The delusion of certainty in the Kavanaugh debate

Liberals are sure he's guilty. Conservatives are sure he's innocent. How about some humility and restraint, please?

If there's one thing every conservative Republican knows, it's that Brett Kavanaugh is a devoted husband, loving father, and brilliant jurist who's always treated women with respect and who is now the innocent victim of a smear campaign orchestrated by the left and its amen chorus in the liberal media.

And if there's one thing that every progressive Democrat knows, it's that Brett Kavanaugh is a liar and a fraud whose jurisprudence and personal behavior toward women going all the way back to high school consistently displays a flagrantly misogynist contempt for female autonomy and dignity.

Of course, neither side truly knows any such thing. Each side believes it on the basis of partial evidence and reasoning that's highly motivated by prior ideological commitments.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

That doesn't mean it's impossible to reach a fair-minded judgment about the charges and counter-charges swirling around the Supreme Court nominee. But it does mean that fair-minded observers of the circus should be staking out their positions with far more humility and tentativeness than they are. That is, of course, if they care more about reaching the truth than contributing to the advancement of a scorched-earth partisan crusade.

Knowledge is a tricky thing. I know the sky is blue because I've seen it with my own eyes thousands of times. But how do I know that the Earth revolves around the sun rather than the other way around? I have no experience of this. On the contrary, my senses tell me otherwise. I see the sun rise, move across the sky, and set every day, while the ground under my feet feels perfectly stationary. Yet I will readily say that I know the Earth revolves around the sun.

It is more accurate to say that I believe the Earth revolves around the sun because I trust the scientists who tell me that when it comes to the truth about the natural world, my senses are unreliable. Of course it's also possible that I can learn how to make the precise observations and do the mathematical calculations that will verify the belief for myself, allowing me to understand how scientists originally came to this conclusion. In that case, it would be possible to say with accuracy that I know the Earth revolves around the sun.

But in plenty of other matters, such verification isn't possible. It's unlikely I can or will personally replicate the work of evolutionary biologists sufficient to demonstrate that Darwin was right about the process of natural selection or that climate scientists are right about the anthropogenic causes of climate change. It's not likely at all that I would be able to verify for myself that the universe began with the Big Bang or that it's impossible to travel faster than the speed of light, let alone the far more fanciful nuances of quantum mechanics or string theory. I don't possess knowledge of these subjects. I believe certain things about them because I trust the people who do possess knowledge of these subjects.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Now let's think about what may have happened at a Maryland house party in the summer of 1982. Did a 17-year-old Brett Kavanaugh and a 15-year-old Christine Blasey Ford attend such a party? Did Kavanaugh assault Ford there? Kavanaugh denies it categorically. His defenders point out that no one else has verified the story, and that the accused should be granted a presumption of innocence.

Ford's defenders counter that this is not a trial but rather an extremely high-stakes job interview and that the standards that prevail in criminal proceedings shouldn't apply. And regardless, men accused of sexual harassment and assault, up to and including rape, have for too long been granted the benefit of the doubt, while the claims of their accusers have too often and too easily been dismissed. It's long past time to start righting this unjust imbalance.

As general statements about the presumption of innocence and guilt, both sides have a point. As the slew of verified accusations of sexual misconduct against powerful, prominent men over the past year makes abundantly clear, lots of men have too often received a pass, with those who accuse them forced to carry a greater burden of proof than is warranted. Yet it also remains true that men are sometimes falsely accused and it's neither reasonable nor fair to assert as a principle that accusers ought to be automatically believed — either in a real court or the court of public opinion. Each accusation needs to be evaluated on its own terms to determine if it has merit.

That leaves us where we are — with Ford's accusation hanging in the air, unverified by anyone else, as we await her testimony and Kavanaugh's response to it before the Senate Judiciary Committee, and another, flimsier claim reported in The New Yorker. (Lawyer Michael Avenatti claims to have evidence of other Kavanaugh misdeeds, but he has yet to offer any proof beyond wildly inflammatory insinuations.)

If you were already inclined to trust Kavanaugh, the evidence against him is weak enough to justify rallying to his side. ("How dare these liberals engage in dirty tricks against this smart, decent family man who's devoted his life to the law!") But if you were already inclined to distrust him, the evidence against him is strong enough to justify feeling vindicated. ("You mean the guy who seems eager to gut women's reproductive rights shows a pattern of misogyny and violence against women? No kidding!")

The truth, though, is that the evidence, so far, justifies neither conclusion. Neither side can claim, so far, to know what did and didn't happen, what Kavannaugh did or didn't do, more than three decades ago. The evidence warrants further investigation. Without such an investigation, the evidence can be combined with prior assumptions about Kavanaugh's character to justify a belief in his guilt or innocence. But this is a mere belief, rooted in the conflicting assumptions of very different ideological communities, not knowledge.

The only responsible thing to do in such a situation — as opposed to the politically expedient thing to do — is either to suspend judgment or render it with suitable humility and skepticism. In my own case, I am tentatively inclined to believe Ford, but I'd greatly prefer to see some independent verification of at least some aspects of her story. Until such confirmation comes to light, I will withhold final judgment. A few of Kavanaugh's defenders appear to be working to adopt an analogous position on the other side.

Suspending final judgment is hard, because it means keeping one's mind open, and showing a willingness to change it, far longer than most people in our highly polarized time are willing to countenance. But it's nonetheless the only honest response to a situation in which none of us really knows anything at all.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

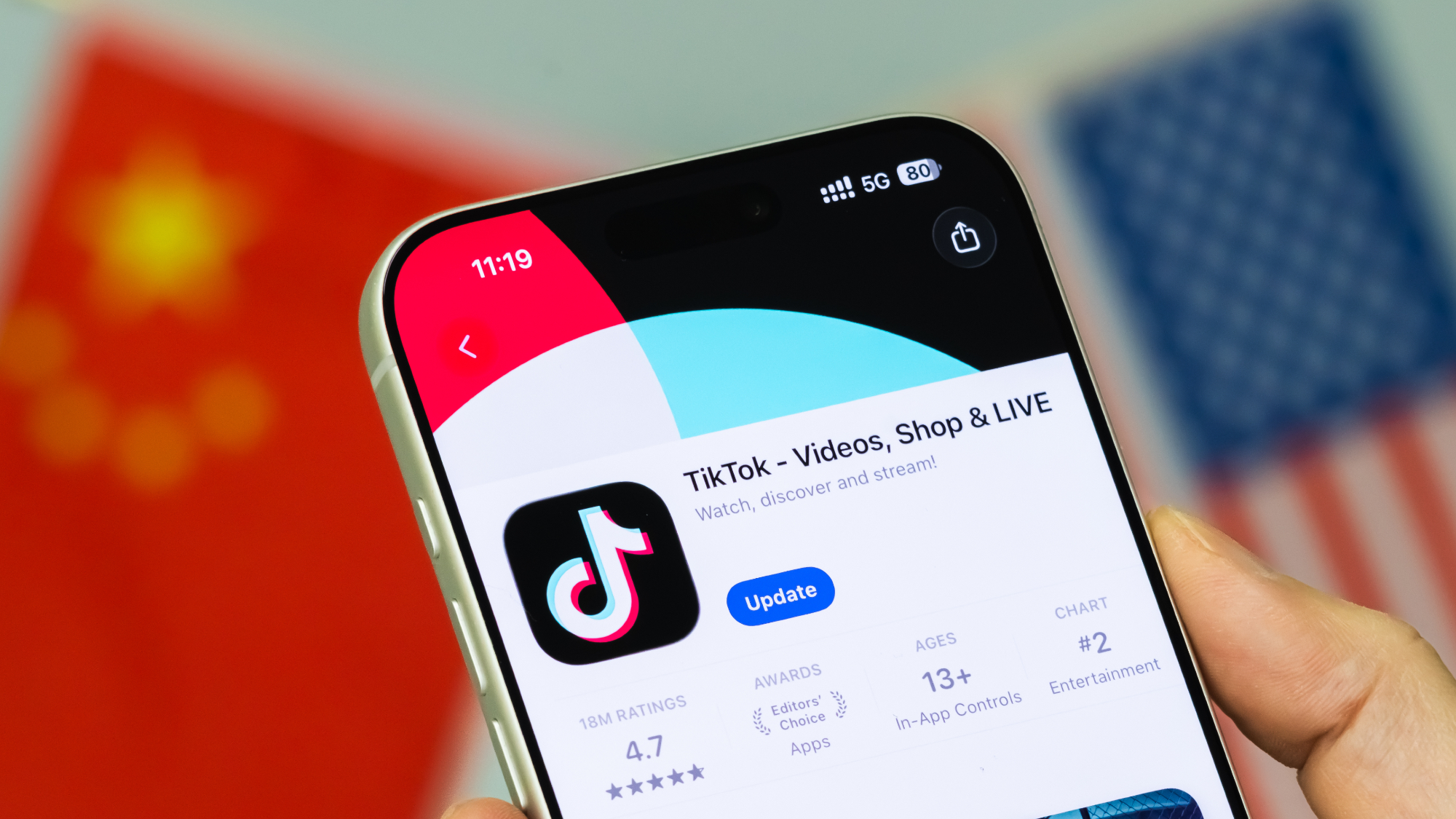

TikTok finalizes deal creating US version

TikTok finalizes deal creating US versionSpeed Read The deal comes after tense back-and-forth negotiations

-

Minnesota roiled by arrests of child, church protesters

Minnesota roiled by arrests of child, church protestersSpeed Read A 5-year-old was among those arrested

-

Learning to ski in the French Alps

Learning to ski in the French AlpsThe Week Recommends Hitting the slopes in my thirties was intimidating but I soon fell in love with the thrilling sport

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred