The business media's nauseating nostalgia for the financial crisis

What crazy adventures we had when we were young and the world economy was about to collapse!

The 10th anniversary of the financial crisis has arrived with the predictable, month-long blizzard of retrospectives and commemorations in the business media. These segments have dutifully checked off all the main issues financial journalists imagine the public expects them to cover: the run-up to the crisis, the transition from the collapse of Lehman Brothers to the passage of TARP, low interest rates and their enduring impact on the global economy, the crisis' political legacy, whether we're any safer today, and so on. There's been a plodding aspect to much of this coverage, but fortunately the doyens of financial news have not left viewers to starve on a grim diet of discussions about the rehypothecation of collateral. With the boring stuff out of the way, the financial media has knuckled down to the real business of this 10-year anniversary extravaganza: the reunion tour.

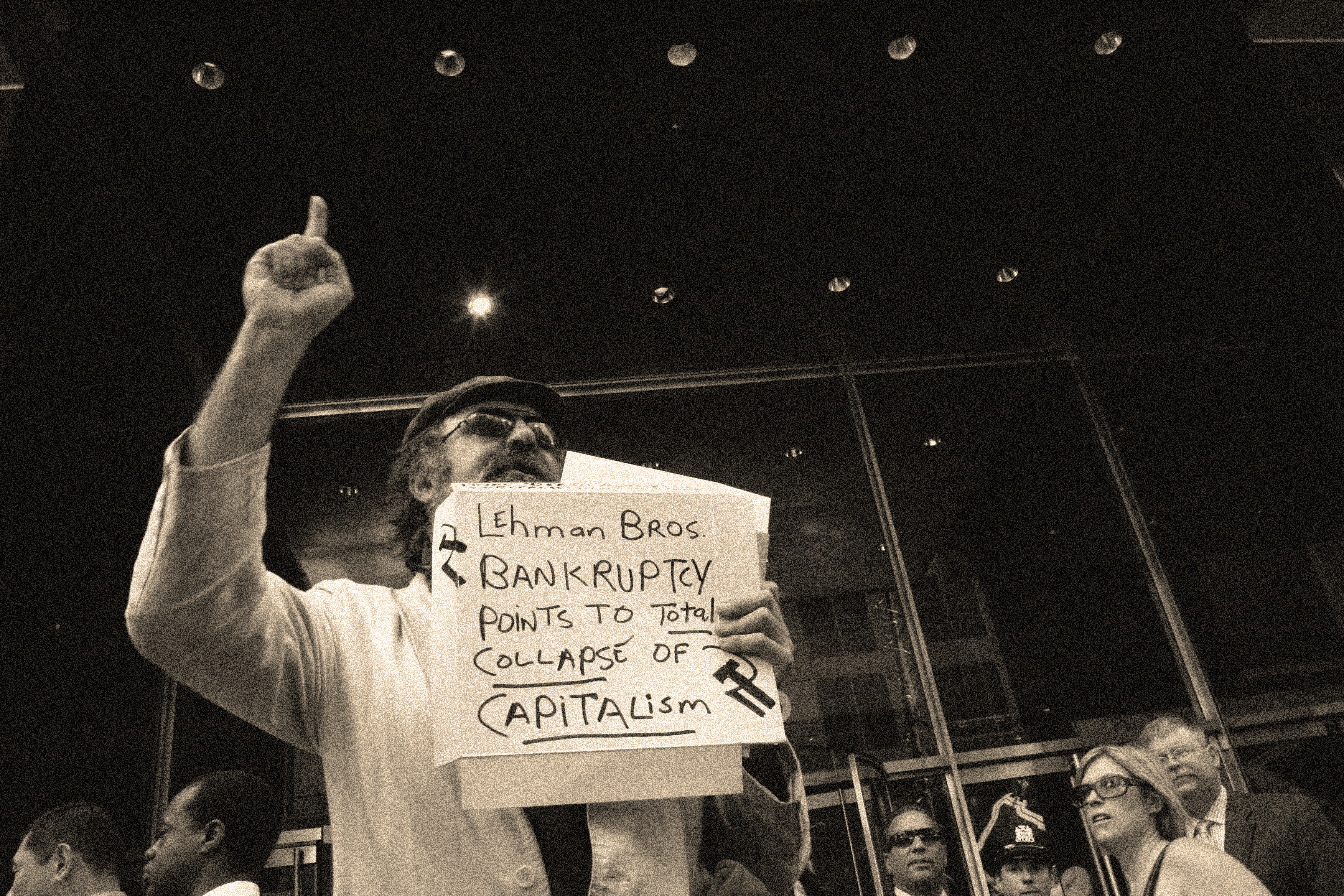

This nauseating display was most conspicuous around the anniversary of Lehman Brothers' bankruptcy earlier this month. That weekend, CNBC, Bloomberg, Fox Business, and the big press outlets ran extensive interviews with all the major players of the crisis. Each one boiled down to the same question: Where were you when Lehman went down? Hence we learned that JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon was having dinner with his soon-to-be-son-in-law's parents when the news of Lehman's imminent collapse came through. Warren Buffett was at a charity concert in Canada, setting the scene for a hilarious mix-up with a fax machine that ended with him not buying Lehman Brothers. Bob Diamond was struggling to master voicemail. Reporters over at The New York Times recalled the dinners of Lehman weekend: steak at Bobby Van's on 50th Street for Eric Dash, pizza for Andrew Ross Sorkin. On and on it went. Even the Bank of England got in on the act, pushing out a quick vid featuring the Lehman weekend stories of a bunch of nameless staffers ("I was cycling with my family in Richmond Park," "I was actually on a canal boat in Essex") that did impressively bad traffic on YouTube. With the help of the media, players big and small have all had their chance to help recast the gravest economic slump of our time into a gentle comedy of manners involving canceled dinner plans and a handful of mild technological misunderstandings.

The financial crisis slashed the value of America's publicly traded companies, put a crater through household wealth, worsened an already-appalling racial wealth gap, sent wages for the bottom 70 percent of American workers plummeting, and fed, even through the years of superficial recovery that followed, the resentment and economic insecurity that allowed a figure like President Trump to prosper. But let's not lose sight of the bigger picture: It was also great fun. It was exciting. Indeed for many of the main actors — the guys and (rarely) girls at the center of the action, pushing the buttons of stimulus and making fiat money rain — it was the best weekend of their lives. A weekend from which, of course, these actors emerged as heroes. Thankfully, the financial media's commitment to Lehman weekend trivia has allowed us not to lose sight of this happy tableau. Risk and leverage and derivatives and all that stuff: Who cares about that? The real question the world needs the answer to is: What was Jamie Dimon wearing the exact moment when Barclays killed its deal to buy Lehman?

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The 10th anniversary festivities reached a peak of nostalgification when Sorkin took to the stage at the Brookings Institution to interview Ben Bernanke, Tim Geithner, and Hank Paulson about their experience of crisis month. The band, literally, was back together, and with Sorkin's giddy prompting, the memories flowed like lender-of-last-resort liquidity. During his time in public office Geithner had a reputation for being slightly crotchety, slightly impatient — a precious egghead with too-high hair — but on stage at the Brookings Institution, free to jam with Hank and Benny, his hair long having descended from the Krameresque heights it reached during the crisis, he was positively loose, man. He was funky. Paulson rambled and contradicted himself in that inimitable way that only he and Grampa Simpson can, and as for Bernanke? Well, he was the same as always: wise old Ben, the prof with the trim beard and encyclopedic knowledge of the history of counter-cyclical stimulus who could now afford to look back on the whole crisis thingy with a fond, Gandalf-like chuckle.

If the band members were relaxed, it's because Sorkin did them the favor of keeping the focus of his questions squarely on the small moments. The crowd loved it. Paulson said he had trouble sleeping some nights in September 2008. A ripple of laughter went around the room. Bernanke described a meeting with then-Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid. More laughs. Geithner said the hardest thing about the crisis was sitting across from his wife in the morning. Sniggers. "Just seeing the look on her face," he said. Laughs. "Just that mixture of despair and doubt, like, she looked at what we did and said, 'Really?'" The biggest laughs of all. What crazy adventures we all had when we were young and the world economy was about to collapse! Later in the gig Geithner bemoaned the depth of public anger that accompanied the $700 billion bailout of the financial system — a reaction he attributed to bad PR, a failure to better communicate the reasons behind the bailout. If only the optics had been better, he mused, yucking it up on stage with his famous pals for a room full of rich people.

Nostalgia, Christopher Lasch once said, is the abdication of memory. If the media has indulged the financial crisis nostalgia-fest so gleefully over the past few weeks, the desire to forget its own role in abetting the crisis may be part of the reason why. By taking a complex, cumulative, and profound moment of global crisis and turning it into the occasion for a series of jokey reminiscences, the financial media not only disrespects the millions of people who suffered — and continue to suffer — real distress as a result of Wall Street's malpractice, it diverts attention from a more searching examination of the media's own conduct in the run-up to the crisis and how little things have changed in the years since. It's no accident that Sorkin, who's built a career on parroting back to Wall Street's leading lights the things they've just told him, has been the most faithful chronicler of financial crisis trivia. To call him an access journalist would be an offense to the word "journalism;" he's less a reporter than a stenographer. In this, he is more representative than exceptional.

Journalists don't escape diagnosis of the causes of the crisis without blame. They missed all the warning signs of a growing calamity, sacrificed accountability for access, and were complicit in puffing up the financial industry's pre-crisis narrative of innovation and progress — a narrative designed to secure only the lightest fetters of regulation. If the past month shows us anything, it's that the the financial media's relationship with the industry it ostensibly covers hasn't changed one bit. In The New York Times' recent piece about its own reporters' experience of Lehman weekend, business editor Lawrence Ingrassia recalled a July 2008 meeting with Paulson in which the then-treasury secretary was "quite unconvincing." But the story about Paulson the Times published following that meeting said nothing of the sort: On the contrary, it was a fairly positive, soft-focus profile. This is an omission that feels, in retrospect, emblematic. Everything about the media's desire to trivialize the crisis these past few weeks and hero-worship the bank CEOs and officials who steered the response speaks to this enduring reality: Most financial journalists still view Wall Street with a mix of childish awe and deference. For anyone looking to the financial media to provide the scrutiny and accountability needed to head off the next financial crisis, this may be a sign that it's time to give up.

This presupposes, of course, that anyone — journalist or otherwise — has the power to see the next crisis building, which may be a forlorn hope. On stage at the Brookings event, Sorkin asked Paulson whether better data might have improved the quality of officials' decision-making in response to the crisis. "I don't think it was about data," Paulson replied. "My strong belief is that these crises are unpredictable in terms of cause or timing or the severity when they hit." This has been a popular take in recent weeks: The next crisis, we've been told, will be unlike the last one, and just as difficult to plan for.

In other words, there's bad news and good news. The bad news: The Wall Street elite doesn't have a clue how to prevent the next crisis and doesn't think it bears any responsibility to guide the financial system away from the excesses that might feed it. The good news: Ten years after the next crash we'll be able to come together and have a reunion tour with a whole new set of actors and mediocre anecdotes.

Oh next financial crisis, the memories you'll give us!

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Aaron Timms is a Brooklyn-based writer. His writing has appeared in The Guardian, The Outline, The Daily Beast, and The Los Angeles Review of Books.

-

Colleges are canceling affinity graduations amid DEI attacks but students are pressing on

Colleges are canceling affinity graduations amid DEI attacks but students are pressing onIn the Spotlight The commencement at Harvard University was in the news, but other colleges are also taking action

-

When did computer passwords become a thing?

When did computer passwords become a thing?The Explainer People have been racking their brains for good codes for longer than you might think

-

What to know before 'buying the dip'

What to know before 'buying the dip'the explainer Purchasing a stock once it has fallen in value can pay off — or cost you big

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are the billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are the billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration

-

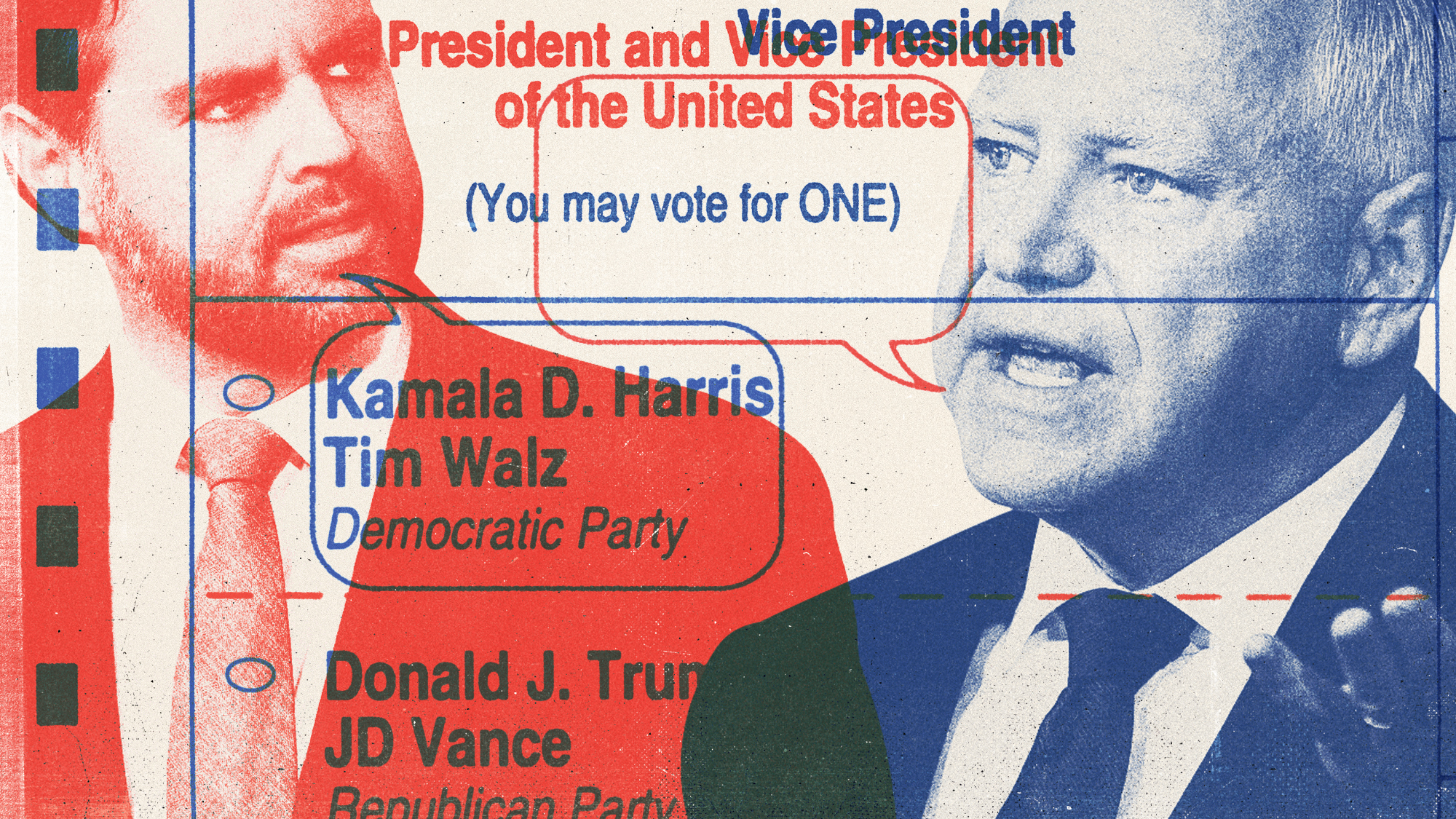

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event

-

The life and times of Kamala Harris

The life and times of Kamala HarrisThe Explainer The vice-president is narrowly leading the race to become the next US president. How did she get to where she is now?

-

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?

Will 'weirdly civil' VP debate move dial in US election?Today's Big Question 'Diametrically opposed' candidates showed 'a lot of commonality' on some issues, but offered competing visions for America's future and democracy