Jean Dubuffet exhibition: Brutal Beauty at the Barbican

One of the great post-war artists, Dubuffet took ugliness and ‘fashioned it into something extraordinary’

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In October 1944, an exhibition opened in Paris that scandalised the newly liberated city’s art world, said Jonathan Jones in The Guardian. The artist responsible was Jean Dubuffet, a middle-aged provincial wine seller who had never before shown his work in public – but whose art made the ageing avant-garde movements of the time look tame.

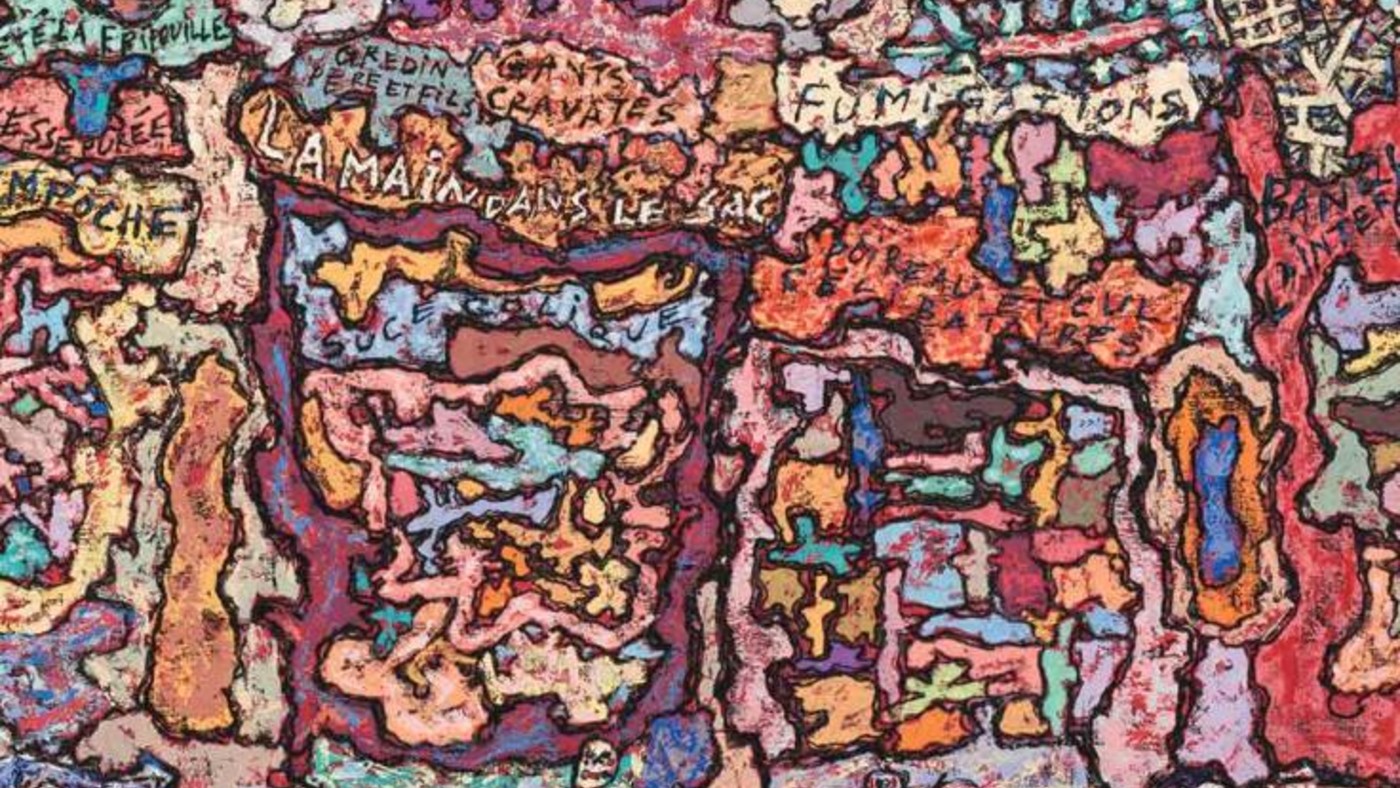

Dubuffet (1901-1985) looked not to art galleries for inspiration, but to the city’s graffiti-strewn walls, faithfully reproducing them in scrappy collages that made no concession to prettiness. His palette – “a melange of snot greens, piss yellows and shit browns” – could hardly have been uglier. His materials were not just oil, paint and clay, but urban detritus: dirt, broken glass, discarded newspapers, even dead insects. Most shocking of all was that Dubuffet seemingly “abandoned all pretence at skill”, in effect rejecting every rule of good taste. Yet, against the odds, he would come to be regarded as one of the most influential artists of his time: his ideas are “everywhere” in the art world today. When it opens its doors on 17 May, the Barbican will host the first major Dubuffet exhibition to be held in Britain for 50 years, bringing together a broad selection of his “anti-art”, and showing how he took ugliness and “fashioned it into something extraordinary”.

Dubuffet did not dedicate himself to art until his 40s, said Claire Selvin in Artnews. Although he had studied painting in Paris as a young man, he had bridled at the rigidity of how art was taught, and quit in disgust, spending 20 years working in the wine trade, while maintaining contact with the prime movers of the surrealist movement. Crucial to his work was his interest in untrained – or “outsider” – artists, particularly the mentally ill. Their work, he believed, revealed much more about the human subconscious than anything that came out of the tasteful dogmas of modernism. “I have a great interest in madness, and I am convinced art has much to do with madness,” he explained. His early works replicated the untutored visions of the outsiders he admired: he painted childlike scenes depicting passengers on the metro, Parisian crowds and jazz concerts, sometimes incorporating unusual materials – “cement, foil, tar, gravel” – to blur “the boundary between painting and sculpture”.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

In one “notorious” 1947 show, Dubuffet even presented a portrait that purported to be fashioned from chicken droppings, said Laura Cumming in The Observer. Outraged Parisians “showed their disgust in organised protests”. Yet paradoxically, he was not an artist without skill. His sculptures are often wonderful: his portrait of Antonin Artaud sees the playwright “perfectly defined as a labyrinth of live wires”. By the 1960s, Dubuffet had become feted in both France and America, where he made several “gargantuan” sculptures. Composed of “giant cut-out figures, like vast jigsaw pieces”, they lacked the immediacy of his earlier work, but proved an enormous influence on the likes of Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat. The defining characteristic of his art was an “impish” sense of humour. And while his works might seem unserious by comparison to the angst-ridden efforts of contemporaries, such as Alberto Giacometti or Francis Bacon, Dubuffet was unquestionably “one of the great artists of postwar Europe”.

Barbican Centre, London EC2 (barbican.org.uk). From 17 May to 22 August

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

The environmental cost of GLP-1s

The environmental cost of GLP-1sThe explainer Producing the drugs is a dirty process

-

Nuuk becomes ground zero for Greenland’s diplomatic straits

Nuuk becomes ground zero for Greenland’s diplomatic straitsIN THE SPOTLIGHT A flurry of new consular activity in Nuuk shows how important Greenland has become to Europeans’ anxiety about American imperialism

-

‘This is something that happens all too often’

‘This is something that happens all too often’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ return

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ returnThe Week Recommends Carrie Cracknell’s revival at the Old Vic ‘grips like a thriller’

-

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ love letter to Lagos

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ love letter to LagosThe Week Recommends Akinola Davies Jr’s touching and ‘tender’ tale of two brothers in 1990s Nigeria

-

Send Help: Sam Raimi’s ‘compelling’ plane-crash survival thriller

Send Help: Sam Raimi’s ‘compelling’ plane-crash survival thrillerThe Week Recommends Rachel McAdams stars as an office worker who gets stranded on a desert island with her boss

-

Book reviews: ‘Hated by All the Right People: Tucker Carlson and the Unraveling of the Conservative Mind’ and ‘Football’

Book reviews: ‘Hated by All the Right People: Tucker Carlson and the Unraveling of the Conservative Mind’ and ‘Football’Feature A right-wing pundit’s transformations and a closer look at one of America’s favorite sports

-

Catherine O'Hara: The madcap actress who sparkled on ‘SCTV’ and ‘Schitt’s Creek’

Catherine O'Hara: The madcap actress who sparkled on ‘SCTV’ and ‘Schitt’s Creek’Feature O'Hara cracked up audiences for more than 50 years

-

6 gorgeous homes in warm climes

6 gorgeous homes in warm climesFeature Featuring a Spanish Revival in Tucson and Richard Neutra-designed modernist home in Los Angeles

-

Touring the vineyards of southern Bolivia

Touring the vineyards of southern BoliviaThe Week Recommends Strongly reminiscent of Andalusia, these vineyards cut deep into the country’s southwest

-

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – an ‘engrossing’ exhibition

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – an ‘engrossing’ exhibitionThe Week Recommends All 126 images from the American photographer’s ‘influential’ photobook have come to the UK for the first time