Hiroshima anniversary: 75 years since the atom bomb

Japanese city marks nuclear attack that resulted in hundreds of thousands of deaths

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

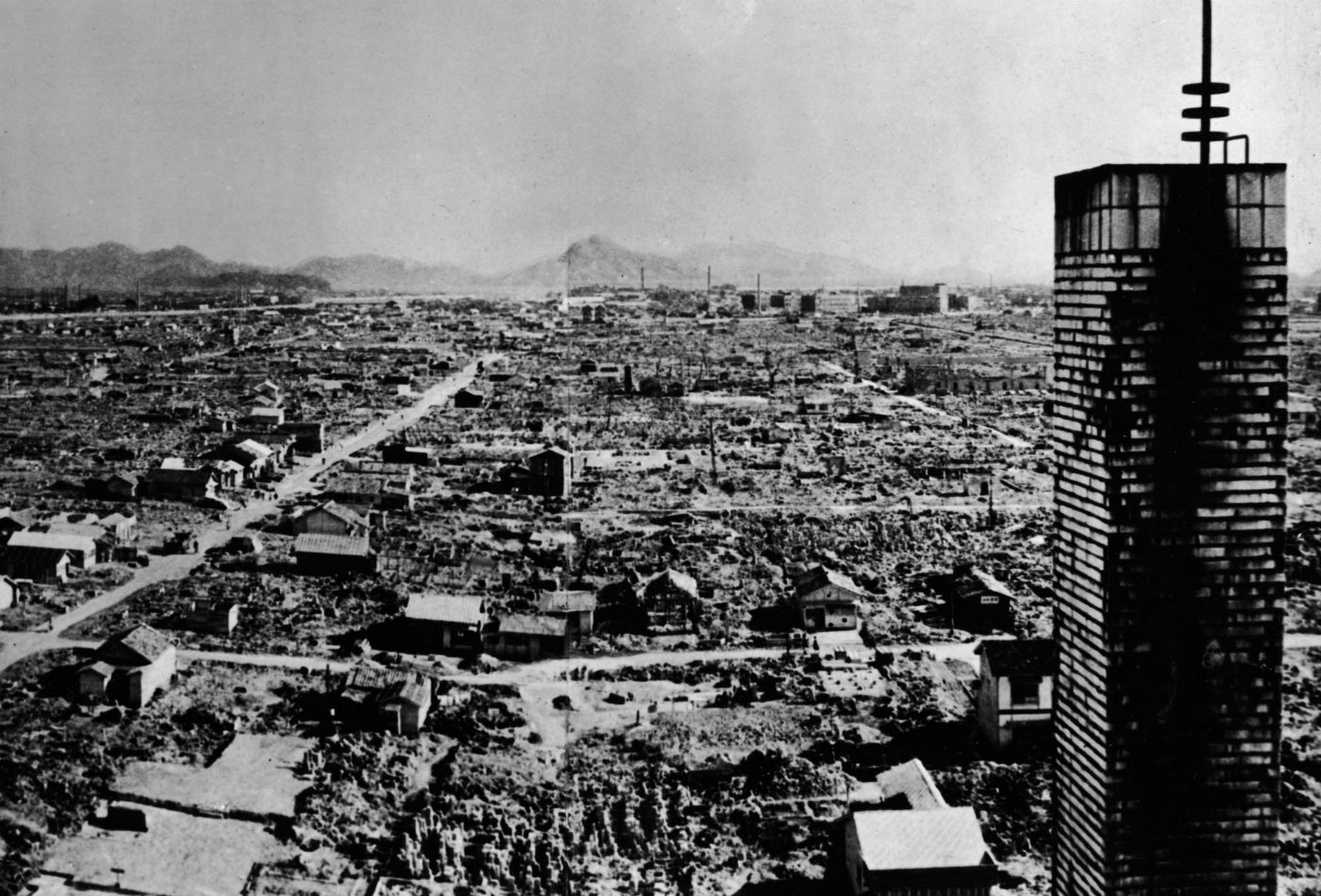

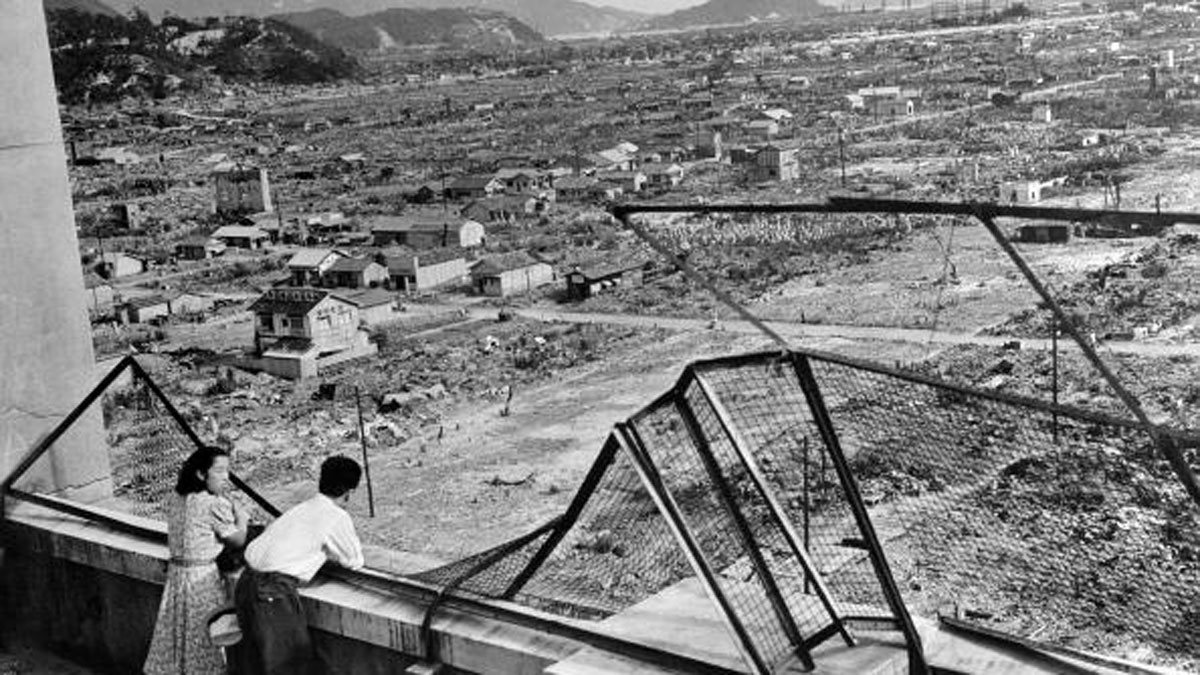

The first of the only two nuclear weapons ever used in anger fell on the Japanese city of Hiroshima 75 years ago today, on 6 August 1945.

Today, bells rung out across the city to mark the anniversary of the devastating bombing, which instantly killed at least 80,000 people and soon forced Japan to surrender, bringing the Second World War to an end

It was, as NPR puts it, the “blast that changed the world”.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Memorial events were “scaled back this year because of the pandemic”, the BBC says, but on Thursday, Japan's Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and the mayor of Hiroshima joined bomb survivors and their descendants in the city's Peace Park, which doubles as a monument to those killed in the bombing.

In his speech, Abe restated Japan’s commitment to its long-standing nuclear weapons ban as the only country to have suffered the full effects of an atomic bomb.

“Japan's position is to serve as a bridge between different sides and patiently promote their dialogue and actions,” Abe said, adding that he would “do [his] best for the realisation of a world without nuclear weapons and peace for all time”.

The ethics of the bombing have long been a subject of debate. Some believe it to have been a war crime; an act of disproportionately destructive chemical warfare on a civilian population. Others believe it saved Japan - and millions of Allied soldiers - from a costly land invasion led by the US.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

So what happened at Hiroshima in 1945, and how are the effects still being felt?

What happened?

At 8.15am local time on 6 August, 1945, American pilots dropped the world’s first atom bomb on the city of Hiroshima. It unleashed the equivalent of 12,500 tons of TNT and was more than 2,000 times as powerful as the largest bomb ever used before. At least 80,000 people were killed instantly by the explosion and another 60,000 were dead by the end of the year, representing almost half of the city’s total population.

“Hundreds upon hundreds of the dead were so badly burned in the terrific heat generated by the bomb that it was not even possible to tell whether they were men or women, old or young,” reported Wilfred Burchett, the first journalist to enter the city.

“Of thousands of others, nearer the centre of the explosion, there was no trace. They vanished. The theory in Hiroshima is that the atomic heat was so great that they burned instantly to ashes – except that there were no ashes.”

Many of those who survived suffered long-term illness and disability from the radiation, including cancers, tumours and birth defects. Three days after the attack on Hiroshima, the city of Nagasaki was destroyed in a second nuclear blast, which killed 74,000 people.

After the first bomb fell, co-pilot Captain Robert Lewis said: “My God, what have we done? How many did we kill?”

Why?

Hiroshima was targeted because of its strategic significance as a military headquarters, a major trading port and one of the main supply depots for the Japanese army. It was also largely untouched by previous bombings. President Harry Truman said the city had been chosen so that “soldiers and sailors are the target and not women and children”. However, the Stop the War Coalition points out that over 95% of the combined casualties of the two cities were civilian.

The US government argued that the use of such weapons of mass destruction was the only way to avoid full-blown war with Japan and bring about a quick conclusion to WWII. Truman repeatedly defended his decision to destroy the two cities, arguing that the bombs “saved the lives of half a million of our boys”. The US government got their wish - Japan surrendered to the Allies on 14 August 1945.

But in an interview with Newsweek in 1963, Truman's successor Dwight Eisenhower revealed that even he had reservations about using the atomic weapon, saying: “The Japanese were ready to surrender and it wasn’t necessary to hit them with that awful thing.”

The legacy of the A-bomb

As the first country to use nuclear weapons against civilian populations, the US was in direct violation of internationally agreed principles of war, writes Professor Rodrigue Tremblay for the Global Research Centre. “Thus, August 1945 is a most dangerous and ominous precedent that marked a new dismal beginning in the history of humanity, a big moral step backward.”

The bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki also changed the course of history by launching the global race for nuclear proliferation. Currently, just nine countries are known to possess nuclear weapons: the US, the UK, France, Israel, Russia, China, India, Pakistan and North Korea.

These nations believe strongly in nuclear deterrence, arguing that by possessing a range of weapons, foreign states will refrain from attacking owing to the fear of retaliation and “mutually assured destruction”. As such, hopes of nuclear disarmament deals look likely to be disappointed.

As The Guardian’s Andrew Anthony asks: “In a world in which a rogue state like North Korea, a dysfunctional state like Pakistan and an increasingly bellicose state like Russia all possess the bomb, what major power is going to lead the way and unilaterally disarm?”

The first of the only two nuclear weapons ever used in anger fell on the Japanese city of Hiroshima 75 years ago today, on 6 August 1945.

Today, bells rung out across the city to mark the anniversary of the devastating bombing, which instantly killed at least 80,000 people and soon forced Japan to surrender, bringing the Second World War to an end

It was, as NPR puts it, the “blast that changed the world”.

https://www.npr.org/2020/08/06/899593615/hiroshima-atomic-bombing-raising-questions-75-years-later

Memorial events were “scaled back this year because of the pandemic”, the BBC says, but on Thursday, Japan's Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and the mayor of Hiroshima joined bomb survivors and their descendants in the city's Peace Park, which doubles as a monument to those killed in the bombing.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-53660059

In his speech, Abe restated Japan’s commitment to its long-standing nuclear weapons ban as the only country to have suffered the full effects of an atomic bomb.

“Japan's position is to serve as a bridge between different sides and patiently promote their dialogue and actions,” Abe said, adding that he would “do [his] best for the realisation of a world without nuclear weapons and peace for all time”.

The ethics of the bombing have long been a subject of debate. Some believe it to have been a war crime; an act of disproportionately destructive chemical warfare on a civilian population. Others believe it saved Japan - and millions of Allied soldiers - from a costly land invasion led by the US.

So what happened at Hiroshima in 1945, and how are the effects still being felt?

-

‘The West needs people’

‘The West needs people’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Filing statuses: What they are and how to choose one for your taxes

Filing statuses: What they are and how to choose one for your taxesThe Explainer Your status will determine how much you pay, plus the tax credits and deductions you can claim

-

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – an ‘engrossing’ exhibition

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – an ‘engrossing’ exhibitionThe Week Recommends All 126 images from the American photographer’s ‘influential’ photobook have come to the UK for the first time

-

US, Russia restart military dialogue as treaty ends

US, Russia restart military dialogue as treaty endsSpeed Read New START was the last remaining nuclear arms treaty between the countries

-

What happens now that the US-Russia nuclear treaty is expiring?

What happens now that the US-Russia nuclear treaty is expiring?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION Weapons experts worry that the end of the New START treaty marks the beginning of a 21st-century atomic arms race

-

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK government

Epstein files topple law CEO, roil UK governmentSpeed Read Peter Mandelson, Britain’s former ambassador to the US, is caught up in the scandal

-

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishes

Iran and US prepare to meet after skirmishesSpeed Read The incident comes amid heightened tensions in the Middle East

-

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from Gaza

Israel retrieves final hostage’s body from GazaSpeed Read The 24-year-old police officer was killed during the initial Hamas attack

-

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purge

China’s Xi targets top general in growing purgeSpeed Read Zhang Youxia is being investigated over ‘grave violations’ of the law

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mine

Why Greenland’s natural resources are nearly impossible to mineThe Explainer The country’s natural landscape makes the task extremely difficult