The big lie at the heart of the technology revolution

The world needs gatekeepers

There is a fundamental lie at the heart of the techno-populist-utopian vision that dominates so much of 21st century Western culture.

The lie is the notion that the world would be a better place without gatekeepers. If only the most powerful information-dissemination technologies ever devised were left open to all — unregulated, uncontrolled, ungoverned by authorities who make decisions about what's acceptable and what isn't — the world would be a much more free and thriving place, the thinking goes. But for this to be true, human beings (individually but perhaps especially collectively) would need to be far more capable of exercising wise judgment than they manifestly are.

The truth is that the world needs gatekeepers.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

That can be difficult for individualistic, egalitarian citizens of liberal democracies to accept. We have long been taught to revere the marketplace of ideas. Let a million ideas bloom, and through competition with each other, the best will thrive and spread while the worst die out under scrutiny.

But this is not what happens in our shared digital lives. Just consider the case of Alex Jones and InfoWars.

Jones' paranoid, rage-fueled conspiracy-mongering has a large and devoted audience. His brand of maliciously false civic poison thrived when left unchecked by gatekeepers. It took Apple, Google, Facebook, Spotify, and Co. stepping in and finally banning InfoWars to stop the spread of this toxin.

This is not an example of censorship. Governments censor. Businesses make decisions about how to conduct business. The Washington Post or The New Yorker aren't engaging in censorship when they make editorial decisions about what and whom to publish. They are acting as gatekeepers controlling which authors and ideas get to appear under their name and with their imprimatur. Their (physical or digital) pages aren't public property.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

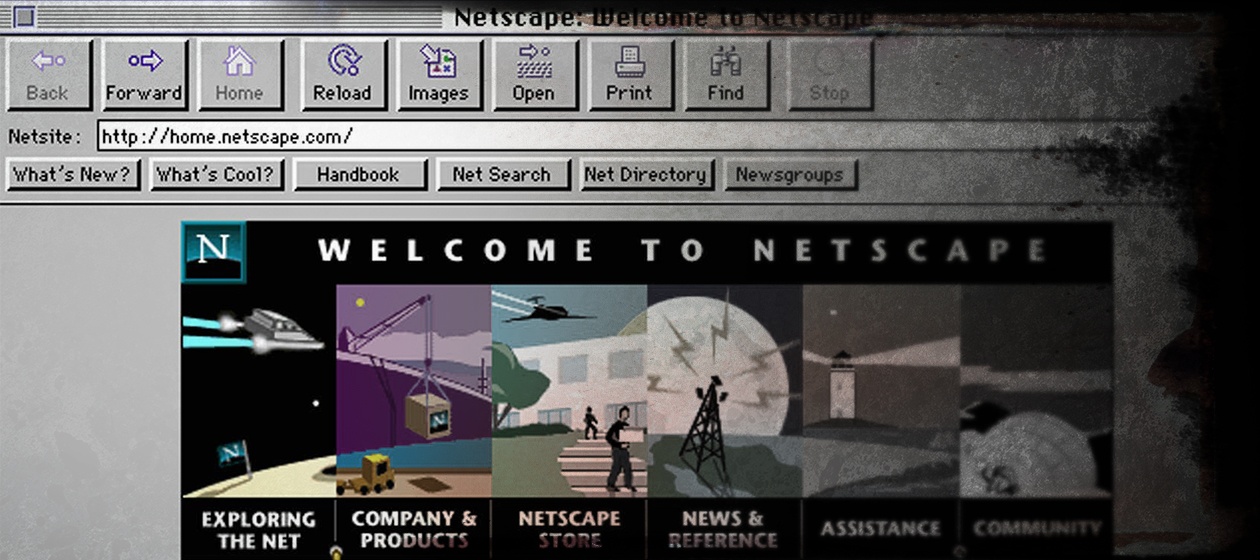

Now, many people like to think of social media platforms as sort of like public property — giant billboards in a worldwide common room to which everyone has open access to post anything they want. They believe the whole point of social media is leaving behind the era of gatekeepers in favor of a digital democracy of ideas that welcomes everyone equally.

But there are actually clearly gatekeepers on social media and the mainstream internet, and long have been. If you doubt it, try posting hardcore porn on YouTube. Or uploading a podcast championing child abuse to Apple or Spotify. Or announcing an intent to engage in mass murder on Facebook. There are clear (if fairly minimal) limits and community standards on all of these platforms.

What we're seeing now is an acknowledgement from these digital giants that there need to be more of them.

This is a good thing — even if we doubt the capacity of these companies to make such judgments with perfect wisdom and fairness. Acknowledging the need for limits and standards pushes back against one of the premier delusions of our moment: that the world will be improved if the internet is left uncontrolled by any authority whatsoever.

The achievement of most good things — including moral decency, thoughtfulness, civility, knowledge, and wisdom — depend on the existence of gatekeepers imposing and upholding exacting standards. The sooner we come to recognize this reality and act on it, the better.

The reason why the marketplace of ideas often fails to function as it's supposed to is that it's based on a false (or at least overly simplified) notion of human nature and society, presuming that people are roughly equal in their cognitive and emotional capacities, and that the surrounding culture will automatically inculcate norms and habits that facilitate the acquisition of knowledge and the capacity to judge wisely.

But what if both assumptions are false? What if some people are capable of the careful, methodical weighing of evidence but others are not? What if some find it possible to live with the doubt and exigency that accompanies a life of thoughtfulness, while others gravitate out of fear and the craving for certainty to the easy answers and facile simplifications offered by charlatans and demagogues who traffic in absurdly implausible conspiracy theories?

What if human beings are not intellectually equal?

In such a circumstance, the marketplace of ideas will begin to break down — and more fully the more free and open the market becomes, as technology provides a megaphone and a seemingly infinite audience to every would-be huckster on the planet.

President Trump's political career was launched by a racist conspiracy theory, his campaign fueled in part by support from InfoWars, his victory partly a function of the dissemination of disinformation by foreign powers out to subvert American liberal democracy. This is what happens when the dream of a marketplace of ideas has been supplanted by the nightmarish reality of a world in epistemological collapse. In such a world — our world — the loudest, most viscerally satisfying "take" often gets far more traction than the smartest one, precisely because we've lost the capacity to reach any kind of consensus about what even counts as "smart."

So yes, we could use a few more online gatekeepers — even if they do a merely mediocre job, and even if their judgments, at least at first, seem to lack consistency and legitimacy.

Knocking down authorities is always easier than setting them up. But that doesn't mean we don't need them at all.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook