When will the coronavirus pandemic end?

Covid-19 may be here to stay

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

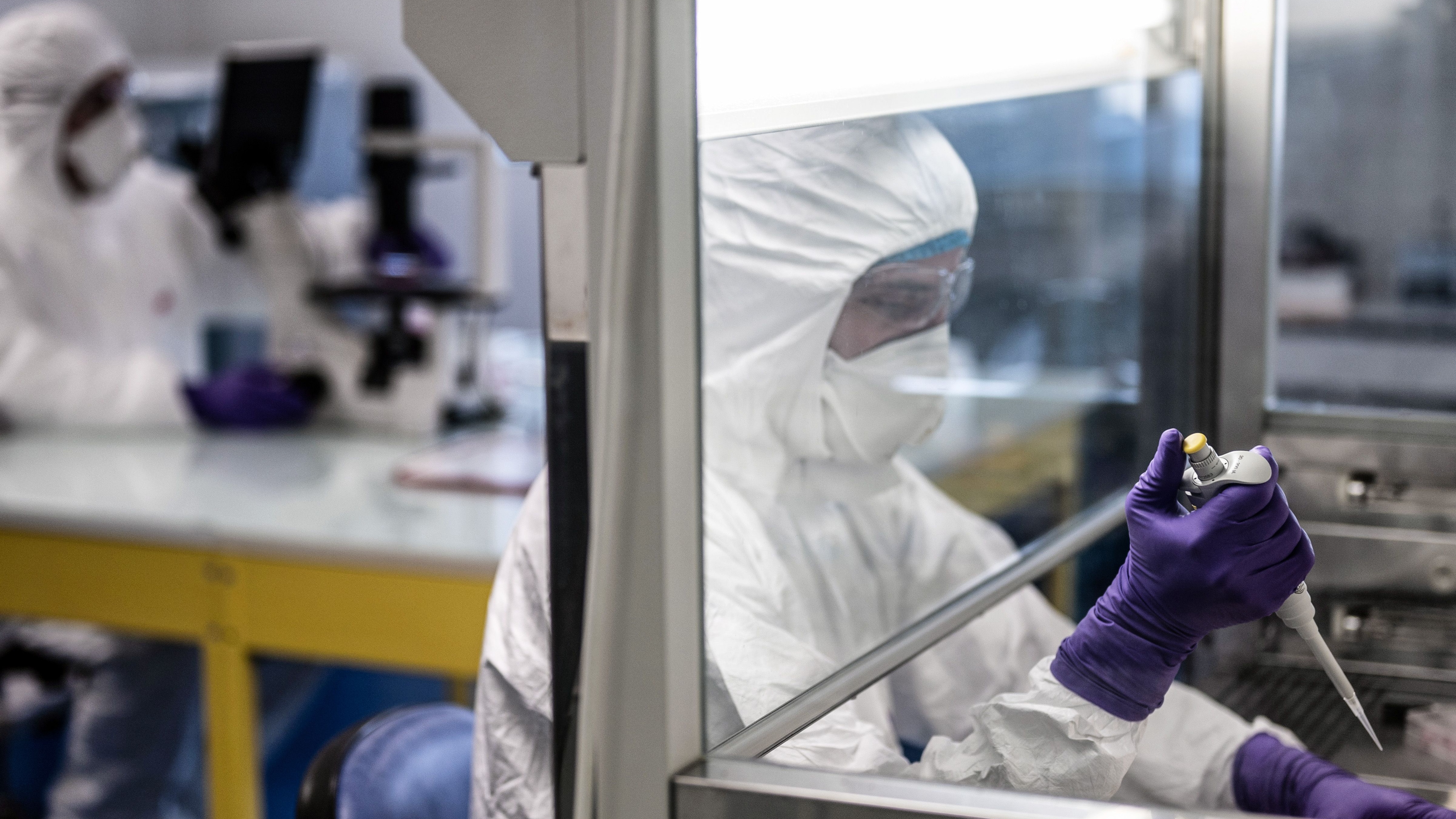

Health officials say they are “frustrated” by a lack of coronavirus testing for NHS workers, which could hamper efforts to bring the pandemic under control.

It was revealed yesterday that just 2,000 of half a million frontline NHS workers had been tested.

Professor Paul Cosford of Public Health England (PHE) said “everybody involved” is unhappy that testing had not “got to the position yet that we need to get to”.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Testing may be one of the most effective ways of ending the pandemic, because it will allow for NHS staff to return to work and battle the virus.

Antibody testing - another form of test, which the government hopes to introduce in the near future - can identify if someone has had the virus and is now resistant.

Resistant people likely would not spread the virus or become reinfected with it, so could restart normal life.

So what else do we know about when and how it could all end?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The outbreak could simply peter out

It is theoretically possible that the new strain of coronavirus might mutate into a less infectious version of itself, and the problem might just go away of its own accord, says Live Science. This is essentially what happened to the Sars outbreak of 2002.

Back then, a virus arose in China and spread to 26 countries around the world before it randomly mutated into something with more severe impact on human health – but which was much less infectious.

We will become immune

It is also possible that the spread of the virus might be limited once people acquire immunity, through vaccination or from having the infection, says Live Science. This is thought to be what eventually happened during the Spanish flu outbreak of 1918.

By that stage, however, the outbreak had killed many millions – and a vaccination for the new coronavirus is not yet ready.

An uncomfortable answer: coronavirus is here to stay

The “most uncomfortable answer”, says Vox, is that the Covid-19 virus will never go away. It could become endemic in the human population, like the common cold.

In this scenario, the virus becomes a “fact of life”, says The Washington Post, pointing to what happened in 2009 with the H1N1 outbreak, also known as swine flu. That virus spread quickly, eventually being contracted by 11% to 21% of the population, says the newspaper.

In most people, H1N1 turned out to cause little more than runny noses and coughs. The original estimates of what percentage of people it might kill turned out to be far too high: the death rate was just 0.01 to 0.03%.

“It is impossible to put a date” on when the virus might go, Dr Simon Clarke, professor of cellular microbiology at the University of Reading told The Independent. “If anyone tells you a date they are staring into a crystal ball. The reality is that it will be with us forever because it has spread now.”

Vaccination will be ‘crucial’

If the new coronavirus does spread throughout the human population, says the Washington Post, “it will be crucial to develop a vaccine”. After the H1N1 outbreak in 2009, a vaccine was developed that was then added to flu inoculations to protect vulnerable people, particularly the elderly.

Earlier this month, professor Neil Ferguson, the chief epidemiologist advising the government, said: “The only exit strategy from this long term is vaccination or some other kind of innovative technology.”

But the World Health Organization (WHO) and many infectious disease experts have predicted that vaccines could be more than a year away, and even then would be reserved for frontline health workers and the most vulnerable first.

Annelies Wilder-Smith, professor of emerging infectious diseases at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, told The Guardian: “Like most vaccinologists, I don’t think this vaccine will be ready before 18 months.”

As the paper notes, most vaccines take a decade or more to get regulatory approval, meaning that 18 months would be “extremely fast”.

Vox quotes Nathan Grubaugh, an epidemiologist at Yale, as saying: “Without an effective vaccine, I don’t know how this ends before millions of infections.” But a vaccine will take time to develop: that’s why public health officials have a vital role to play in helping slow the rate of infection.

The race to produce a coronavirus vaccine has already started – but Vox warns it could take “a year or more before the safety and efficacy” of new treatments can be proven.

Will summer temperatures make the virus ‘go away’?

US President Donald Trump has alarmed experts by spreading misinformation about the outbreak – but could his claim that the virus might “go away” in April when warmer weather hits the US and Europe be true?

There is no way of knowing the answer to that yet, says the Post. WHO expert Maria Van Kerkhove was not optimistic, telling the paper: “Right now there’s no reason to think this virus would act differently in different climate settings. We’ll have to see what happens as this progresses.”

In the first study looking at the affect of weather on the virus, researchers at Harvard University concluded that higher temperature and humidity “will not necessarily lead to declines in case counts”.

Worryingly, a study published the next day by scientists in looking at data from Wuhan found that “the virus seems to spread better in summery weather” and “cold air destroys the virus”, says New Scientist.

Antibody testing

Antibody blood tests that show a person has had the virus and is now resistant to it are set to come to the UK within weeks are could be a “game changer”, reports The Guardian, “allowing key workers out of isolation, for instance to reopen schools”.

The health secretary, Matt Hancock, has said the government had bought 3.5m antibody tests, but the Guardian said the UK had actually ordered 40m. “It is the sort of drastic gamble that governments around the world are taking, afraid that stocks will disappear,” says the paper.

The 3.5m tests already purchased are being tested in UK labs to check that they really work.

-

Political cartoons for February 22

Political cartoons for February 22Cartoons Sunday’s political cartoons include Black history month, bloodsuckers, and more

-

The mystery of flight MH370

The mystery of flight MH370The Explainer In 2014, the passenger plane vanished without trace. Twelve years on, a new operation is under way to find the wreckage of the doomed airliner

-

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrest

5 royally funny cartoons about the former prince Andrew’s arrestCartoons Artists take on falling from grace, kingly manners, and more

-

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?Talking Point The Trump administration is applying the pressure, and with Latin America swinging to the right, Havana is becoming more ‘politically isolated’

-

Trump touts pledges at 1st Board of Peace meeting

Trump touts pledges at 1st Board of Peace meetingSpeed Read At the inaugural meeting, the president announced nine countries have agreed to pledge a combined $7 billion for a Gaza relief package

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC head

NIH director Bhattacharya tapped as acting CDC headSpeed Read Jay Bhattacharya, a critic of the CDC’s Covid-19 response, will now lead the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

-

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?Today's Big Question After rushing to praise the initiative European leaders are now alarmed

-

Witkoff and Kushner tackle Ukraine, Iran in Geneva

Witkoff and Kushner tackle Ukraine, Iran in GenevaSpeed Read Steve Witkoff and Jared Kushner held negotiations aimed at securing a nuclear deal with Iran and an end to Russia’s war in Ukraine

-

Kurt Olsen: Trump’s ‘Stop the Steal’ lawyer playing a major White House role

Kurt Olsen: Trump’s ‘Stop the Steal’ lawyer playing a major White House roleIn the Spotlight Olsen reportedly has access to significant US intelligence