Judy Chicago interview: Dior Lady Art 5

American artist talks Dior and the art of collaboration

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Last year, a delivery of Dior womenswear was addressed to the Belen Hotel. L-shaped and built from red brick, the 1907-finished property in the New Mexico city of Belen originally served as a boarding house for Santa Fe Railway employees working in the American Southwest. Since 1996, the historic site has been the home and workplace of Judy Chicago and the artist’s third husband Donald Woodman, a photographer.

Dior had sent a selection of outfits for an upcoming portrait of Chicago, shot to illustrate a newspaper profile of Maria Grazia Chiuri – the Parisian brand’s first female creative director – who had named the artist among her list of 11 influential women. “They sent me clothes to wear for the photoshoot, including bags,” Chicago remembers. “I said, ‘Right, I am going to paint with a bag on my arm!’”

At the time of our interview, both New Mexico and the United Kingdom are back in lockdown to curb the spread of coronavirus, and so we speak through video call. On screen, Chicago, 81, makes a striking appearance: the artist matches her preferred working uniform – T-shirts, jeans and sweatshirts – with a curly hairdo dyed a regal purple. Her work has been exhibited worldwide and features in the permanent collections in institutions including MoMA (New York), London’s Tate Modern and the Moderna Museet in Stockholm. Today on camera, Chicago’s enthusiasm for her trade and its many possibilities are not lost, and she peppers statements and reminiscences with bouts of wholehearted laughter.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

There’s cinematic scope to Chicago’s biography. Born Judith Cohen in 1939, she was raised in Chicago by her mother – May, a former dancer turned medical secretary – and her father Arthur Cohen. A trade union organiser who worked the nightshift at a local post office, Arthur Cohen was an active supporter of the American Communist Party; he was also the scion of a long lineage of rabbis. Encouraged by her mother, Chicago identifies art to be her calling from early childhood.

She eventually received her Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) in 1962, followed by a Master’s degree two years later. Then and now, the artist’s work researches and redresses the role of women in history, culture and society, a theme she has expressed through diverse mediums, mastering acrylic lacquers, plastics, ceramics, stained glass, fireworks and a number of textile crafts. Chicago says: “I have tried to deal with subjects that are outside of the traditional subjects of art, and in a way new content requires new forms.”

In 1970, she used print media to make known her new name: an advert for an upcoming gallery show re-introduced the artist as Judy Chicago, supplanting her first husband’s surname (Gerowitz) with the name of her hometown, thereby freeing herself from all male-dominated appellation.

Chicago’s work is striking for its inclusivity, recognising art as a medium to inspire thought and action in others. As an educator, Chicago in 1971 launched the United States’ inaugural feminist art course when teaching at California’s Fresno State College. As an activist, she founded non-profit feminist set-up Through the Flower in 1978. Then, there are Chicago’s artworks and initiatives, which are often realised in collaboration with volunteers and fellow creatives.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Partnering with artist Miriam Schapiro, Chicago opened Womanhouse, a pioneering group exhibition of feminist art, in 1971. Eight years later, in the spring of 1979, she unveiled what would arguably become her most cited work at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art: centred on a triangle-shaped banquette, Chicago’s The Dinner Party counts 39 place settings, assembled for an all-female guest list that includes Archaic Greek lyric poet Sappho, the 14th century Saint Brigid of Kildare, Virginia Woolf and 19th century American poet Emily Dickinson. Guests names are stitched in gold thread on table runners decorated with detailed embroideries and matched with hand-painted ceramic plates.

The Dinner Party took Chicago and a workforce of 400 volunteers – their help commemorated with inscriptions on Acknowledgement Panels – six years to complete. “My collaborations are very different to a lot of other artists. I am involved in every step of the collaboration,” she says. “Also, I don’t want the people I work with to be like robots. I want them to bring their best to the collaboration, I want to create projects or images that allow my collaborators to bring their skills and their ideas to it because I believe that’s the way to get the best result.” Eventually, the artwork would be viewed by more than one million visitors attending exhibitions in 16 venues across three continents.

In 1980, she called upon the help of 150 needleworkers for her Birth Project: over a period of five years, Chicago and team set about capturing images of childbirth in many dozens of panels celebrating motherhood, using an array of handicrafts including needlepoint embroidery, batik dyeing, quilting and filet crochet, all mixed with painting. “Collaboration is really kind of an extension of one’s own hand,” Chicago explains. “Sometimes, work requires more than one hand. More than one skill.”

Following that first delivery to the Belen Hotel, Chicago’s affiliation with Dior gained momentum. That year, in the autumn Chicago and Chiuri talked over possible team-ups. At Dior, the fine arts are part of the brand’s DNA: the maison’s founder Christian Dior worked as a gallerist before changing professions and eventually setting up his business in December 1946. Since her 2016 appointment, Chiuri has made use of her platform to highlight the work of female artists – among them Argentinian surrealist painter Leonor Fini – and the late New York art historian Linda Nochlin.

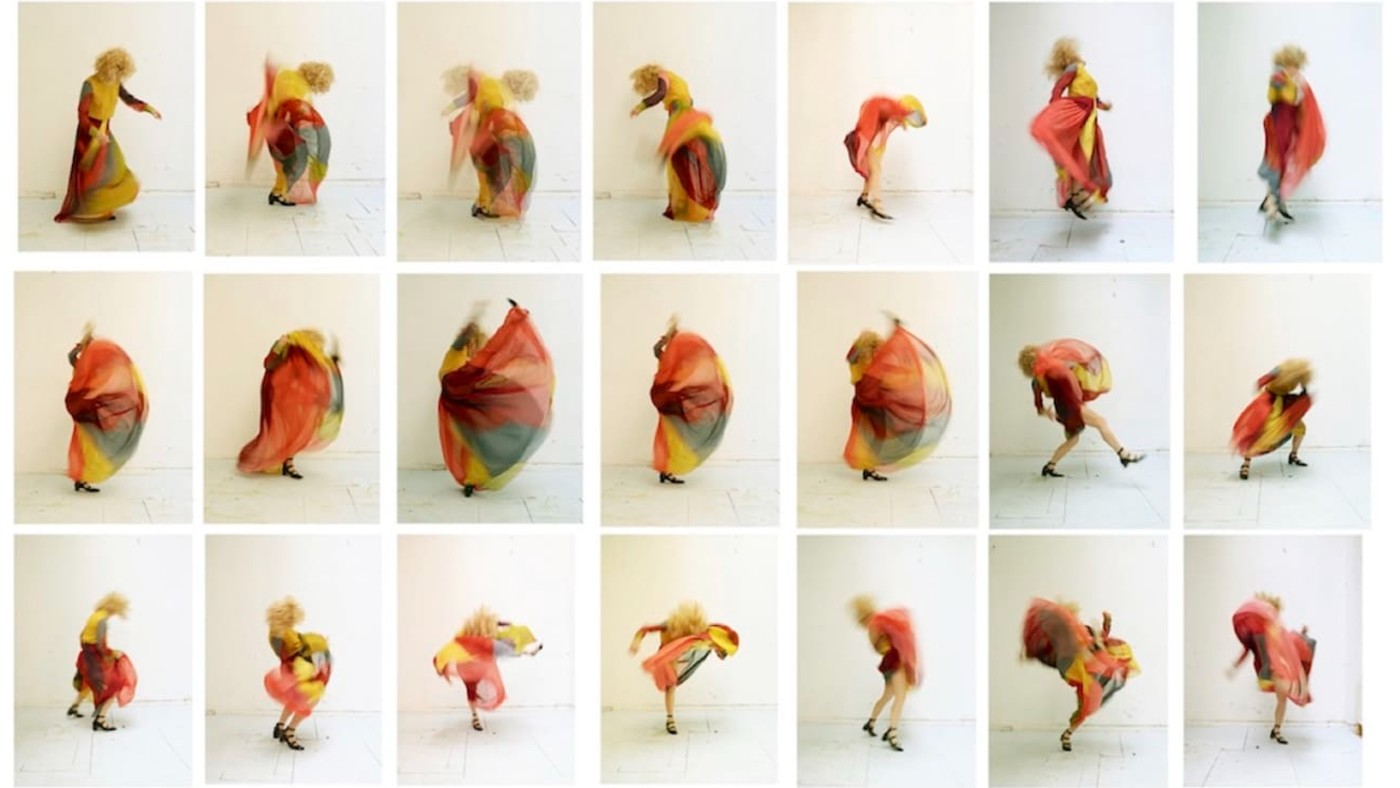

In January 2020, the result of their combined forces took bulbous shape in the gardens of Paris’ Musée Rodin. Informed by her research into the role of goddesses across centuries and cultures, Chicago had first envisioned her Inflatable Mother Goddess in 1977; in tandem with Dior and production company Bureau Betak, she now realised her public sculpture, which doubled as the tent-like venue for Chiuri’s Spring / Summer 2020 haute couture show. On the day of the show, models dressed in Chiuri’s designs passed 20 banners each measuring three metres in length. Each banner elaborated on Chicago’s question: “What If Women Ruled the World?” with musings – “Would there be violence?” “Would buildings resemble wombs?” “Would God be female?” – all spelt-out in hand-embroideries and the work of the Indian Chanakya School of Craft. Located in Mumbai, the school and its foundation advocates women's empowerment through education. Chicago says: “They [were] not only giving them embroidery instructions, they were having conversations about the meaning of the questions.”

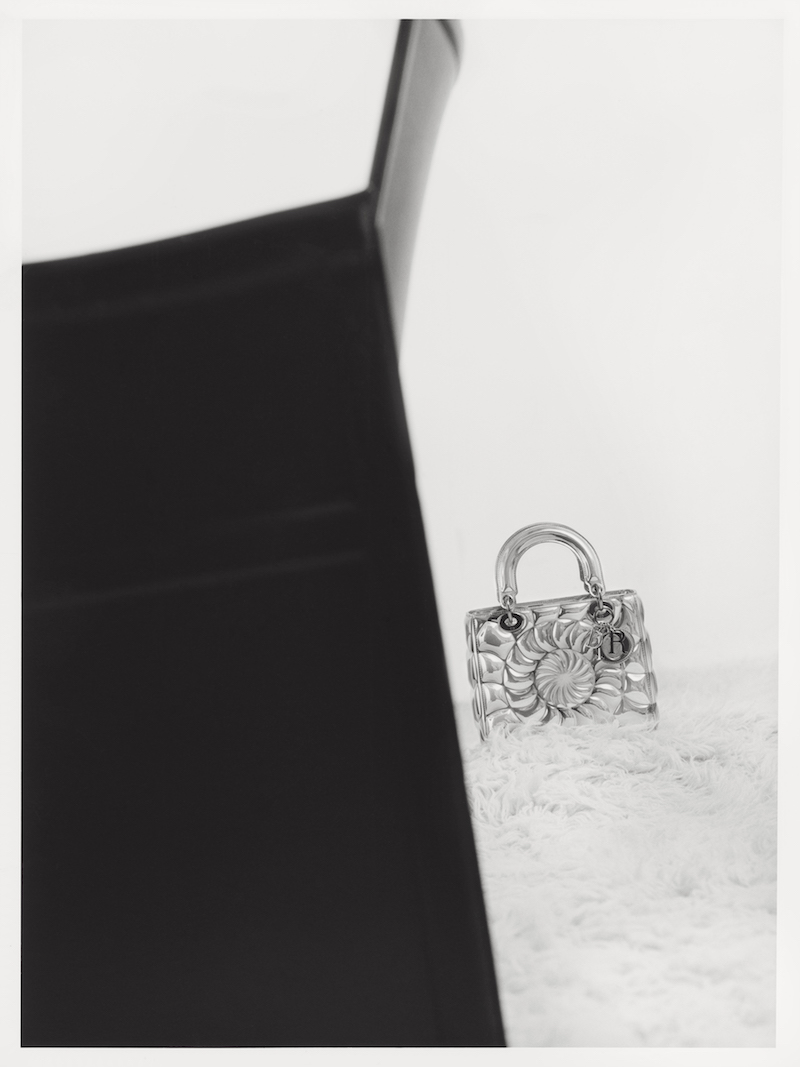

It was while she was busy perfecting these banners that Dior approached Chicago with a second possible partnership, inviting the artist to join nine others for this year’s iteration of the maison’s Lady Art initiative. An ambitious undertaking, Dior’s Lady Art has since its 2016 launch invited a number of contemporary artists active around the world to put their stamp on the brand’s best-loved Lady Dior, an architecturally-shaped handbag first launched in 1994. To date, the brand has signed up an inspired list of collaborators: Friedrich Kunath, Mat Collishaw, Mickalene Thomas and Marguerite Humeau have all dreamt up Lady Diors, fabricated by the make’s skilled artisans in limited editions.

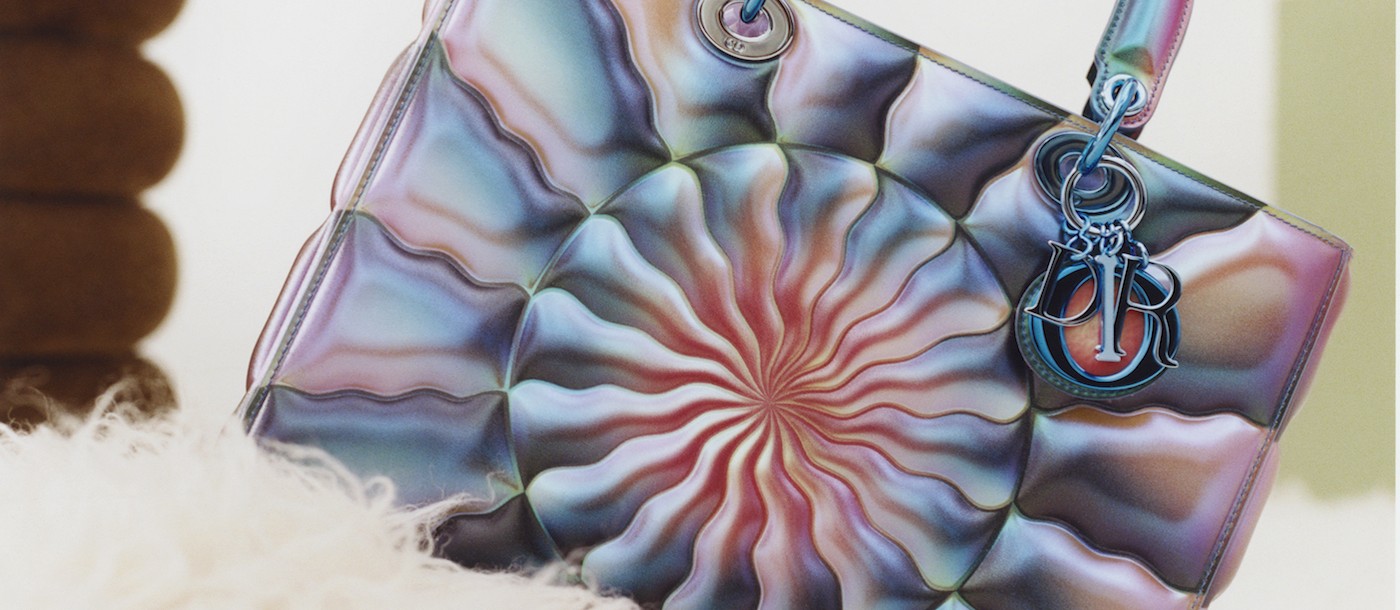

“When I do something, especially something I have never done before it starts out with research,” Chicago tells me. “I was thinking I had to research the history of purses and the history of the Lady Dior bags.” Chicago instead decided to adapt an archival artwork, with the help of husband Donald. Digitally manipulating her two-dimensional paintings to fit the Lady Dior’s blueprint, they had a first success with Let It All Hang Out, a 1973 sprayed acrylic on canvas depiction of spiralling shell-like shapes in pinks, purple and yellow.

In Paris, the Dior team presented Chicago with myriad options of recreating her artwork. A technical fabric embossed with a high-frequency dichroic effect made the cut. “I just flipped!” says Chicago of first seeing the reflective treatment. “I know about the process, it just never occurred to me that it would lend itself so incredibly to my images.”

Their first creation deemed a success, Dior tasked Chicago with selecting two additional artworks to be commemorated. Chicago now trialled artworks from her 1972 Great Ladies series, which expresses the personalities and biographies of historical queens in curling, twisting motifs. Her take on 17th century Christina, Queen of Sweden inspired a small and iridescent Lady Dior; Chicago’s 1973 Queen Victoria is emblazoned across a larger version of the accessory. The name of each monarch is inscribed on the bottom of respective bags. “Queen Victoria would probably like the fact that she’s the biggest!” Chicago muses. “I was thinking how delicious it would be to teach women’s history through a bag.”

From a show venue to limited edition accessory, Judy Chicago’s partnership with Dior has been multifaceted and across borders. “It brought my ideas and my art to a global audience, because Dior has a global platform,” Chicago decrees. “It was the greatest creative opportunity I have ever had in my life.”

-

Democrats push for ICE accountability

Democrats push for ICE accountabilityFeature U.S. citizens shot and violently detained by immigration agents testify at Capitol Hill hearing

-

The price of sporting glory

The price of sporting gloryFeature The Milan-Cortina Winter Olympics kicked off this week. Will Italy regret playing host?

-

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?

Fulton County: A dress rehearsal for election theft?Feature Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard is Trump's de facto ‘voter fraud’ czar

-

Dior’s Lady 95.22 bag: high frequency, high style, high society

Dior’s Lady 95.22 bag: high frequency, high style, high societyUnder the Radar Maria Grazia Chiuri’s Lady 95.22 is a celebration of craft

-

Christian Dior and Roger Vivier: the power of two

Christian Dior and Roger Vivier: the power of twoUnder the Radar A new shoe celebrates the partnership between legendary couturier Christian Dior and influential designer Roger Vivier

-

A Dior icon: Martino Gamper explains his medallion chair

A Dior icon: Martino Gamper explains his medallion chairUnder the Radar ‘People come and go yet the chairs remain,’ the Italian designer said

-

Maria Grazia Chiuri interview: Dior is ready to celebrate

Maria Grazia Chiuri interview: Dior is ready to celebratefeature Designing a Dior for the post-pandemic world

-

High time to have a ball: Dior Grand Soir Plissé Précieux

High time to have a ball: Dior Grand Soir Plissé PrécieuxSpeed Read A new haute couture timepiece by Dior

-

Fashion designer Kim Jones: Transforming Dior

Fashion designer Kim Jones: Transforming DiorIn Depth English fashion designer Jones has applied his Midas touch to Dior menswear

-

Exclusive interview with Dior’s Maria Grazia Chiuri

Exclusive interview with Dior’s Maria Grazia ChiuriIn Depth The maison’s artistic director explains her vision of femininity

-

Maison de Choup: ethical clothing down to a Tee

Maison de Choup: ethical clothing down to a TeeThe Week Recommends How a fashion label born from anxiety is helping Kate Middleton fight the stigma of mental illness