislation for a full-bore national version of the policy.

This actually looks somewhat similar to how Clinton, Barack Obama, and John Edwards all egged each other on towards health reform in the 2008 campaign. Parts of the Democratic Party are now taking the basic building blocks of Sanders' political philosophy and running with them.

"Donald Trump's victory implies that people need to be more bold," Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.) recently observed. "People yawned at the smallness of American politics, at the stagnation of American politics, at the same faces, the same ideas, the same talking points." In the late stages of Obama's presidency, before Trump won, the idea of the Democrats hitching their wagon to Medicare-for-all, a $15 minimum wage, or a national public works program seemed radical. But if Sanders' campaign delivered no other message to the Democrats, it was that they needed to get out of their comfort zone. Go big or go home.

The Democrats went home in 2016. So now they're finally going big.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: which party are the billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: which party are the billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration

-

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event