How did Sars start - and end?

The deadly new coronavirus has been compared with the virus that swept across China in 2003

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

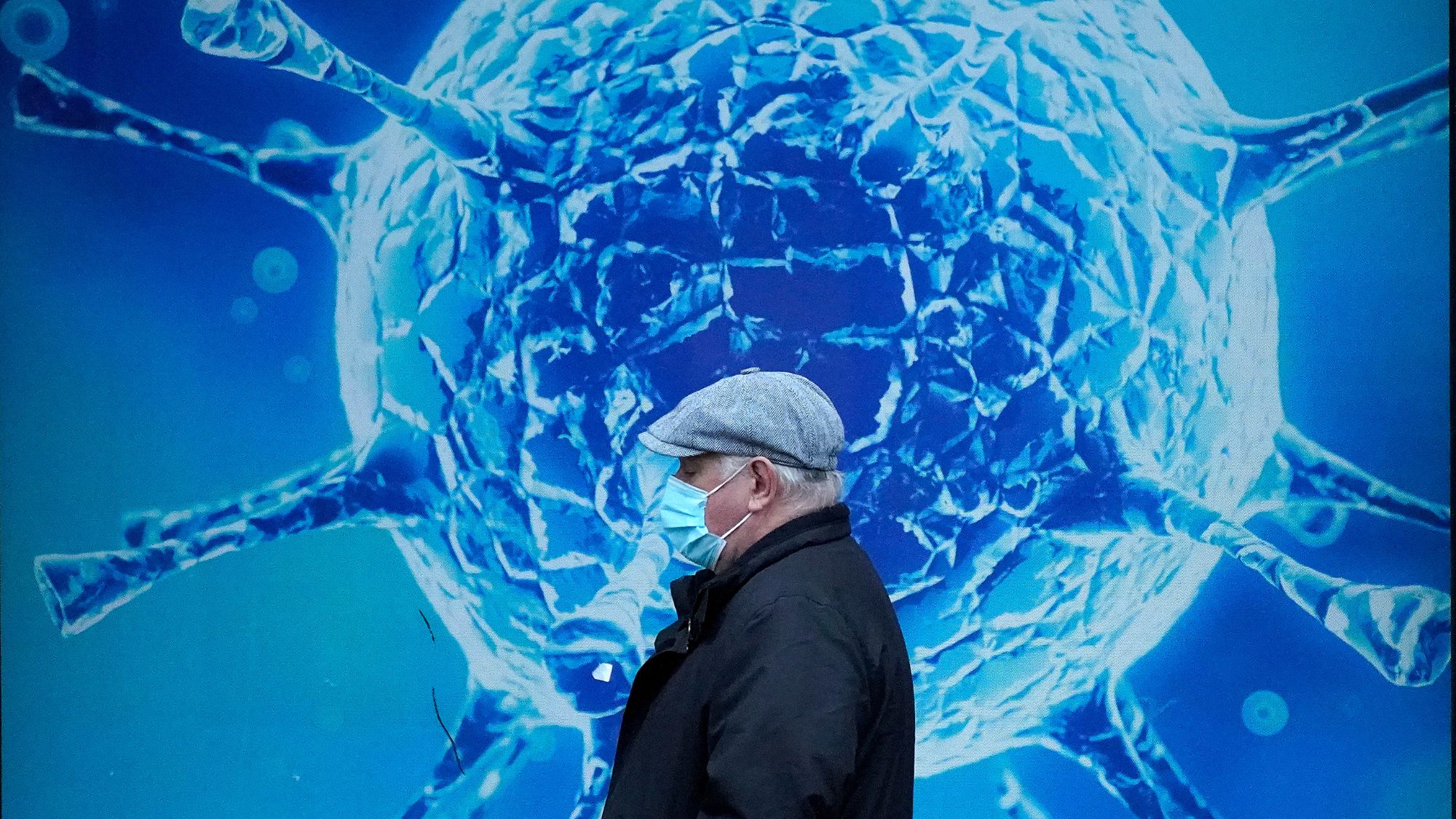

The ongoing coronavirus outbreak, which has reached more than 110,000 cases worldwide, has prompted health experts to look back to past epidemics such as the Sudden Acute Respiratory Syndrome (Sars) infection of 2003.

During the Sars epidemic 17 years ago, 5,327 people on the Chinese mainland were confirmed to have been infected. This figure was overtaken by the new coronavirus outbreak at the end of January and the virus has now spread to 115 countries and territories.

The official name of the new virus - Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (Sars-CoV-2) - was chosen because it is genetically related to the 2003 outbreak (officially Sars-CoV). But the World Health Organization (WHO) has said the diseases have unique characteristics.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How did Sars begin?

The Sars virus originated in China in 2002. The NHS website reports that experts believe a strain “usually only found in small mammals mutated, enabling it to infect humans”.

WHO says Sars is thought to be an animal virus “from an as-yet-uncertain animal reservoir, perhaps bats, that spread to other animals (civet cats) and first infected humans in the Guangdong province of southern China”.

The infection quickly spread to other Asian countries and beyond, with a major outbreak in the Canadian city of Toronto, and a smaller number of cases in other nations, including four in the UK.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Sars affected a total of 26 countries, with 8,098 reported cases and 774 deaths. Those over the age of 65 were particularly at risk.

How did it end?

A raft of measures were taken to contain the outbreak. These included isolating Sars patients and quarantining people who had been exposed to the virus.

“Symbolised by the image of masked faces, Sars struck fear into the public across the globe, triggering drastic measures: mass quarantine in hospital wards enforced by armed guards, infectious passengers hauled off planes, and closed businesses and schools,” according to a WHO news bulletin published in the wake of the 2003 outbreak. “As the epidemic grew, China threatened to execute any Sars patient who violated quarantine.”

Then, after four months of fear, “as quickly as it emerged, Sars vanished,” says HuffPost.

The news site adds: “The virus hasn’t been seen since, leaving people to wonder: Where did Sars go? Was it truly vanquished? And might it ever return?”

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––For a round-up of the most important stories from around the world - and a concise, refreshing and balanced take on the week’s news agenda - try The Week magazine. Start your trial subscription today –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

How do Sars and the new coronavirus compare?

Coronaviruses are a large family of viruses that cause illnesses from the common cold to more severe diseases such as the original Sars outbreak and now Covid-19, explains WHO. A “novel coronavirus” is simply a “new strain that has not been previously identified in humans”, it says.

“Covid-19 differs from Sars in terms of infectious period, transmissibility, clinical severity, and extent of community spread. Even if traditional public health measures are not able to fully contain the outbreak of Covid-19, they will still be effective in reducing peak incidence and global deaths,” according to a report published in The Lancet.

Many more Covid-19 patients have mild symptoms compared with those who had Sars, but this means that they can be easily missed and not isolated, contributing to further spread, says the report.

Last week, WHO said that “globally, about 3.4% of reported Covid-19 cases have died”, although the mortality rate depends on a range of factors, including age and general health. And because many people are experiencing mild symptoms, not all cases are reported, meaning that the rate of deaths per cases might be lower. The UK government says its “very best assessment” is “2% or, likely, lower”.

The first Sars outbreak, on the other hand, resulted in 8,098 reported cases and 774 deaths – meaning the virus killed about 10% of people who were infected.

However, Sars “usually didn’t become contagious until several days after symptoms appeared”, meaning that “actions taken during this period to isolate or quarantine ill patients can effectively interrupt transmission”, reports Bloomberg. But, with the new coronavirus, “it seems that it can transmit quite a bit before symptoms occur”, the site adds.

-

Political cartoons for February 15

Political cartoons for February 15Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include political ventriloquism, Europe in the middle, and more

-

The broken water companies failing England and Wales

The broken water companies failing England and WalesExplainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry

-

A thrilling foodie city in northern Japan

A thrilling foodie city in northern JapanThe Week Recommends The food scene here is ‘unspoilt’ and ‘fun’

-

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the rise

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the riseThe Explainer ‘No evidence’ new variant is more dangerous or that vaccines won’t work against it, say UK health experts

-

Covid-19: what to know about UK's new Juno and Pirola variants

Covid-19: what to know about UK's new Juno and Pirola variantsin depth Rapidly spreading new JN.1 strain is 'yet another reminder that the pandemic is far from over'

-

Vallance diaries: Boris Johnson 'bamboozled' by Covid science

Vallance diaries: Boris Johnson 'bamboozled' by Covid scienceSpeed Read Then PM struggled to get his head around key terms and stats, chief scientific advisor claims

-

Good health news: seven surprising medical discoveries made in 2023

Good health news: seven surprising medical discoveries made in 2023In Depth A fingerprint test for cancer, a menopause patch and the shocking impacts of body odour are just a few of the developments made this year

-

How serious a threat is new Omicron Covid variant XBB.1.5?

How serious a threat is new Omicron Covid variant XBB.1.5?feature The so-called Kraken strain can bind more tightly to ‘the doors the virus uses to enter our cells’

-

Will new ‘bivalent booster’ head off a winter Covid wave?

Will new ‘bivalent booster’ head off a winter Covid wave?Today's Big Question The jab combines the original form of the Covid vaccine with a version tailored for Omicron

-

Can North Korea control a major Covid outbreak?

Can North Korea control a major Covid outbreak?feature Notoriously secretive state ‘on verge of catastrophe’

-

Did Sweden’s Covid-19 experiment pay off in the end?

Did Sweden’s Covid-19 experiment pay off in the end?In Depth Scandinavian country had lower excess death rate than many but immigrants and elderly bore the brunt