HIV researchers edge closer to a cure

British man with HIV hoping to be cured of the disease after unprecedented collaboration between universities

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

British scientists could be on the brink of finding a cure for HIV with a pioneering new therapy designed to eradicate the virus.

An unprecedented collaboration between the universities of Oxford, Cambridge, Imperial College London, University College London and King's College London is being backed by the NHS, which could save millions of pounds in reduced treatment costs.

How does it work?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The HIV virus infects T-cells, white blood cells that play an important role in the immune system. If the T-cell is active, the HIV virus multiplies to infect other T-cells – something that can be suppressed by anti-retroviral therapies (Art). However, Art is unable to target T-cells when they are not active, so only acts as a control for HIV rather than a cure.

The new therapy will target the HIV reservoir in these dormant cells, by first boosting the patient's immune system, allowing it to spot HIV-infected T-cells, and then using a drug to activate the dormant T-cells so they can be found and destroyed.

"This is the first therapy to track down and destroy the HIV in every part of the body, including in the dormant cells that evade current treatments", says the Sunday Times.

It's a "huge challenge", says Mark Samuels, the managing director of the National Institute for Health Research, and it is "still early days", but the progress has been "remarkable", he adds.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Will it work?

Laboratory tests have proved successful and scientists are now trying the therapy on their first patient, a 44-year-old British man.

Early tests show the virus is undetectable in the man's blood but he will have to wait some months before confirmation of whether the treatment has permanently cleared the disease.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

The truth about vitamin supplements

The truth about vitamin supplementsThe Explainer UK industry worth £559 million but scientific evidence of health benefits is ‘complicated’

-

The stalled fight against HIV

The stalled fight against HIVThe Explainer Scientific advances offer hopes of a cure but ‘devastating’ foreign aid cuts leave countries battling Aids without funds

-

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancer

Covid-19 mRNA vaccines could help fight cancerUnder the radar They boost the immune system

-

Bluetoothing: the phenomenon driving HIV spike in Fiji

Bluetoothing: the phenomenon driving HIV spike in FijiUnder the Radar ‘Blood-swapping’ between drug users fuelling growing health crisis on Pacific island

-

Deadly fungus tied to a pharaoh's tomb may help fight cancer

Deadly fungus tied to a pharaoh's tomb may help fight cancerUnder the radar A once fearsome curse could be a blessing

-

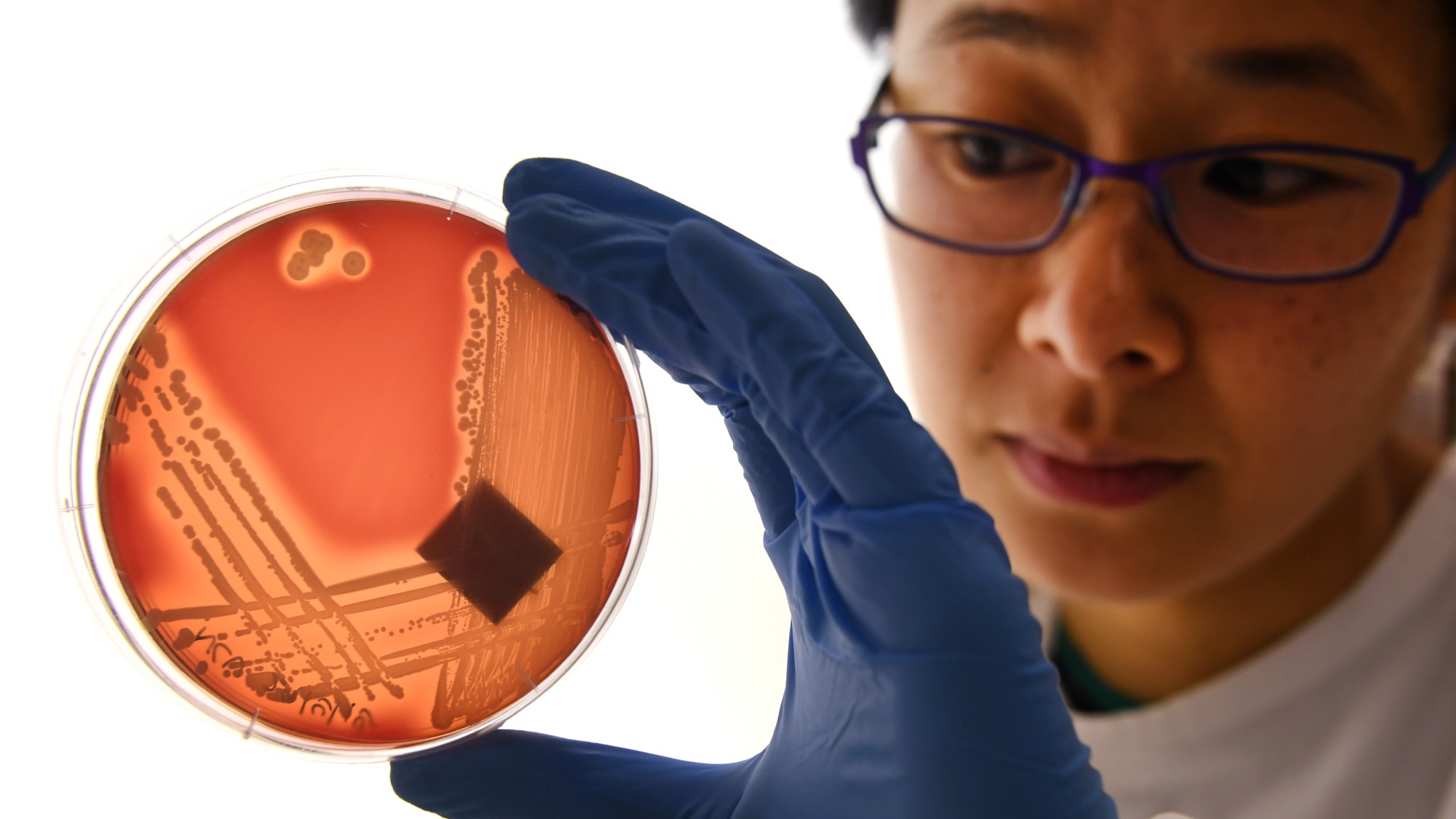

'Poo pills' and the war on superbugs

'Poo pills' and the war on superbugsThe Explainer Antimicrobial resistance is causing millions of deaths. Could a faeces-filled pill change all that?

-

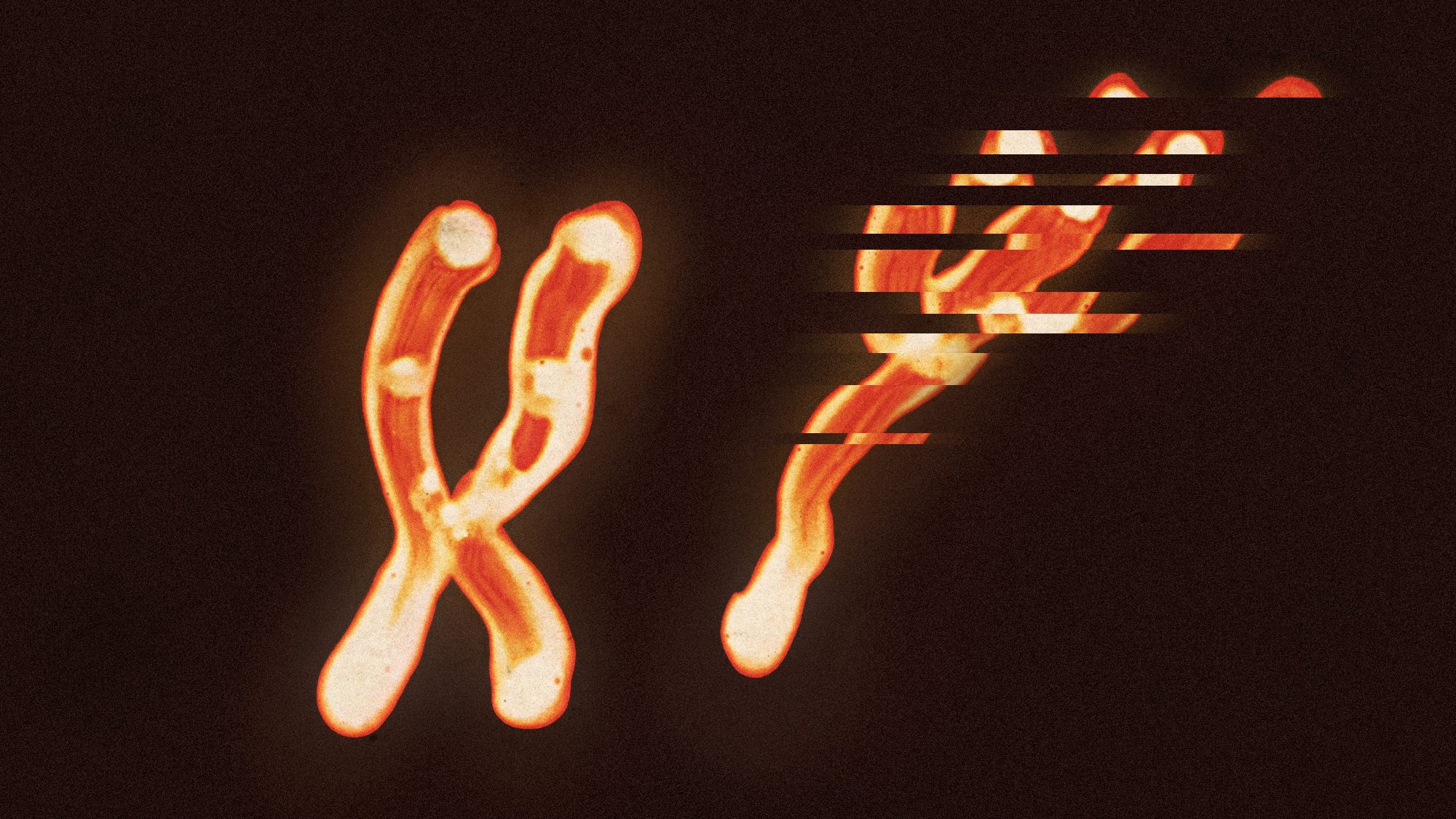

The Y chromosome degrades over time. And men's health is paying for it

The Y chromosome degrades over time. And men's health is paying for itUnder the radar The chromosome loss is linked to cancer and Alzheimer's

-

A bacterial toxin could be contributing to the colorectal cancer rise in young people

A bacterial toxin could be contributing to the colorectal cancer rise in young peopleUnder the radar Most exposure occurs in childhood