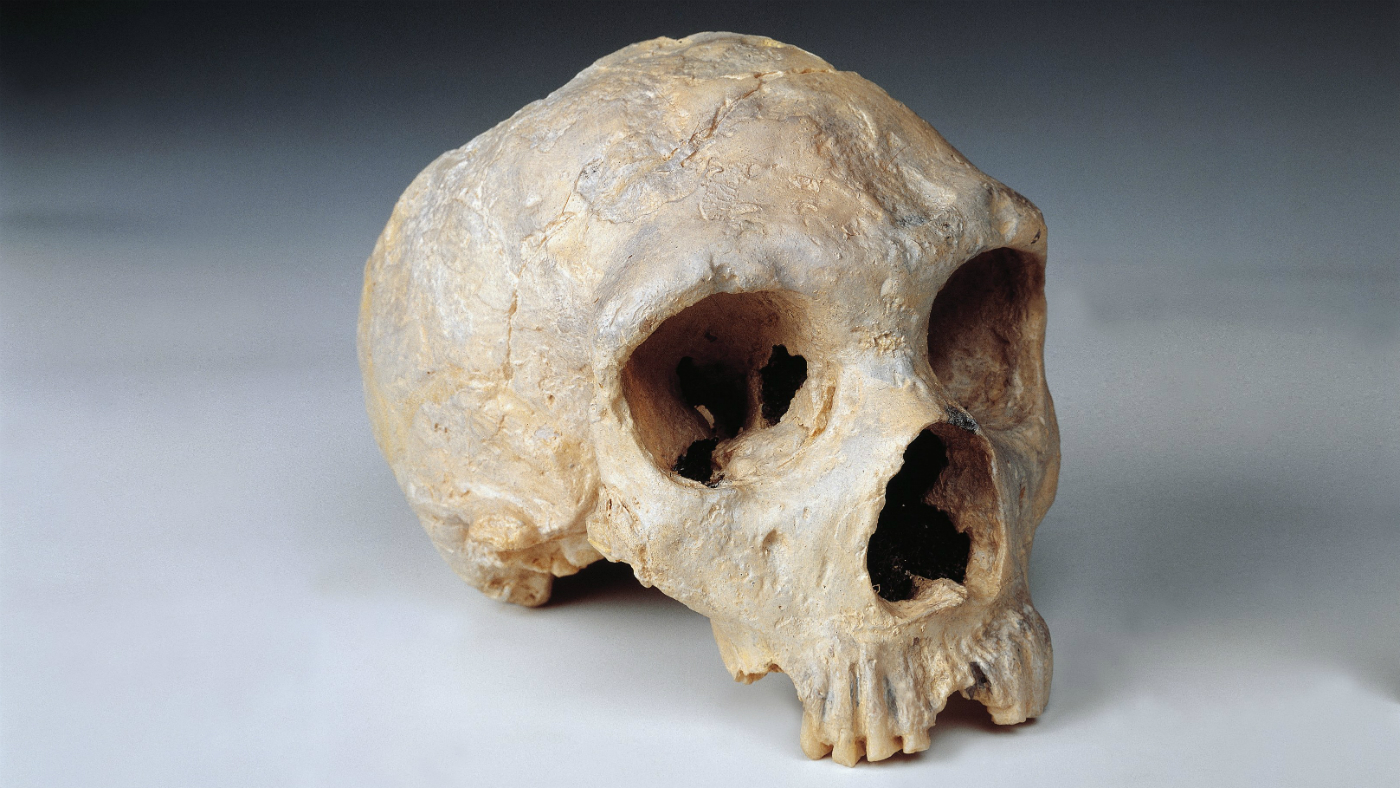

How the shape of your skull can reveal Neanderthal DNA

Scientists uncover traces of Neanderthal genes linked with ‘less round brains’ in modern humans

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Modern humans with slightly elongated skull shapes may share rare genetic material inherited from Neanderthals, our closest extinct relatives, new research suggests.

Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, have identified Neanderthal DNA fragments in modern human chromosomes 1 and 18 that are linked with less round brains.

The study, described in a paper published in the journal Current Biology, found that the Neanderthal DNA only makes up around 1% to 2% of the total of any modern European human. The effect on the shape of the skull is “too small to be seen with the naked eye, but shows up on brain scans”, New Scientist reports.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Senior study author Professor Simon Fisher described the effects of the DNA on the skull as “very subtle”, but added that the team had detected them across a large sample size of nearly 4,500 MRI brain scans of European subjects. Scientists believe the genetic material was passed down through multiple episodes of interbreeding between humans and their Neanderthal cousins.

“The Neanderthal variants lead to small changes in gene activity and only push people slightly towards a less globular brain shape,” Fisher explained.

However, the researchers also noted that both of the brain regions in which the Neanderthal fragments were discovered - UBR4 and PHLPP1 - are involved in key functions such as learning and coordinating movements, reports The Independent.

“We know from other studies that completely disrupting UBR4 or PHLPP1 can have major consequences for brain development,” Fisher said.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But as The New York Times points out, the study “wasn’t designed to determine how Neanderthal genes influence thought”, and the researchers stressed that there is currently no indication that the DNA pieces have any effect on the cognitive abilities of modern humans.

“The focus of our study is on understanding the unusual brain shape of modern humans,” said Dr Philipp Gunz, another Max Planck Institute scientist. “These results cannot be used to make inferences about what Neanderthals could or could not do.”

All the same, the study could result in future research to look for more Neanderthal DNA linked with modern human brains and “determine what specific effects these ancient genetic variants might have” by growing brain tissue containing the DNA in a laboratory, adds specialist news site Live Science.

-

AI surgical tools might be injuring patients

AI surgical tools might be injuring patientsUnder the Radar More than 1,300 AI-assisted medical devices have FDA approval

-

9 products to jazz up your letters and cards

9 products to jazz up your letters and cardsThe Week Recommends Get the write stuff

-

‘Zero trimester’ influencers believe a healthy pregnancy is a choice

‘Zero trimester’ influencers believe a healthy pregnancy is a choiceThe Explainer Is prepping during the preconception period the answer for hopeful couples?

-

Pros and cons of gene-editing babies

Pros and cons of gene-editing babiesPros and Cons Controversial scientist says he feels “unease” about the future of children whose genes he edited as embryos

-

Home Office worker accused of spiking mistress’s drink with abortion drug

Home Office worker accused of spiking mistress’s drink with abortion drugSpeed Read Darren Burke had failed to convince his girlfriend to terminate pregnancy

-

In hock to Moscow: exploring Germany’s woeful energy policy

In hock to Moscow: exploring Germany’s woeful energy policySpeed Read Don’t expect Berlin to wean itself off Russian gas any time soon

-

Were Covid restrictions dropped too soon?

Were Covid restrictions dropped too soon?Speed Read ‘Living with Covid’ is already proving problematic – just look at the travel chaos this week

-

Inclusive Britain: a new strategy for tackling racism in the UK

Inclusive Britain: a new strategy for tackling racism in the UKSpeed Read Government has revealed action plan setting out 74 steps that ministers will take

-

Sandy Hook families vs. Remington: a small victory over the gunmakers

Sandy Hook families vs. Remington: a small victory over the gunmakersSpeed Read Last week the families settled a lawsuit for $73m against the manufacturer

-

Farmers vs. walkers: the battle over ‘Britain’s green and pleasant land’

Farmers vs. walkers: the battle over ‘Britain’s green and pleasant land’Speed Read Updated Countryside Code tells farmers: ‘be nice, say hello, share the space’

-

Motherhood: why are we putting it off?

Motherhood: why are we putting it off?Speed Read Stats show around 50% of women in England and Wales now don’t have children by 30