10 crucial details from the Senate's CIA torture report

Good summaries of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence's report are here, here, and here. Here's what I found most interesting and notable, beyond the flashier headlines about, say, rectal feeding.

1. Twenty-six people who were detained should not have been detained, the CIA acknowledges. That's 26 out of 119, or 22 percent.

2. Over and over, the CIA justified ratcheting up the techniques not because it had intelligence or evidence that the detainees did know more than they were sharing, but instead to increase the CIA's own confidence that the detainees had shared everything they knew. In other words, the thinking was: "We'll enhance his interrogations until it's not possible that he could withhold actionable information from us."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"Our assumption is the objective of this operation is to achieve a high degree of confidence that [Abu] Zubaydah is not holding back actionable information concerning threats to the United States," was how Zubaydah's top interrogator put it in a cable to headquarters. Even though the CIA was telling the executive branch that the prisoner was holding back information, and that the CIA needed to rough him up to get it out of him, the operational order for the torture itself said otherwise. (p.37)

3. After his enhanced interrogation technique sessions, Zubaydah did not produce any intelligence that led to the disruption of any future plot against the United States. His interrogations did produce 91 separate intelligence reports, which did not differ significantly in quality and value from the reports produced before his interrogations. (p.45)

4. President Bush was briefed in October 2002 that Zubaydah was "still withholding critical information" even though his interrogators in the field were telling headquarters that he was compliant and cooperative. (p.47)

5. As late as August 2003, the CIA's top lawyer, Scott Muller, did not know that the Salt Pit site in Afghanistan (Site COBALT in the report) was being used as a detention facility. (p. 57)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

6. Routinely, the CIA interrogators at the black sites assessed the detainees' level of compliance by their "engagement and willingness to answer questions." The headquarters staff, though, judged compliance based on the specific intelligence provided. This is in keeping with their respective roles; the HQ staff has to determine the intelligence that the detainee might provide. But it speaks to a fundamental problem in determining whether it was deemed necessary to deploy the enhanced techniques. (p. 67)

"[I]t is inconceivable to us that al-Nashiri cannot provide us concrete leads.... When we are able to capture other terrorists based on his leads and to thwart future plots based on his reporting, we will have much more confidence that he is, indeed, genuinely cooperative on some level."

7. Poland's relationship with the United States was significantly damaged by the revelations that the CIA had (with the cooperation of the host country) established a black site there. At some point, the U.S. ambassador had to negotiate with the Polish political and national security leadership in order to prevent them from ousting the CIA. (p. 74)

8.The CIA had basically concluded that waterboarding Khalid Sheik Mohammed was making things worse, but continued to use the technique on him for 10 days. (p.88)

9. Mohammed's (fabricated) threat intelligence about follow-up plots within the U.S. caught the attention of the FBI, which wanted to know more. But the CIA basically conspired internally to prevent the FBI from questioning him until he was transferred out of CIA custody.

10. The head of the Renditions and Detentions group, the nominal head of the entire program, admitted in 2003 that, "This difference of opinion between the interrogators and Headquarters as to whether the detainee is 'compliant' is the type of ongoing pressure the interrogation team is exposed to." In 2003. (p. 122)

Marc Ambinder is TheWeek.com's editor-at-large. He is the author, with D.B. Grady, of The Command and Deep State: Inside the Government Secrecy Industry. Marc is also a contributing editor for The Atlantic and GQ. Formerly, he served as White House correspondent for National Journal, chief political consultant for CBS News, and politics editor at The Atlantic. Marc is a 2001 graduate of Harvard. He is married to Michael Park, a corporate strategy consultant, and lives in Los Angeles.

-

Metal-based compounds may be the future of antibiotics

Metal-based compounds may be the future of antibioticsUnder the radar Robots can help develop them

-

Europe’s apples are peppered with toxic pesticides

Europe’s apples are peppered with toxic pesticidesUnder the Radar Campaign groups say existing EU regulations don’t account for risk of ‘cocktail effect’

-

Political cartoons for February 1

Political cartoons for February 1Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include Tom Homan's offer, the Fox News filter, and more

-

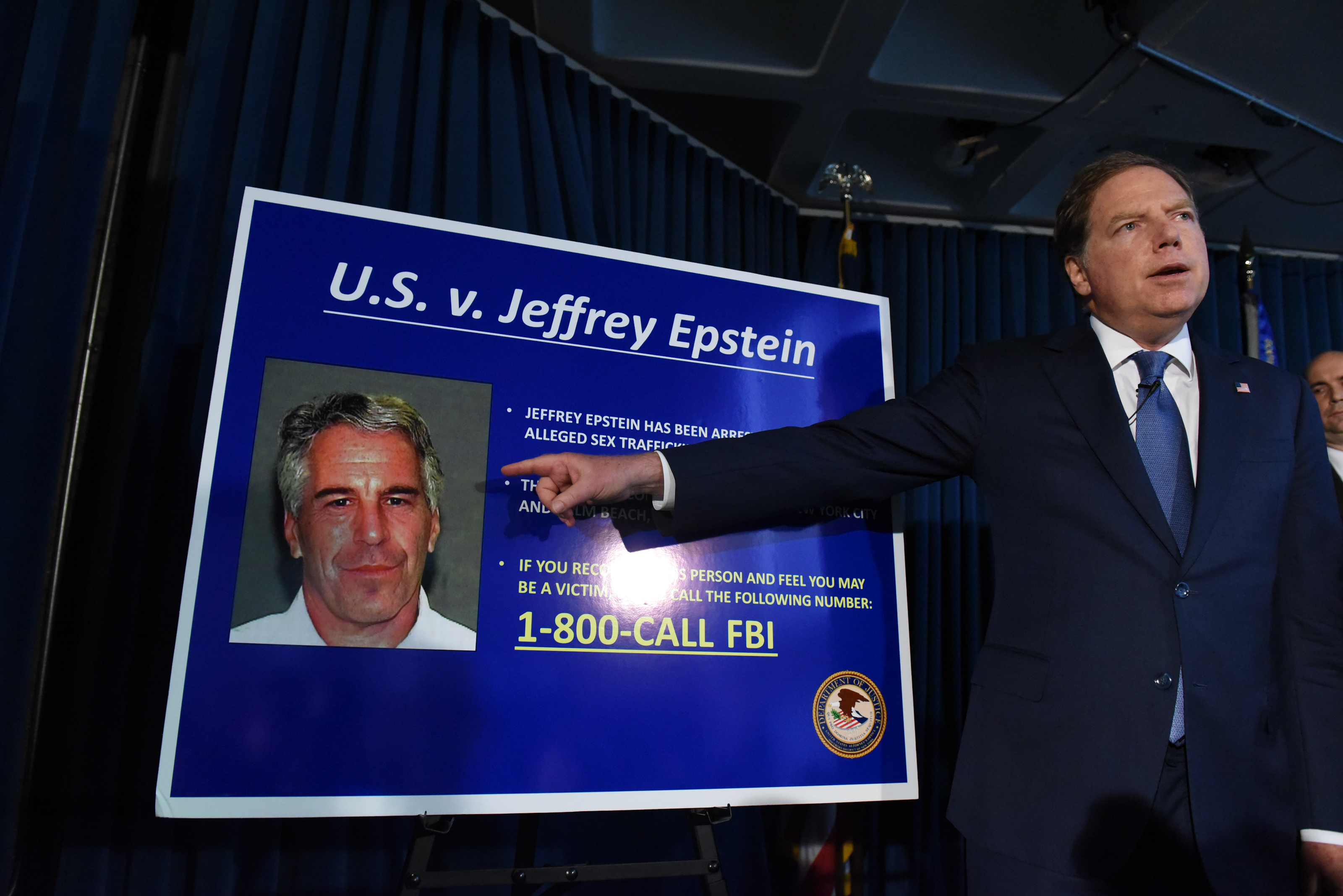

7 lingering questions about Jeffrey Epstein's death

7 lingering questions about Jeffrey Epstein's deathThe Explainer Truth can be as strange as conspiracy theories

-

3 things everyone is getting wrong about the El Paso-Dayton shootings

3 things everyone is getting wrong about the El Paso-Dayton shootingsThe Explainer Mental illness is a red herring — but so is Trump

-

Is it dangerous to lionize the heroes of school shootings?

Is it dangerous to lionize the heroes of school shootings?The Explainer Honoring the children who die saving classmates is laudable — but we should tread carefully

-

The fear we all live with

The fear we all live withThe Explainer What mass shootings have done to the American psyche

-

The sick phenomenon of school shooting contagion

The sick phenomenon of school shooting contagionThe Explainer Mass shootings can spread like a disease, with each massacre inspiring new rampages. Can the cycle of violence be stopped?

-

Why the Parkland conspiracy theories are different

Why the Parkland conspiracy theories are differentThe Explainer They aren't an attempt to make crazy sense of a senseless tragedy. They are a way of saying to the tragedy's victims and survivors: You aren't even worth arguing with.

-

Sex, drugs, and the Summer of Love

Sex, drugs, and the Summer of LoveThe Explainer Fifty years ago this summer, 75,000 young people flocked to San Francisco to "turn on, tune in, drop out"

-

What we know about gun violence may surprise you

What we know about gun violence may surprise youThe Explainer Contradictions abound